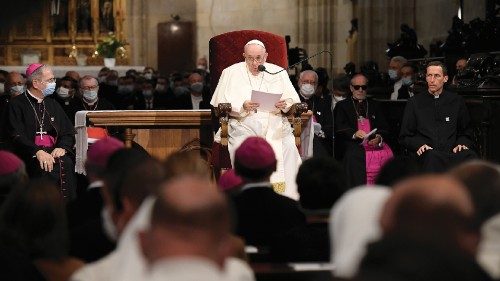

The Holy Father met with Slovakia’s Bishops, Priests, Religious, Seminarians and Catechists in Bratislava’s Saint Martin’s Cathedral on Monday morning, 13 September. The following is the English text of the words he shared with them.

Dear Brother Bishops,

Dear Priests, Religious and Seminarians

Dear Catechists, Sisters and Brothers,

Good morning!

I

am happy to greet all of you, and I am grateful to Archbishop Stanislav Zvolenský for his kind words. Thank you for your invitation to feel at home in your midst. I have come as your brother, so indeed I feel like one of you. I am here to share your journey — this is what a Bishop and a Pope is supposed to do — your questions, and the aspirations and hopes of this Church and this country; in that regard, I just told the President that Slovakia is a poem! Sharing was the style of the first Christian community: they were constant in prayer and they walked together in concord (cf. Acts 1:2-14). They also quarrelled, but they walked together.

This is what we need most of all: a Church that can walk together, that can tread the paths of life holding high the living flame of the Gospel. The Church is not a fortress, a stronghold, a lofty castle, self-sufficient and looking out upon the world below. Here in Bratislava, you have a castle and it is a fine one! The Church, though, is a community that seeks to draw people to Christ with the joy of the Gospel, not a castle! She is the leaven of God’s Kingdom of love and peace in our world. Please, let us not be tempted by worldly trappings and grandeur! The Church must be humble, like Jesus, who stripped himself of everything and made himself poor in order to make us rich (cf. 2 Cor 8:9). That is how he came to dwell among us and to care for our wounded humanity.

How great is the beauty of a humble Church, a Church that does not stand aloof from the world, viewing life with a detached gaze, but lives her life within the world. Living within the world means being willing to share and to understand people’s problems, hopes and expectations. This will help us to escape from our self-absorption, for the centre of the Church is not the Church! When the Church is self-absorbed, she ends up like the woman in the Gospel: bent over, navel-gazing (cf. Lk 13:10-13). The centre of the Church is not herself. We have to leave behind undue concern for ourselves, for our structures, for what society thinks about us. This will only lead us to a “cosmetic theology”… How do we make ourselves look good? Instead, we need to become immersed in the real lives of people and ask ourselves: what are their spiritual needs and expectations? What do they expect from the Church? It is important to try to respond to these questions. For me, three words come to mind.

The first is freedom. Without freedom, there can be no true humanity, for human beings were created free in order to be free. The tragic chapters of your country’s history provide a great lesson: whenever freedom was attacked, violated and suppressed, humanity was disfigured and the tempests of violence, coercion and the elimination of rights rapidly followed.

Freedom is not something achieved automatically, once and for all. No! It is always a process, at times wearying and ever in need of being renewed, something we need to strive for every day. It is not enough to be free outwardly, or in the structures of society, to be authentically free. Freedom demands personal responsibility for our choices, discernment and perseverance. This is indeed wearisome and even frightening. At times, it is easier not to be challenged by concrete situations, to continue doing what we did in the past, without getting too deeply involved, without taking the risk of making a decision. We would rather get along by doing what others — or public opinion or the media — decide for us. This should not be the case. So often times nowadays we do what the media decide we should do. In this way, we lose our freedom. Let us reflect, though, on the history of the people of Israel: they suffered under the tyranny of the Pharaoh, they were slaves and then the Lord set them free. Yet to experience true freedom, not simply freedom from their enemies, they had to cross the desert, to undertake an exhausting journey. Then they began to think: “Weren’t we better off before? At least we had a few onions to eat...” This is the great temptation: better a few onions than the effort and the risk involved in freedom. This is one of our temptations. Yesterday, speaking to ecumenical representatives, I mentioned Dostoyevsky and his “Grand Inquisitor”. Jesus secretly comes back to the earth and the inquisitor reproaches him for having given freedom to men and women. A bit of bread and little else is enough. This temptation is always present, the temptation of the leeks. Better a few leeks and a bit of bread than the effort and the risk involved in freedom. I leave it to you to think about these things.

Sometimes in the Church too this idea can take hold. Better to have everything readily defined, laws to be obeyed, security and uniformity, rather than to be responsible Christians and adults who think, consult their conscience and allow themselves to be challenged. This is the beginning of casuistry, trying to regulate everything. In the spiritual life and in the life of the Church, we can be tempted to seek an ersatz peace that consoles us, rather than the fire of the Gospel that unsettles and transforms us. The safe onions of Egypt prove more comfortable than the uncertainties of the desert. Yet a Church that has no room for the adventure of freedom, even in the spiritual life, risks becoming rigid and self-enclosed. Some people may be used to this. But many others — especially the younger generations — are not attracted by a faith that leaves them no interior freedom. They are not attracted by a Church in which all are supposed to think alike and blindly obey.

Dear friends, do not be afraid to train people for a mature and free relationship with God. This relationship is important. This approach may give the impression that we are diminishing our control, power and authority, yet the Church of Christ does not seek to dominate consciences and occupy spaces, but rather to be a “wellspring” of hope in people’s lives. This is the risk; this is the challenge. I say this above all to bishops and priests, for you are ministering in a country where much has changed quickly and many democratic processes have been launched, but freedom remains fragile. This is especially true where people’s hearts and minds are concerned. For this reason, I encourage you to help set them free from a rigid religiosity. May they be freed from this, and may they continue to grow in freedom. No one should feel overwhelmed. Everyone should discover the freedom of the Gospel by gradually entering into a relationship with God, confident that they can bring their history and personal hurts into his presence without fear or pretence, without feeling the need to protect their own image. You can say to them “I am a sinner”, but say it with sincerity, don’t beat your breast and then keep thinking that you are justified. Freedom. May the proclamation of the Gospel be liberating, never oppressive. And may the Church be a sign of freedom and welcome!

Let me tell you a story of what happened sometime ago. I am sure that no one would ever know where it happened. It is about a letter that a Bishop wrote, complaining about a Nuncio. He said: “For four hundred years we were under the oppression of the Turks, and we suffered a lot. Then for fifty years we were under Communism and we also suffered a lot. But these past seven years with this Nuncio have been worse than the other two!” Sometimes I wonder: How many people could say the same thing about their Bishop or their parish priest? How many? No, without freedom, without paternal love, there is no way forward.

A second word — the first one was freedom — is creativity. You have inherited a great tradition. Your religious heritage was born of the preaching and ministry of the outstanding figures of Saints Cyril and Methodius. They teach us that evangelization is never mere repetition of the past. The joy of the Gospel is always Christ, but the routes that this good news travels through time and history can be different. The routes are all different. Together, Cyril and Methodius traversed this part of the European continent and, burning with passion for the preaching of the Gospel, they even invented a new alphabet for the translation of the Bible, the liturgy and Christian doctrine. They thus became the apostles of the faith’s inculturation in your midst. They invented new languages for handing on the Gospel; they were creative in translating the Christian message; and they drew so close to the history of the peoples they encountered that they learned their language and assimilated their culture. May I ask: Isn’t this what Slovakia also needs today? Isn’t this perhaps the most urgent task facing the Church before the peoples of Europe: finding new “alphabets” to proclaim the faith? We are heirs to a rich Christian tradition, yet for many people today, that tradition is a relic from the past; it no longer speaks to them or affects the way they live their lives. Faced with the loss of the sense of God and of the joy of faith, it is useless to complain, to hide behind a defensive Catholicism, to judge and blame the evil world. No! What we need is the creativity of the Gospel. Let us be attentive. The Gospel is no longer closed; it is open. It is still alive, it is still active, it is still unfolding. Let us think of those people who brought a paralytic to Jesus, but could not get through the front door. They made an opening in the roof and lowered him down from above (cf. Mk 2:1-5). They were creative! Faced with a difficulty they asked “How can we manage this?... Ah, let’s do this…”. Perhaps, faced with a generation that no longer believes, a generation that has lost its sense of faith or that has reduced the faith to mere routine or to more or less acceptable religiosity, let us look for ways to open a hole in the roof; let us be creative. Liberty and creativity… What a fine thing it is when we find new ways, means and languages to proclaim the Gospel! We can use our human creativity; everyone of us has this ability. But the great source of creativity is the Holy Spirit! He is the one who inspires us to be creative. If by our preaching and pastoral care we can no longer enter by the usual way, let us try to open up different spaces, and experiment with other means.

Let me make a little digression here on preaching. Someone told me that in Evangelii Gaudium I talked too much about the homily, because it is one of our problems today. The homily is not a sacrament, as some Protestants claimed, but it is a sacramental! It is not a Lenten sermon, but something different. It is at the heart of the Eucharist. Let us think of the faithful, who have to listen to homilies lasting forty to fifty minutes on topics they do not understand or which do not affect them ... Please, priests and Bishops, prepare your homilies in such a way that they can touch people’s life experiences, and ensure that they are based on the scriptures. A homily, generally, should not go beyond ten minutes, because after eight minutes you lose people’s attention, unless it is really engaging. But it should not last more than ten to fifteen minutes. My professor of homiletics once said that a homily must have internal consistency: an idea, an image and an affect; that people should leave with an idea, an image or something that has moved in their hearts. How simple it is to preach the Gospel! That was how Jesus preached, using as examples the birds, the fields … he used concrete things that people understood. Forgive me for returning to this, but it worries me ... [applause] … Let me be a little naughty: the Sisters, who are victims of our homilies, initiated that applause!

Cyril and Methodius did exactly this, they were open to this new creativity, and they teach us that the Gospel cannot grow unless it is rooted in the culture of a people, its symbols and questions, its words and its very life. As you know, the two brothers met with obstacles and persecution. They were accused of heresy because they had dared to translate the language of the faith. Such is the ideology born of the temptation of uniformity. Evangelization, on the other hand, is a process, a process of inculturation. It is a fruitful seed of newness, the newness of the Spirit who renews all things. The sower sows seed — Jesus tells us — and then goes home and sleeps. He doesn’t get up to see if the seed is growing, if it is sprouting… It is God who gives the growth. Do not control life too much in this regard: let life grow, as Cyril and Methodius did. It is up to us to sow the seed well and to watch over it as fathers, yes. The farmer watches, but he doesn’t go out every day to see how it is growing. If he does this, he kills the plant.

Freedom, creativity, and finally, dialogue. A Church that trains people in interior freedom and responsibility, one able to be creative by plunging into their history and culture, is also a Church capable of engaging in dialogue with the world, with those who confess Christ without being “ours”, with those who are struggling with religion, and even with those who are not believers. It is not a cluster of special people. It dialogues with everyone: believers, those living lives of holiness, those who are lukewarm and those who do not believe. It speaks to everyone. It is a Church that, in the footsteps of Cyril and Methodius, unites and holds together East and West, different traditions and sensibilities. A community that, in proclaiming the Gospel of love, makes it possible for communion, friendship and dialogue to flourish between believers, between the different Christian confessions and between peoples.

Unity, communion and dialogue are always fragile, especially against the backdrop of a painful history that has left its scars. The memory of past injuries can breed resentment, mistrust and even contempt; it can tempt us to barricade ourselves against those who are different. Wounds, however, can always turn into passages, openings that, in imitating the wounds of the Lord, allow God’s mercy to emerge. That grace changes our lives and makes us artisans of peace and reconciliation. You have a proverb: “If someone throws a stone at you, give him bread in return”. This is inspiring. How truly evangelical this is! It is Jesus’ own invitation to break the vicious and destructive cycle of violence by turning the other cheek to those who persecute us, by overcoming evil with good (cf. Rom 12:21). I am always struck by an incident in the history of Cardinal Korec. He was a Jesuit Cardinal, persecuted by the regime, imprisoned, and sentenced to forced labour until he fell ill. When he came to Rome for the Jubilee of the Year 2000, he went to the catacombs and lit a candle for his persecutors, imploring mercy for them. This is the Gospel! It grows in life and in history through humble and patient love.

Dear friends, I thank God for these moments together, and I thank you most heartily for all you do, and for all you are, as well as for what you will do, inspired by this homily, which is also a seed that I am sowing… Let’s see if some plants grow! I encourage you to persevere in your journey in the freedom of the Gospel, in the creativity of faith and in the dialogue that has its source in the mercy of God, who has made us brothers and sisters and calls us to be builders of harmony and peace. I impart to you my cordial blessing and I ask you, please, to pray for me. Thank you!

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti