The most beautiful painting of Saint Joseph remained unknown for centuries

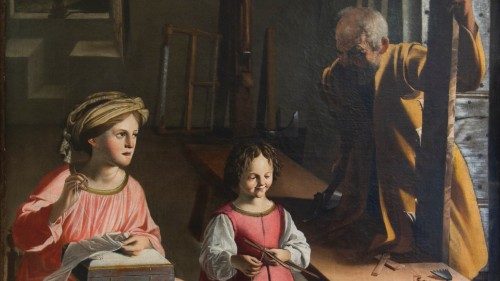

A principled and reserved man, mature, and loving, a solicitous father. This is the Saint Joseph depicted in the beautiful altarpiece of the Santa Maria Assunta church in the small remote village of Serrone, which is today deposited in Foligno’s diocesan capitular museum. Such an important work of art in such a secluded place! A great oil on canvas painting, measuring almost three meters by two, which had had remained unknown for centuries. The painting was discovered about forty years ago, when it was viewed and studied by a handful of experts guided by Bruno Toscano, one of the greatest art historians of our time.

Everyone who saw the painting was enchanted by it; however, they realized upon seeing it that there were no testimonies or historical documents that spoke of who had actually painted it. There was no signature on the work except for a letter “G” marked on a plane behind the standing figure of the tender Baby Jesus. A letter that could identify the author as a mysterious and almost forgotten artist, Giovanni Demostene Ensio. This aristocratic painter was active in the Roman area for Provençal patrons between the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth. A member of the Accademia di San Luca and known only through flattering documentary evidence.

It turned out, in fact, in addition to the marvelous beauty of the painting; the admirable colours were made of precious materials of mineral origin. It is known that maestro Giovanni Demostene Ensio was among the very few at that time to use them, This confirms Toscano’s hypothesis, for it was he who had imagined an unknown painter of French or Flemish origin, working in Italy in the first years of the seventeenth century. The painting represents Saint Joseph’s workshop, in which he is not depicted as a simple artisan, but rather a first rate technician who is working wood destined for a building. In fact, the painter depicts with scientific -truly Flemish-, care the carpenter’s tools, the boards and floors on which the master cabinetmaker is working. In addition, there is the mighty door to the workshop made by Joseph himself, which is ajar to let in the soft morning light. This light illuminates Baby Jesus’ smiling face. His father’s scrupulous, serious, and attentive eyes are tying a piece of white thread from the ball of yarn used by his mother in her sewing, to make a toy in the shape of a cross, a clear premonition of his future Passion. With loving evangelical humility, the painter depicts a myriad of things scattered around the workshop. From the wood shavings on the floor, to the Virgin’s workbox to the clogs abandoned on the ground, all turned by that wise and shrewd man. In addition, it had been he who had designed, built and equipped the large room, including the magnificent mullioned window at the back, making it look more like a cathedral than a workshop. Moreover, it is he who has shaped the family and moral climate that generates both the composed quietness expressed by the young wife absorbed in her thoughts, and the growing awareness of the divine child caught in the magical moment of the first discovery of the family around us, and of the world that will open up before us.

Joseph’s face immersed in the shadows is clearly perceptible. It is in this way that the putative father of the tradition shines forth, signifying the paternal function released from the primary biological factor, which is the exclusive responsibility of the mother.

It is almost as if the painter wanted us to see, through this very human representation of Saint Joseph, how this unfathomable and apparently discriminating principle, does not apply only to him, but actually applies to all human beings, even if our children are not children of God.

Yet, the painter tells us that this is indeed the case. All of us, male or female or whoever, are, as embryos, fetuses and persons, and children of God because the body generated by the mother functions as a result of the fertilization of the egg by the spermatozoon but the life itself that we can call the soul springs from something else that we can call the divine.

by Claudio Strinati

Secretary General of the National Academy of Saint Luke

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti