Romans walk to the Shrine

The night procession that has been suspended because of the pandemic

Every Saturday night in Rome, in the months from Easter to October, there is a place where a group of believers gathers. They arrive at random in Piazza di Porta Capena, until there are hundreds there. On one side, we you can glimpse the FAO building, with its rationalist air; on the other, the Circus Maximus, experienced in the night as a thickening of darkness, surmounted by the Palatine. It is from here that at midnight, torches in hand, the pilgrimage to what Romans today are most attached, the one that leads from the heart of the eternal city to the Shrine of Divine Love begins.

The journey to the Divine Love begins in the centre and ends in the suburbs. There are more or less 15 kilometers separating the city from the sanctuary. We cross the Appia Antica and Via Ardeatina, passing the catacombs of San Callist and Saint Sebastian. We pass the church of Domine Quo Vadis, where Peter met Jesus, and pray. At the height of the Fosse Ardeatine monument, we gather and remember the victims of the Nazi fury. It is a pilgrimage through history.

Today, the pilgrimage is suspended because of Covid, “But it will resume soon, as soon as the pandemic gives us a break, and it will be even more participatory”, says Sister Paola, who belongs to the Daughters of Divine Love confraternity and has walked that route hundreds of times. The thing that has always struck Sister Paola is the participation, which she defines as “transversal”, made up of people from all backgrounds and sensibilities. Like Chiara Dimuccio, a 39-year-old woman who describes herself as a believer but an “outsider of Catholicism”. She tells us, “The first time I made the pilgrimage was on a Saturday in April, a magical evening in late spring, when you can really breathe eternity in Rome”. Continuing, she says, “You walk slowly and it’s nice to do it in the dark, together with other people who are praying. It’s different from walking alone, because you are part of a collective experience that instills strength”. The pilgrimage takes place at night and usually, at dawn, the sanctuary appears there before their eyes from the Ardeatina, a metaphor for the light that illuminates the night of the soul. It is 5 am and pilgrims can attend the first mass of the day.

The history of the sanctuary founded on the outskirts of the city began in the spring, in 1740, with the story of a miracle. A pilgrim on his way to Rome got lost in the countryside surrounding the city, near Castel di Leva. Just as he was walking by a tower that is home to a fresco of the Virgin and Child, the traveler found himself surrounded by a pack of wild dogs. The beasts advanced towards him menacingly and the man, feeling by now as if all was lost, raised his eyes, crossed the gaze of the frescoed Madonna and invoked her help. It is at that moment that the dogs became tame and so the incredulous pilgrim could escape.

The miraculous episode is communicated by word of mouth across the countryside, and arrived in the city. From then on, that fresco became a destination for veneration and requests for graces, especially for the shepherds and farmers in the Roman countryside. At that time, popular devotion was very strong and so, in the 1740s, the church that still constitutes the original nucleus of the sanctuary was built near Castel di Leva. On Easter Monday, 1745, it was in this church that the fresco of the Virgin with the Child, surmounted by the dove of the Holy Spirit, which is Divine Love, was transferred and placed above the altar.

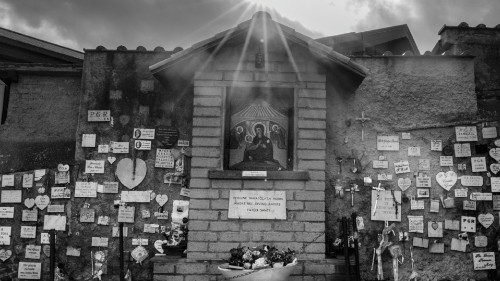

Today, the perimeter of the sanctuary has expanded. The modern one, built in 1999, which is a concrete and stained glass structure that can accommodate thousands of worshippers, has joined the small historic church. The pandemic, with its spacing obligations, has obviously affected the sanctuary as well. Sister Paola explains, “But during the most difficult times, outdoor Masses have been organized, which were a success”. Walking through the sanctuary, the ex-votos are striking; there are thousands of them and they all tell of supplications, graces received and miracles. Sister Paola continues, “Many are from suffering people who entrust themselves to Our Lady, the element of request is strong, because a mother asks for everything”.

The relationship between the Romans and the Madonna del Divino Amore had its turning point during the Second World War. In September 1943 the area of the sanctuary was bombed so the decision was taken to move the icon of the Madonna to the city for its safekeeping. The fresco was first taken to the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina but then -given the huge number of faithful-, subsequently moved to the larger Saint Ignatius of Loyola in Campus Martius. Those were the days when Pope Pius XII invited the Romans to entrust themselves to Our Lady of Divine Love so that the city could be spared from the destruction of war. Between June 4 and 5, the Nazis abandoned Rome, choosing not to make a battlefield of the city. The capital was therefore spared from the bloodiest aspects of the conflict. On June 11, Pope Pius XII celebrated a thanksgiving mass in the Church of Saint Ignatius. Henceforth, Our Lady of Divine Love was given the title of Savior of the City.

In the post-war years, the rector of the Divine Love was Don Umberto Terenzi, a crucial figure for the sanctuary. During this period, thanks to his activism, the seminary of the Oblates of Divine Love and the Congregation of the Daughters of Our Lady of Divine Love were founded. The sanctuary was reborn then as was the rest of the country, explains Emma Fattorini, an historian at La Sapienza University, “From a historical and social point of view, the Divine Love is a symbol of reconstruction, of the energy of the post-war period”. During this same period, the nocturnal pilgrimage was structured in the terms and ways that we know it today, and involving always, more and more women. “In all Marian cults in the post-war period, the presence of women was very strong” continues Emma Fattorini. A pilgrimage became an opportunity to go out, have social relations and gain spaces of freedom, “a sort of new sociality that mitigates traditional female isolation”. According to Fattorini, Marian cults in the post-war period took on an ambivalent value; on the one hand, they transmitted conservative values and also functioned as a vehicle for propaganda, especially in an anti-communist key. On the other hand, however, they nurtured female protagonism. These were the years in which, within the Catholic sphere, the number of catechists and teachers went up, thus increasing the impact of women in the transmission of knowledge.

In the post-war years, a very young seminarian from Altamura, called Michele Pepe, entered the Divine Love and became its first sacristan, and then he became priest and finally a collaborator of the rector, Don Umberto Terenzi. Don Pepe is now 82 years old and has returned to the Divine Love, after spending 40 years as a parish priest in Puglia. When, as a boy, he lived at the Sanctuary, every Saturday night he would accompany Don Umberto to Porta Capena to open the pilgrimage. The first thing we would do was distribute the candles; then we would sing, beginning with the hymn of Our Lady of Divine Love. “We priests stood at the back and took confessions from the beginning to the end of the procession. Today, compared to the past, the quality of the streets has changed, many people carry flashlights, and you certainly do not meet carts and horses anymore. Nevertheless, one thing that has remained constant is that people from all walks of life are there, at the pilgrimage. From the most faithful to sinners, from believers to the curious; those who ask for grace to those who just want to say thank you”.

Despite the fact that the pilgrimage is always very lively, with prayers chanted aloud or diffused by megaphone, there exists along the entire route a quiet aspect, preserved by the night. “The feeling we get is one of anonymity”, says Silvana Cecconi, a believer who has made many processions. “The night shelters the pilgrims; it dilutes the identity of each person.” The journey in the dark gives everyone an intimacy and a new sense of community: “In many cases, I have found myself listening to people with very intimate family problems. It is as if at night they feel welcomed. Everything that they find difficult to talk about during the day, they hand over to the night walk”. For Silvana, “Prayers are useful, but they serve as a background to this special psychological state. It’s a kind of catharsis”.

The night, then. Here is the element that more than any other characterizes this pilgrimage that from the heart of Rome, from the heart of Catholicism, leads towards the dawn of the periphery. “Yes, the night is the main characteristic of Divino Amore”, confirms Chiara Dimuccio, the first pilgrim we asked for this story. “In particular the Roman one, which is a special night. Rome is often described, not always wrongly, also as a cynical, disenchanted city. Therefore, to be amazed, I recommend you make the pilgrimage. See these very different people meet, pray, walk a whole night to reach a shrine outside the city. You have to see and be amazed. It’s worth it”.

by CARMEN VOGANI AND GREGORIO ROMEO

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti