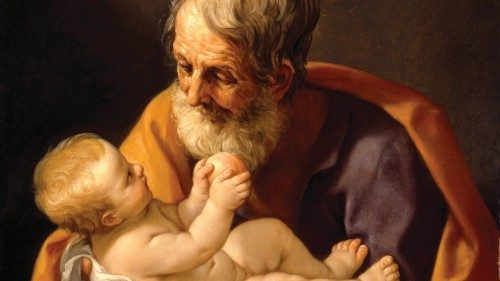

Joseph is probably the saint who more than any other can speak to the people of our time. It is precisely him, of whom the Gospel does not hand down a single word; yet, it is very fruitful to confront ourselves with the symbolic existence of the carpenter of Nazareth.

The fundamental passages of the existential and spiritual story of Joseph are trauma, dream, and action.

Today, we are still immersed in trauma.

The point is that, after the trauma, in the life of Joseph follows the dream and, after the dream, a transformative action. This is the dynamic through which he becomes a father, because fathers become fathers, they are not automatically so just because they happen to be the biological parent.

Joseph's first trauma is Mary’s pregnancy, which for him is no more and no less than a betrayal: a betrayal of his expectations, dreams and hopes.

In the trauma, Joseph falls asleep, that is, he abandons himself, and dreams. In the dream, he meets the Lord’s angel who does not solve his problem, does not change his reality, but simply asks him to look at things from another point of view.

There begins his adventure as a father.

After the dream, and by taking Mary “with him”, Joseph changes his relationship with God and the Law. He was a righteous man, but after the dream, his righteousness is beyond the law. He becomes “righteous” not in the name of the law, but in the name of love. This is not only a singular issue; it is an issue of communities. Joseph is not just a singular symbol; instead, he is a pluralistic symbol, which is why he is so loved by everyone, as the Pope writes in Patris corde.

What does Joseph do as a father?

He helps his son to come into the world, he creates the conditions for his son, that is, life, to come into the world, within the limits imposed on him by the observance of the law, which was that he had to go to Bethlehem for the census imposed by the Roman rulers.

There, another trauma happens, which is that the power, the system, wants the son!

How many analogies here with our own times! Herod is the symbol of power, of the system. Let us not forget that an observant Jew also had to obey the king, not only the priest. Joseph does not hand over his son to the king. Just as before, he had not handed over his beloved Mary to the law of the Torah, which forced him in a perverse way to consign her to public ridicule.

Let us think today about the relationship between technocracies and our children.

A man becomes a father if he does not hand over his son to the system and to the power, and builds the conditions for his son to be emancipated from that power. Are we sure that we are not handing over our children to power, paying for the rescue of the ‘son’ ourselves?

After that second trauma, Joseph takes another step that is necessary for a father. He abandons his religion, his language, his culture, his work, and his traditions so as not to hand over his son to Herod. Are we capable of going on a journey to build the conditions for the mystery and dream of our son to not only come into the world, but to grow too?

There is a third trauma in Joseph’s life. After he had “settled” in Egypt, the signal he received in a dream is that he must return to his home. He thinks about going back to Jerusalem, yet this will become the fourth trauma, the one in the fourth dream, when he is told to go back to Nazareth.

Joseph’s journey is one of transformation of the everyday, a round trip to Nazareth, but when he returns to Nazareth, he has become a father.

Being a father is the human condition for being a son to the fullest.

What we have in common is that we are all sons. I had this experience with my father, when in the last years of his life, he was the son and I was the father who looked after him: he was a father all his life and in the end, he was the son! For a believer this is also in the tradition of faith, for in the end we will all be brothers, only brothers. The father is nothing other than the evolution of the freedom of the person, who makes himself available to be the “you” of the other.

Joseph is a very clear sign of this. The fact that he never speaks in the Gospel is a clear sign of the overcoming of his own “I”. Not of the power of his own self, but of the overcoming of his own self, through being the “you” of Mary and the “you” of Jesus.

How does Joseph’s becoming Father begin? By taking “with” him, not “for” himself, the woman he loved. He passes to the reality of fatherhood through the full acceptance of the reality of the woman he loved.

Being a father is the human condition for being a son to the fullest.

A young man is prepared to be a father when he welcomes and accepts that the reality, which usually hurts us, is almost never, never quite what we expected. Is this not our story? This tells us that the role of the father is a “transitive” role, which is why every father is “the shadow of the father”: one is not a father for life. The pilgrimage of the father, then, is that of a son who, through the experience of being a father, becomes more consciously a son.

This is the last gift that Jesus gives to Joseph, his father, in the Gospel story. Jesus, who was found in the temple after three days, reminds Joseph that he has another Father. Because all fathers are adoptive and foster parents, and no son is the property of his father. The true father is God, or, for non-believers, life, the mystery. Outside of this awareness, there are the perversions of paternity, like the father-tyrant, who uses the power of his role to kill his son, that is, the father-hero, or the perverse father who plays at being an equal with his son.

Joseph gives us the figure of the father-deponent, that is, the father who allows himself to be touched by the authority of God in his relationship with his son, and is at the service of the son, not of his whims but of his mystery.

Unfortunately, the world is full of fathers (and mothers) who put their dreams and expectations on their children, which conditions their freedom, instead of putting themselves at the service of the child’s dream and liberty. Joseph saw nothing of his son in his manifestation as Messiah and Savior. According to what we know from the Gospel, he disappears from Jesus’ life before the beginning of his public life, of his manifestation.

The father does not see his son’s success and is not a father because he measures and enjoys his son’s successes; he is a father because he dreams of his son’s freedom. How far we are from this in a society that only permits children to leave home at 35, in the name of security, burning their youth and the thrill, risk and grace of their freedom. Joseph teaches us that life is risky, it can be unsafe.

Joseph never cursed trauma. His consequential actions show us that he always blessed life, the complicated life that befell him. Therefore, Joseph is righteous, just as Jesus will understand it when he makes justice one of the beatitudes. Justice is not just legality, and it is not simply respecting the rules. Instead, it is the justice of life. Of course, everyone has their own customs and rules, but true justice is also experienced by knowing when one can or must transgress.

Joseph is the fragile one who is not afraid of his own fragility. After all, “do not be afraid”, the angel had told him, as he had told Mary. What do we fear? The disproportion between our fragility and the challenges of life.

Joseph is the symbol of authority, of true authority. His name already says it: “the one who will add”. Joseph is the guardian, but in a great sense, which means more to guard the question than to make the claim to have an answer for every question. Joseph found the answers not by thinking, but by dreaming and by guarding the question. We are as if dominated, in the digital and binary system, by the question-answer dynamic. Joseph's way is another: to guard the question, through silence, by listening, via prayer.

Today, are fathers and mothers capable of sustaining the impossibility of sometimes giving answers to their children's questions? Do they have the courage and patience to safeguard their questions?

Joseph the Monday man. That is, the weekday man.

The “endurance” of the father is not that of a Sunday, but that of a Monday, that is, that of daily life. All this makes Joseph an important accompaniment in our lives. He is important for fathers and for educators. Joseph’s fundamental teaching on education is that educating is not instructing, it is not training, it is not informing. Sometimes to educate uses these things as well. Nevertheless, educating is accompanying the mystery of the child and helping him to come into the world.

Joseph’s other great teaching is about freedom.

Joseph teaches us that freedom is not freedom to choose. He did not choose anything in life. Freedom is being what we are called to be; it is a vocation, both in personal and community terms.

There are questions in life that accompany us to the end. A child is always a question, until the end. In order to safeguard this question in an era of individualism, it is important to be with others, not to close oneself up in the logic of a family closed in on itself.

The page recounting the loss of Jesus and his subsequent discovery is shocking for us: Joseph and Mary had lost Jesus and began to look for him only twenty-four hours later, and found him after three days. A little distressed, it is true, but serene nonetheless. The couple were on a pilgrimage, in a community caravan, they counted on the community. Something that today, unfortunately I would say, is almost unthinkable!

It is not easy to play the role of a father today. What can a father not renounce in order to be able to live his calling to the full, to honor his vocation? In fact, fatherhood is a vocation, not a natural condition, nor a task, nor even less a competence. From a certain point of view, it is even stronger than maternal paternity. Today, paternity is being strongly questioned, but this is not in itself a negative thing.

In the last fifty years, we have experienced a version of fatherhood, which basically, has tried to fight the vision of the father that we have built over the last three thousand years of history. In a machista society, strongly connoted by machismo, the figure of the father that we carried with us was the figure of power. Over the last fifty years this issue has been strongly, but also rightly, contested and fought.

There is nothing to regret about the father who would beat a child, while nobody said anything. Nothing too about the father who oppressed the will of his children with that of his own. Our time has demolished, at least in part and at least in our western culture, the figure of the tyrant father, who at bottom, we must say, was somewhat a projection of a certain image of God. What has emerged is a father who is a bit weaker, a bit disoriented, who struggles to find his own role to play, as if, having removed the sort of absolute power that characterized him in the past, nothing, or almost nothing, remained in the sense of this figure.

We are in a very generative phase from the paternal point of view, precisely because this tyrannical and oppressive figure of the father is dying away; while, on the other hand, what we have managed to give establishes in his place a rather bland, insipid figure.

Along this path of reflection I happened to discover - it would be dishonest of me to say anything to the contrary -, Joseph of Nazareth, who until a few years ago did not mean much to me.

Today, I believe that Joseph brings together, in his adventure as a father, precisely what a father cannot give up.

What can a father not give up?

He cannot renounce love.

Today, we have a very emotional idea of love, a very sentimental idea; I would say a soap opera idea, linked to elements of instantaneousness and emotionality. Love is almost always witnessed by the son and the son is almost never as we thought or wanted him to be, but he is the symbol of love.

A father cannot renounce the custody of love.

Not to make of love what we think, or to make of love what we want. In the end, I insist, we are all children, fathers are only fathers in time, foster fathers, even with respect to our flesh and blood children, or to our deeds that are like children to us; our children, like our deeds, at some point we will have to let them go.

A father cannot give up guarding love through the law and beyond the law; and Joseph teaches us this very well.

Fatherhood requires the responsibility to fulfill the law and to go beyond the law. Justice in human terms is not enough, it will never be enough. There are many moments in the lives of fathers and mothers, in family and marital life, in community life, when it is necessary to transgress the rules in order to preserve the mystery and the dream of the child. I am not talking about adolescent, counter-dependent transgression, but conscious -I would say completely responsible-, transgression.

The other thing that a father cannot give up is to “be there” at the fundamental moments.

To be there when the child is born; to be there - even before that - when he desires to be so; to be there when he has to take care of the child.

Finally, a father cannot give up letting his child go.

I make reference here to the parable of the prodigal son. The paradox of that parable is that the “healthy” son is the one who leaves, who destroys all of his father’s patrimony, who risks death; the less healthy one is the one who stays at home, hidden and crouched behind his father’s rule, but never gambles away his freedom. It is not known how that story ends. When the father goes out for the second time, it is not known whether that son who had always been inside and now, incensed, stubbornly remained outside, has then entered the Father’s party.

The final irrevocable thing for a father is that he cannot give up blessing his own fragility.

Nothing like the truth of the son (but let us not just imagine biological children) lays bare the fragility of the father. The father has little to do with the hero, it has more to do with the servant, who is serenely playing out his experience and testimony with his son; it has less to do with preaching.

The persistent question we always ask ourselves is; how should we do it?

This is always our nagging question, to know how.

Joseph never knew how. This is the question that he kept in his heart all his life, a question that was never expressed, because it was not necessary to generate life.

In Youssef’s life, after every sleep, every dream, there was an awakening, marked by a new path.

Perhaps also for us, “trans-millenarians” like him, who in the first twenty years of this millennium had gone through and went through, from scourges and misfortunes that make us think of the plagues of Egypt. After all, this is the feeling that we feel inside the whisper or the cry of tenacious hope, of a desire to live as new men in a new world.

We began the new millennium with the epoch-making tragedy of the destruction of the Twin Towers in 2001, which was widely viewed as the end of an era. Terrorism has expanded on a global scale, sowing death and fear.

In 2008, we entered into a global economic and financial crisis that is still with us today. In experiencing the collapse of the security placed in the economic power and capitalist regime, which had deluded us with the myth of unhindered and limitless growth and development, to enter a time of instability, stagnation and even negative growth.

In 2020, the Covid19 pandemic forced us to come to terms with the limits of existence and with our own limits. The virus has returned us to our fragility as small creatures in a dark and mysterious world, which we had deluded ourselves into believing we could control and direct exclusively with our will to power. The pandemic has destroyed our illusion of solving everything with the achievements of science and technology; it has brought us into a time of uncertainty and even fear; it has reminded us that “we are all in the same boat” and that no one is singularly saved in this world.

It seems to us that we are living as if we were inside a dream, a nightmare from which we want to awaken. But, how? How are we going to awaken?

Listening to the voices, the words, the experiences of dreams, sleep, trauma and nightmares, like Joseph, and with the courage to get back on our way together, while finding hope again.

Right now, those who do not hope are not free.

We have all been “recluses” and we have understood -at least a little- the condition that prisoners live for years and that the poor live for a lifetime. We have thus discovered that freedom is not only freedom to choose, but also freedom to be what we are, regardless of the conditions in which we live.

We will have a hardening of state forms of control and policing on the one hand and, on the other, the myth of a technocracy experienced almost as if it were a religion, which always seems to assure us of ways out and salvation, will be strengthened. As Charles Péguy taught us, hope is a childlike virtue,

If we must start from today and its depth, we must allow ourselves to be provoked by certain important questions that apply to the task of fathers; and those of educators, which are applicable throughout life.

The first and most important is not to remove our fragility. The pandemic has made us realize that we are all fragile and fragility should not be repaired, but welcomed as the only possibility of a true encounter with others.

The second issue is that we cannot possess hope. Hope is a gift; it does not come from human merit. It is not a business plan, it is not a project, it is a collective movement.

In this passage, we are called to discern what we must save and what we must leave behind. Like Joseph, who at the essential crossroads in his history had the courage to choose to save what was most important - love for Mary and responsibility for Jesus – while letting go of everything else.

by Johnny Dotti

Pedagogist and social entrepreneur

Symposium

Con san Giuseppe oltre il 2021 [With St. Joseph Beyond 2021] is the title of the symposium held Dec. 6-8 at the Generalate of the Oblates of St Joseph in Rome.

Fr. Tullio Locatelli, Superior General Giuseppini del Murialdo will introduce the program; immediately after an intervention by Johnny Dotti entitled With the Adult Faith of St. Joseph, in Filial Abandonment to God, of which a preview is given in this article.

Sister Sara Nicolini, Father Michele Davide Semeraro, Don Cesare Pagazzi, Stefania Colafranceschi, Sister Daniela Del Gaudio, Don Giuseppe De Virgilio and Andrea Riccardi of the Sant’Egidio Community are scheduled to speak over the three days. Concluding reflections will be made by the Saint Joseph Committee.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti