Debt cancellation, a halt to arms production and the liberalization of patents so that all can have access to vaccines were some of the requests Pope Francis made to world leaders in a video message to participants in the second session of the fourth World Meeting of Popular Movements on Saturday, 16 October. “We are not condemned to repeat or to build a future based on exclusion and inequality, rejection or indifference”, he stressed. The following is a translation of the Holy Father’s words which he delivered in Spanish.

Sisters, brothers, dear social poets!

1. Dear social poets

This is what I like to call you: social poets. Because you are social poets, as you have the ability and the courage to create hope where there appears to be only waste and exclusion. Poetry means creativity, and you create hope. With your hands you know how to shape the dignity of each person, of families and of society as a whole, together with the land, housing, work, care, and community. Thank you, because your dedication speaks with an authority that is capable of proving wrong the silent and often polite postponements to which you have been subjected, or to which so many of our brothers and sisters are subjected. But, thinking of you, I believe that your dedication is above all a proclamation of hope. Seeing you reminds me that we are not condemned to repeat or to build a future based on exclusion and inequality, rejection or indifference; where the culture of privilege is an invisible and unstoppable power; and where exploitation and abuse are customary methods of survival. No! You know how to proclaim this very well. Thank you.

Thank you for the video we have just seen. I have read the reflections from the meeting, the testimonies of what you have lived through in these times of tribulation and anguish, the summary of your proposals and your desires. Thank you. Thank you for including me in the historical process that you are going through, and thank you for sharing with me this fraternal dialogue that seeks to see the great in the small and the small in the great, a dialogue that is born in the peripheries, a dialogue that reaches Rome and in which we may all feel invited and engaged. “If we want to encounter and help one another, we have to dialogue”, (Fratelli Tutti, 198) and how!

You felt that the current situation warranted a new meeting. I felt the same. Even though we never lost contact — I think six years have already passed since the last general meeting — a lot has happened in that time; a lot has changed. These changes mark points of no return, turning points, crossroads in which humanity is called to choose. New moments of encounter, discernment and joint action are needed. Every person, every organisation, every country, and the whole world, needs to look for these moments to reflect, discern and choose, because returning to the previous frameworks would be truly suicidal and, if I may press the point a little, ecocidal and genocidal. I am pressing.

In these months, many things you’ve long been denouncing have become wholly evident. The pandemic has laid bare the social inequalities that afflict our peoples, and has exposed, without asking for permission or making excuses, the heart-breaking situation of many brothers and sisters, the situation that so many post-truth mechanisms have been unable to conceal.

Many things we used to take for granted have collapsed like a house of cards. We have experienced how our way of life can drastically change from one day to the next, preventing us, for example, from seeing our relatives, colleagues and friends. In many countries, governments reacted. They listened to the science and were able to impose limitations to ensure the common good, and they managed, at least for a while, to put the brakes on this “gigantic machine” that works almost automatically, in which peoples and persons are simply cogs (cf. Saint John Paul ii Enc. Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, 22).

We have all suffered the pain of lockdown, but as usual you have had the worst of it. In neighbourhoods without basic infrastructure, (where many of you and millions and millions of people live), it is difficult to stay at home, not only because you do not have everything you need to ensure minimum care and protective measures, but also because your home is the neighbourhood. Migrants, undocumented persons, informal workers without a fixed income were deprived, in many cases, of any state aid and prevented from carrying out their usual tasks, thus exacerbating their already grinding poverty. One of the expressions of this culture of indifference is that this suffering one-third of our world does not seem to be of sufficient interest to the big media and opinion makers. It is not seen. It remains huddled and hidden.

I also want to refer to a silent pandemic that has been afflicting children, teenagers and young people of every social class for years; and I think that during this time of isolation, it has spread further still. It is the stress and chronic anxiety linked to various factors such as hyper-connectivity, disorientation and lack of future prospects, which is worsened without real contact with others -— families, schools, sports centres, parishes -— in other words, it is worsened due to the lack of real contact with friends, because friendship is the form in which love always revives.

It is clear that technology can be a tool for good, and it is a tool for good, which allows for dialogues like this one, and many other things, but it can never replace contact between us, it can never substitute a community in which to be rooted and in which to make our life fruitful.

And speaking of pandemics, we cannot fail to questioning ourselves on the scourge of the food crisis. Despite advances in biotechnology, millions of people have been deprived of food, even though it is available. This year 20 million more people have been dragged down to extreme levels of food insecurity, increasing by [many] millions of people; severe destitution has increased; and the price of food has risen sharply. The numbers relating to hunger are horrific, and I think, for example, of countries like Syria, Haiti, Congo, Senegal, Yemen, South Sudan. But hunger is also being felt in many other poor countries of the world, and not infrequently in the rich world as well. Annual deaths from hunger may exceed those of Covid.1 But this does not make the news. It does not generate empathy.

I want to thank you because you have felt the pain of others as your own. You know how to show the face of true humanity, the humanity that is not built by turning your back on the suffering of those around you, but in the patient, committed and often even painful recognition that the other person is my brother or sister (cf. Lk 10:25-37) and that his or her pain, joy and suffering are also mine (cf. Conc. Ecum. Vat. ii Gaudium et Spes, no. 1). To ignore those who have fallen is to ignore our own humanity that cries out in every brother and sister of ours.

Christians and non-Christians, you have responded to Jesus who, faced with the hungry crowd, said to his disciples: “you give them some thing to eat” (Mt. 14:16). And where there was scarcity, the miracle of the multiplication occurred again in you who struggled tirelessly so that no one would go without bread (cf. Mt 14:13-21). Thank you!

Like the doctors, nurses and health workers in the trenches of healthcare, you have taken your place in the trenches of marginalised neighbourhoods. I am thinking of many, in quotation marks, “martyrs” to this solidarity, about whom I have heard from you. The Lord will take them into account. If all those who, out of love, struggled together against the pandemic could also dream of a new world together, how different things would be! To dream together.

2. The blessed

You are, as I said in the letter I sent you last year,2 a veritable invisible army; you are a fundamental part of that humanity that fights for life against a system of death. In this engagement, I see the Lord who makes himself present in our midst, to give to us his Kingdom as a gift. When Jesus offered us the standard by which we will be judged (cf. Mt 25:31-46), he told us that salvation consists in taking care of the hungry, the sick, prisoners, foreigners; in short, in recognising him and serving him in all suffering humanity. That is why I wish to say to you: “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied” (Mt 5:6), “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Mt 5:9).

We want this beatitude to expand, to permeate and anoint every corner and every space where life is threatened. But it happens to us as people, as communities, as families and even individually, that we have to face situations that paralyse us, where the horizon disappears and bewilderment, fear, powerlessness and injustice seem to take over the present. We also experience resistance to the changes we need and long for, forms of resistance that run deep, that are rooted, that are beyond our strength and decisions. They are what the Social Doctrine of the Church calls “structures of sin”; these too we are called to change, and we cannot overlook them in the moment of thinking of how to act. Personal change is necessary, but it is also indispensable to adjust our socio-economic models so that they have a human face, because many models have lost it. And when I think about these situations, I become persistent in asking questions. And I begin to ask, to ask everyone. And I want to ask everyone in the name of God.

I ask all the great laboratories to release the patents. May they make a gesture of humanity and allow every country, every people, every human being, to have access to the vaccines. There are countries where only three or four per cent of the inhabitants have been vaccinated.

In the name of God, I ask financial groups and international credit institutions to allow poor countries to ensure the basic needs of their people and to cancel those debts that are often contracted against the interests of those same peoples.

In the name of God, I ask the great extractive industries — mining, oil, forestry, real estate, agribusiness — to stop destroying forests, wetlands and mountains, to stop polluting rivers and seas, to stop poisoning food and people.

In the name of God, I ask the great food corporations to stop imposing monopolistic systems of production and distribution that inflate prices and end up withholding bread from the hungry.

In the name of God, I ask arms manufacturers and dealers to completely stop their activity, because it foments violence and war, often in the framework of geopolitical games which cost millions of lives and displacements.

In the name of God, I ask the technology giants to stop exploiting human weakness, people’s vulnerability, for the sake of profits without considering that they increase hate speech, grooming, fake news, conspiracy theories, and political manipulation.

In the name of God, I ask the telecommunications giants to ease access to educational material and the exchange with teachers via the internet so that poor children can access education even under quarantine.

In the name of God, I ask the media to stop the logic of post-truth, disinformation, defamation, slander and the unhealthy attraction to scandal and murk. May they try to contribute to human fraternity and empathy with those who are most deeply damaged.

In the name of God, I call on powerful countries to stop aggression, blockades and unilateral sanctions against any country anywhere on earth. No to neo-colonialism. Conflicts must be resolved in multilateral fora such as the United Nations. We have already seen how unilateral interventions, invasions and occupations end up; even if they are justified by noble motives and fine words.

This system, with its relentless logic of profit, is escaping all human control. It is time to slow the locomotive down, an out-of-control locomotive hurtling us towards the abyss. We still have time.

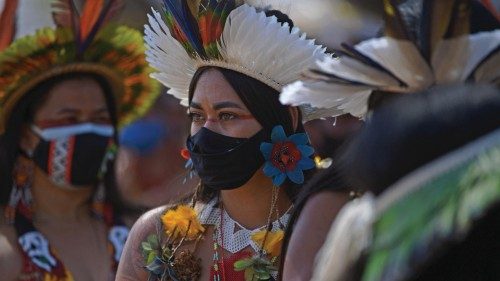

Together with the world’s poor, I wish to ask governments in general, politicians of all parties, to represent their people and to work for the common good. I want to ask them for the courage to look at their own people, to look people in the eye, and the courage to know that the good of a people is much more than a consensus between parties (cf. Evangelii Gaudium, 218). May they guard against listening exclusively to the economic elites, who so often spout superficial ideologies that ignore humanity’s real dilemmas. May they be at the service of the people who demand land, work, housing and good living. This aboriginal “good living” which is not “la dolce vita” or “sweet idleness”, no. This is good human living that puts us in harmony with all humanity, with all creation.

I also want to ask all of us religious leaders never to use the name of God to foment wars or coups. Let us stand by the people, the workers, the humble, and let us fight with them so that integral human development may become a reality. Let us build bridges of love so that the voices of the periphery with their weeping, but also with their singing and joy, provoke not fear but empathy in the rest of society.

And so, I am persistent in asking. It is necessary to confront together the populist discourses of intolerance, xenophobia, and aporophobia, which is hatred of the poor, as well as everything that leads us to indifference, meritocracy and individualism. These narratives have only served to divide our people, and to undermine and thwart our poetic capacity, the capacity to dream together.

3. Let us dream together!

Sisters and brothers, let us dream together. And since I ask all of this with you, together with you, I would like to add some reflections on the future that we have to dream and build. I said reflections, but perhaps I ought to say dreams, because right now our brains and hands are not enough, we also need our hearts and our imagination; we need to dream so that we do not go backwards. We need to use that sublime human faculty which is the imagination, that place where intelligence, intuition, experience and historical memory come together to create, compose, venture and risk. Let us dream together, because it was precisely the dreams of freedom and equality, of justice and dignity, the dreams of fraternity, that improved the world. And I am convinced that through these dreams we will find God’s own dream for all of us, who are his children.

Let us dream together, dream among yourselves, dream with others. Know that you are called to participate in great processes of change, as I said to you in Bolivia: “the future of humanity is in great measure in your own hands, through your ability to organise and carry out creative alternatives” (Discourse to Popular Movements, Santa Cruz de la Serra, 9 July 2015) It is in your hands.

But such things are unattainable, some will say. Yes, but they have the ability to get us going, to put us on a journey. And that is precisely where all your strength lies, all your value. Because you are capable of going beyond the short-sighted self-justifications and human conventions that achieve nothing but continue to justify things as they are. Dream! Dream together. Do not give in to that tough and losing resignation. The tango expresses this well: “Go on and then go on some more! We’ll meet in hell ‘cause that’s what lies in store”! No, no, do not give in to this, please. Dreams are always dangerous for those who defend the status quo because they challenge the paralysis that the egoism of the strong and the conformism of the weak want to impose. And here, there is a kind of pact that was not made, but that is subconscious: the one between the egoism of the strong and the conformism of the weak. But it cannot work like this. Dreams transcend the narrow limits imposed on us and suggest possible new worlds to us. And I am not talking about ignoble fantasies that confuse living well with having fun, which is nothing more than passing the time to fill the void of meaning and thus remain at the mercy of the first available ideology. No, it is not that, but rather dreaming of that good living in harmony with all humanity and creation.

But what is one of the greatest dangers we face today? In the course of my life — I am not 15 years old. I do have some experience — I have managed to learn that you never emerge the same from a crisis. We will not come out of this pandemic crisis the same. We will either emerge better or worse, but not like before. We will never emerge the same. And today together, always together, we have to face this question: “How will we emerge from this crisis? Better or worse”? Of course, we want to come out better, but to do so we have to break the bonds of what is easy and the docile acceptance that “there is no other way”, that “this is the only possible system”; that resignation that destroys us, that leads us to take refuge in “every man for himself”. And thus, we have to dream. It worries me that, while we are still paralysed, there are already projects underway to restore the same socio-economic structure we had before because it is easier. Let us choose the difficult path. Let us come out better.

In Fratelli Tutti, I used the parable of the Good Samaritan as the clearest possible Gospel presentation of this committed choice. A friend told me that the figure of the Good Samaritan is associated by a certain cultural industry with a half-wit. It is the distortion that provokes the depressive hedonism that is meant to neutralise the transformative power that people possess, and in particular young people.

Do you know what comes to mind now when, together with popular movements, I think of the Good Samaritan? Do you know what comes to mind? The protests over the death of George Floyd. It is clear that this type of reaction against social, racial or macho injustice can be manipulated or exploited by political machinations or the sort, but the main thing is that, in that protest against this death, there was the “Collective Samaritan” who is no fool! This movement did not pass by when it saw the injury to human dignity caused by an abuse of power. The popular movements are not only social poets but also “Collective Samaritans”.

In these processes, there are so many young people that I feel hopeful, but there are many other young people who are sad, who perhaps in order to feel something in this world, need to resort to the cheap consolations offered by the consumerist and narcotising system. And others, sad to say, others choose to leave the system altogether. The statistics on youth suicides are not published in their entirety. What you do is very important, but it is also important that you succeed in transmitting to present and future generations the same thing that inflames your hearts. In this you have a dual task or responsibility; like the Good Samaritan, to tend attentively to all those who are stricken along the way, but at the same time, to ensure that many more join in this attitude. The poor and oppressed of the earth deserve it, and our common home demands it of us.

I want to offer some guidelines. The Social Doctrine of the Church does not have all the answers, but it does have some principles that can help this journey to crystallize the answers, and help both Christians and non-Christians. It sometimes surprises me that every time I speak of these principles, some people are astonished, and then the Pope gets labelled with a series of epithets that are used to reduce any reflection to mere discrediting adjectives. It does not anger me, it saddens me. It is part of the post-truth plot that seeks to cancel any humanistic search for an alternative to capitalist globalisation. It is part of the throwaway culture, and it is part of the technocratic paradigm.

The principles I set out are balanced, humane, and Christian, and are compiled in the Compendium drawn up by the then Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace.3 It is a small manual of the Church’s Social Doctrine. And sometimes, when the Popes, be it myself or Benedict, or John Paul ii , say something, there are people who wonder: “Where did he get it from”? It is the traditional Doctrine of the Church. There is a lot of ignorance about this. The principles I expound are in the book, in the fourth chapter. I want to clarify one thing: they are in this Compendium, and this Compendium was commissioned by Saint John Paul ii . I recommend that you read it, and all social, trade union, religious, political and business leaders, read it.

In chapter four of this document, we find principles such as the preferential option for the poor, the universal destination of goods, solidarity, subsidiarity, participation, and the common good. These are practical mediations to put into action the Good News of the Gospel on a social and cultural level. And it saddens me that some brothers of the Church are annoyed when we mention these guidelines that belong to the entire tradition of the Church. But the Pope cannot fail to mention this doctrine, even if it often annoys people, because what is at stake is not the Pope but the Gospel.

And in this context, I would like to briefly reiterate some of the principles we rely on to carry out our mission. I will mention two or three, not more. One is the principle of solidarity. Solidarity not only as a moral virtue but also as a social principle: a principle that seeks to confront unjust systems with the aim of building a culture of solidarity that expresses, the Compendium literally says, “a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good” (n. 193).

Another principle is to stimulate and promote participation and subsidiarity between movements and between peoples, capable of thwarting any authoritarian mindset, any forced collectivism or any state-centric mindset. The common good cannot be used as an excuse to quash private initiative, local identity or community projects. Therefore, these principles promote an economy and politics that recognise the role of popular movements, “the family, groups, associations, local territorial realities; in short, for that aggregate of economic, social, cultural, sports-oriented, recreational, professional and political expressions to which people spontaneously give life and which make it possible for them to achieve effective social growth”. This is from number 185 of the Compendium.

As you see, dear brothers, dear sisters, these are balanced and well-established principles in the Social Doctrine of the Church. With these two principles I believe we can take the next step from dream to action. Because it is time for action.

4. Time for action

People often say to me”: “Father, we agree, but in practical terms, what should we do”? I do not have the answer, therefore, we must dream together and find it together. There are, however, some concrete measures that may allow for significant changes. These measures can be found in your documents, in your speeches, which I have taken very much into account; on which I have reflected and consulted specialists. In past meetings we talked about urban integration, family farming and the popular economy. I would like to add two more to those that still require working together in order to be achieved: the universal wage and the shortening of the workday.

A basic income ( ubi ) or universal salary so that everyone in the world may have access to the most basic necessities of life. It is right to fight for a humane distribution of these resources, and it is up to governments to establish tax and redistribution schemes so that the wealth of one part [of society] is shared fairly, without imposing an unbearable burden, especially on the middle class. Generally, when there are these conflicts, it is the middle class that suffers most. Let us not forget that today’s huge fortunes are the fruit of the work, scientific research and technical innovation of thousands of men and women over generations.

Shortening the workday is another possibility: the minimum income is one, the reduction of the working day is another, and it needs to be explored seriously. In the 19th century, workers laboured 12, 14, 16, hours a day. When they achieved the eight-hour day, nothing collapsed, contrary to what some sectors had predicted. So, I insist, working fewer hours so that more people can have access to the labour market is something we need to explore with some urgency. There cannot be so many people overwhelmed by overwork and so many others overwhelmed by lack of work.

I think these measures are necessary, but of course not sufficient. They do not solve the root problem, nor do they guarantee access to land, housing and work in the quantity and quality that landless farmers, families without secure shelter and precarious workers deserve. Nor will they solve the enormous environmental challenges we face. But I wanted to mention them because they are possible measures and they would mark a positive change in direction.

It is good to know that we are not alone in this. The United Nations has tried to establish some targets through the so-called Sustainable Development Goals ( sdg s), but unfortunately, they are not well known by our peoples and in the peripheries; which reminds us of the importance of sharing and involving everyone in this common quest.

Sisters and brothers, I am convinced that the world can be seen more clearly from the peripheries. We must listen to the peripheries, open the doors to them and allow them to participate. The suffering of the world is better understood alongside those who suffer. In my experience, when people, men and women, have suffered injustice, inequality, abuse of power, deprivations, and xenophobia in their own flesh — in my experience —, I can see that they understand better what others are experiencing and are able to help them realistically to open up paths of hope. How important it is that your voice be heard, represented in all the places where decisions are made, offering it as a cooperation, offering it like a moral certainty of what must be done. Strive to make your voice heard and in those places too, please do not allow yourself to be pigeonholed or corrupted. These are two words that carry great meaning, but I will not talk about them now.

Let us reaffirm the commitment we made in Bolivia: to place the economy at the service of the people in order to build a lasting peace based on social justice and on care for our Common Home. Continue to promote your agenda of land, housing and work. Continue to dream together. And thank you, thank you very much, for letting me dream with you.

Let us ask God to pour out his blessings on our dreams. Let us not lose our hope. Let us remember the promise that Jesus made to his disciples: “I will be with you always,” (cf. Mt 28:20) and remembering it, at this moment of my life, I want to tell you that I will also be with you. The important thing is to realise that He is with you. Thank you.

1 Oxfam, The hunger virus multiplies, 9.7.2021, based on the Global Report on Food Crises (grfc ) of the United Nations World Food Programme, 2021.

2 Letter to the Popular Movements, 12.4.2020.

3 Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, 2004.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti