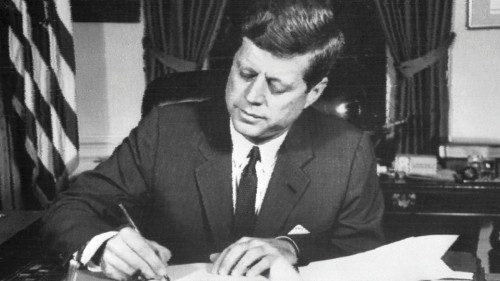

“We pray to God that the sacrifice of John Kennedy may be made to favor the cause he promoted and to help defend the freedom of peoples and peace in the world”. With these moving words, on 23 November 1963, Pope Paul VI recalled the figure of the President of the United States who had been brutally murdered in Dallas the day before. The Pontiff thus emphasized that combination of peace and freedom by commemorating the first Catholic president he had received in the Vatican, only months before his assassination.

Significantly, every year analyses and reflections on the “interrupted presidency” are made as we approach the anniversary of JFK’s death, a sign that despite the fact that almost 60 years have gone by, that political experience still holds a strong fascination and a value that goes beyond the borders of the United States. This year, for example, as we witness a “return” of multilateralism in international relations — albeit not always with exciting results (see the Glasgow Climate Conference) — the contribution John F. Kennedy offered during his thousand days of presidency in favor of a less unipolar international policy, one that was more inclined to dialogue and to multilateral instances, was recalled.

Speaking to L’Osservatore Romano, Agostino Giovagnoli, professor of Contemporary History at the Catholic University of Milan, said “Kennedy’s foreign policy was contradictory, as are often the foreign policies of many countries, especially in contemporary times, when the problems to be faced are many and complex. However, with his image of the New Frontier, he contributed to a climate of hope that is always the best ally of peace. In other words, he partly responded to the aspirations of peoples for international collaboration, something that was very strong in the early 1960s and whose main protagonist was Pope John xxiii , who did much to dissipate the leaden climate of the Cold War, to prevent a ‘hot’ war — for example on the occasion of the Cuban crisis — and to favor a more intense multilateralism, centred on the great international organizations, starting with the UN. Those were the crucial years of decolonization — 1961 was called the ‘year of independence’ — and it seemed that the world would be different with the presence of so many young peoples on the international scene”.

“Kennedy was certainly an internationalist — underlines Ambassador Pasquale Ferrara, professor of Diplomacy and Negotiation at LUISS in Rome — but the sense of this political choice must be clarified. His phrase “let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate” is famous. He was not a pacifist to the bitter end, but he believed in negotiation. He signed the first partial nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, a landmark agreement on arms control in the atomic age. I don’t know if you can call Kennedy a ‘multilateralist’ in today’s meaning of the term. The truth is that there were not many choices then. Today, while maintaining a strong commitment to the UN, the United States is very interested in creating thematic and selective coalitions on major global issues. In the Kennedy years, the fundamental objective of the USA remained that of making the Security Council and the Atlantic Alliance work: two multilateral institutions in their own right”.

One of the fathers of Europe, Jean Monnet, considered Kennedy an American president who was particularly sensitive to the process of European unification. After all, JFK was also the proponent of a closer Atlantic partnership, meeting, as is known, the opposition of Charles De Gaulle, in particular to the United Kingdom’s entry into the European Community. Therefore, what remains today of the Kennedy presidency in the relationship between Washington and Brussels? “Kennedy — Professor Ferrara replies — tried to relaunch the political unity of the West. He went as far as proposing a collective Atlantic nuclear force, associating the European powers, starting from Great Britain, to its management. Today it is curious to note once again the disengagement of England from the EU and a trend towards a bilateralisation of security arrangements (as in the recent agreement between Greece and France). Not to mention the tensions on the eastern borders (Belarus, Ukraine), very different from those of the Cold War, but no less worrying. Kennedy’s legacy suggests that the ‘Europe of nations’ is much more fragile than the Europe of integration, both on the strategic and security level, and on the symbolic one, as a common political space”.

What is certain is that, even after more than half a century, the diplomatic solution to the Cuban crisis remains the highest and most dramatic moment on the international scene of that presidency. Agostino Giovagnoli is convinced of this. “John Kennedy — underlines the historian — made an important contribution to détente in the context of the Cold War. This was especially the case following the Cuban crisis of 1962, when the world was one step away from nuclear war: that danger induced the United States and the Soviet Union to stop before the irreparable and to start a dialogue that led to the dismantling of their respective missile bases in various countries — including Italy — and to develop a negotiation for the containment of nuclear weapons. In 1963, Kennedy visited Berlin — where a Wall that divided the city in two had been built in 1961 — and pronounced the famous phrase: Ich bin ein Berliner (“I am a Berliner”), which on the one hand expressed the full Western solidarity towards Berliners, but on the other hand, it recognized the Wall as a fait accompli that could no longer be questioned”. Kennedy, John xxiii , Khrushchev. The figure of the American president is often compared to the other two protagonists of those years. The themes of peace, dialogue and nuclear disarmament were certainly central to the Kennedy presidency, which also initiated military escalation in Vietnam. Lights and shadows, therefore, while the international appeal of the figure of the president killed in Dallas remains intact. “Kennedy’s appeal — Giovagnoli observes — was largely linked to the aspirations of a Western world that was increasingly more distant from the tragedy of the Second World War, that was archiving the asphyxiating climate of McCarthyist anti-communism, that was experiencing growing prosperity and dreaming of unlimited progress. It seemed possible that modernization and justice could be more and more closely linked”.

A charisma that was also linked to the “open” vision that Kennedy had of the world and international relations, after the horrors of World War II, which he had experienced first-hand as a naval officer stationed in the Pacific. “Compared to Kennedy’s time — Pasquale Ferrara points out — the international context has changed profoundly. But one lesson remains highly relevant. Kennedy said that if we cannot iron out our differences, we can however create a world in which diversity does not necessarily constitute an insurmountable problem. And today the theme of confronting the Western system with alternative systems is at the top of the international agenda”.

Alessandro Gisotti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti