A case of gender violence in the first century

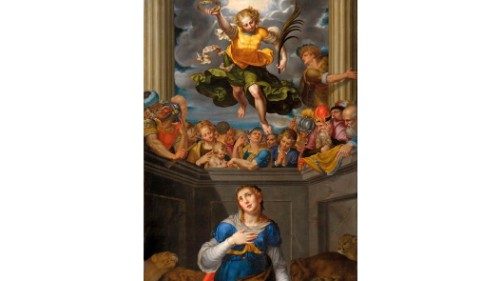

“Sacrilege! Sacrilege!” shouted the women of the city of Antioch as they witnessed the martyrdom of Thecla, disciple of (Saint) Paul of Tarsus. This is one of the crucial moments in the life of a saint who is quite unknown today, but who was greatly venerated at least until the fourth century. Everything we know about her comes from an apocryphal text from the end of the second century, which tells us that a young woman from Iconium, in Asia Minor, was converted by Paul and left her fiancé and family to follow him on his travels. While following the apostle, she was condemned to death twice; the first, at the stake, the other by wild beasts, and on both times she miraculously survived. On the latter occasion, she ended up being self-baptized in the tank of seals that were supposed to kill her, and from then on she began to preach the gospel herself. Her death, which occurred in old age, is shrouded in mystery in the different variants of the apocryphal text.

Thecla therefore had a turbulent personal history, which over the centuries has aroused suspicion, surprise, and sometimes scandal. At the moment when the women of Antioch cried out sacrilege, she had just been let into her second arena, with lionesses, bears, bulls and seals. The condemnation was decreed by none other than Alexander, who made sure the reason was written on a sign reading “guilty of sacrilege”. Guessing her guilt from this one clue, we can deduce that she might have refused to deny Jesus Christ or prostrate herself to the Roman emperor. Instead, we know from history, she publicly rejected and shamed Alexander himself, who had tried to embrace her in the street. She was guilty, in short, of having refused someone’s advances, but it is not so clear why this gesture is likened to a sacrilege. Probably her molester was a high priest of Syria, whom to disobey as a religious authority was an affront to the divinity. Moreover, perhaps, there is also a disrespect here to the social order established for the protection of all, and which regulated relations between men and women. When males are the guardians of females, a woman who rejects a man does not just question him, but an entire value system and culture so precious as to have become sacred. It is a dangerous, sacrilegious act. And yet, from the stands of the Antioch arena, the screaming women are the only ones to catch that misunderstanding: perhaps Thecla is not the profaner but the profaned, and her killing is not a simple injustice but an act of blasphemy against the sacredness she guarded. What is sacred about her that reverses victim and perpetrator?

Thecla and Paul were strangers in Antioch, so the first sacred bond that Alexander disregarded was surely that of hospitality: the stranger owes him nothing, it was he who should have shown her hospitality. However, and above all, his is a real sexual harassment that is evoked in the terms of a desecration, and suggests a certain sacredness of the female body. Accustomed to even recent saints with stories of similar traits (a rejected sexual proposal, insinuations about the victim, the insight that violence is sacrilege) Western Christians take to easily for granted that Thecla was a virgin. Indeed, she was, but the issue goes far beyond moral purity or physical integrity. In first -to second-century Asia Minor, “virgin” means first and foremost “unmarried”, which is a condition outside of all expected patterns. As noted above, Thecla rejected an arranged marriage in order to follow Paul, and joined his travels despite predictable misconceptions. In her, virginity and boldness are tied together. So it is no surprise when, assaulted by Alexander among the people there, she screams, rips his cloak, and throws away his crown. Alexander was annoyed, and as the good manners of the time required, he had already asked Paul for permission to take her with him, and he replied “I don’t know her, she’s not mine”. It seemed to him to have been granted permission after all, if the girl was not Paul’s, she was free. However, the phrase “She is not mine”, from the point of view of faith, says much more: Thecla is not “his” (Paul’s) because she belongs to Christ, and he cannot but recognize her full dignity, autonomy and strength. This young woman acts driven by the freedom that the Lord has given her, and herein lies the fire of her holiness. In spite of himself, Alexander has understood well: Thecla is free. So totally that she even contravenes social expectations.

Thecla’s life is not in defense of anything, not even some physical or moral candor. On the contrary, her story proceeds through scandals, courageous choices, and risks. It has been mentioned: she will even go so far as to baptize herself. If there is something, then, to be kept as sacred in Thecla, if there is something to be protected from all violence, it is not physical weakness or an unblemished body, but the status of freedom, which for Christian communities is always a gift of the Spirit and a sign of the dignity of human beings, of women and of men. “Sacrilege! Sacrilege!” when freedom is threatened and frustrated.

by Alice Bianchi

PhD in Fundamental Theology, Coordinamento Teologhe Italiane [Coordination of Italian Women Theologians].

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti