The challenge of great spiritual friendships between men and women

An elective affinity culturally belongs to a relationship between equals. For this reason important stories of friendships, as well as enmities, have too often been about those between men. Yet, paradoxically, and with a stronger recurrence, elective affinities have bound and bind men and women in the Church. They share the same sensitivity, the same heritage of knowledge, the same social condition and, above all, an identical ecclesial passion.

We know that in the ancient world a friendship between men and women was unthinkable, so much so that the “feminine” term was not even used. The Christian turning point, the common belonging to Christ, the same commitment to his body that is the Church, breaks this taboo. Therefore, that friendship and affinity, also realise a dual inflection that goes beyond the prejudice linked to the culturally irremediable disparity constituted by gender.

The history of the Church therefore runs along the common thread of couples made up of men and women who share the same faith, the same zeal, and the same choice of life. Sometimes, the leadership belongs to the women; and, sometimes they maintain an approach towards their “spiritual” partner that is in keeping with the common feelings and, therefore, emphasize their inadequacy and minority. Often, however, the characteristic of the relationship is a subversion of the hierarchy due to the fact that one of the two is male, a husband, a presbyter, a bishop, in short, someone who is “naturally” appointed to exercise “authority”.

These women stand out and influence - and how they do! - their partners, even fracturing the cultural prejudice, leading them firmly towards a stronger and more radical following of Christ.

What we call “ascetic couples”, where the family bond facilitates the relationship between the sexes, are made up of mother and child, sister and brother, wife and husband, even mother-in-law and son-in-law (this is the curious relationship of Sulpicius Severus and Bassula, mother of his wife who died prematurely). The marriage relationship often evolves in continence, which supports the idea that chastity for the Kingdom is worth much more than the nuptial experience. Nevertheless, we also find - and there are many examples- friendships completely detached from family ties and rooted instead in a common vocation and ecclesial service.

This storyline has grown over time from the apostolic and martyr age to us today. This demonstrates that women have always been present in the Church and that they have always known how to transcend blood relations as well as to weave new ones in the perspective of an unusual friendship, which is beyond prejudice, beyond inequality, beyond the minority in which they have long been inscribed.

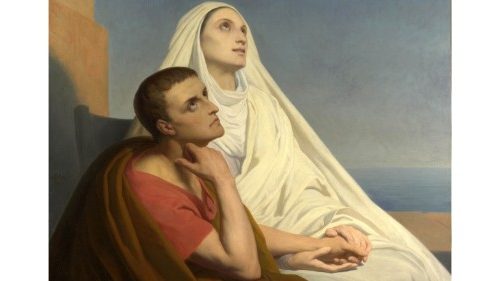

The Passio Perpetuae et Felicitatis shows the catechist Saturus at Perpetua’s side, and the apocryphal Acta Pauli et Teclae places Tecla, an extraordinary female figure, who passionately makes his style and mission her own, side by side to the Apostle. Later, elitist family gatherings show how being bound by blood ties becomes a pretext for a different and intense bond, which generates faith and then introduces the boldness of mystical experience, the most striking case of this is that between Monica and her son, Augustine. In the East, Macrina is a companion and sister in the choice of life and in the dedication to the last of her brothers Basil and Gregory.

Couples such as Melania “the young” and Pinianus, and other similar couples probably developed an ascetic relationship because of the difficulty of procreation that seemed to mark their time. However, truly speaking, the founding anxiety of Melania or that of Paolinus would be unthinkable without the active and complicit presence of those who share their lives.

The same commitment to the understanding of Scripture -including its technical and hermeneutical aspects-, was shared by Jerome and Paula, who followed him to the Holy Land. They continued the discreet service of transcribing and perhaps revising the translation of the Bible we call the Vulgate.

On the other hand, couples such as Chrysostom and Olympia are marked by ministerial commitment. What unites them is their service to the same Church, that of Constantinople, and the dramatic events that occured, which left profound impressions and constitute the keystone of the letters that the former addresses to her.

Then, later in time we find other fraternal couples, for example, Benedict and Scholastica, or other elective couples, like Radegund and Venantius Fortunatus. Henceforth, into the second millennium, there is Francis and Clare; Catherine of Siena and Raymond of Capua; Francis de Sales and Jeanne de Chantal, Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross. Plus, those giants of charity in Louise of Marillac and Vincent de Paul.

In the past century, as proof of a module that has never failed, we find side by side in a concrete shared ideality, the names of Adrienne von Speyr and Hans Urs von Balthasar; Romana Guarnieri and Giuseppe De Luca; Raïssa Oumançoff and Jacques Maritain; Armida Barelli and Agostino Gemelli and many, many others.

The friendly relationship often evolves into passionate and mutual love, which is experienced consciously, while respecting their choice of life. On the contrary, sometimes it is the conjugal relationship that evolves into friendship, giving it a new value that does not lack, however, complicity or mutual affection. The most manifest case of love as an extreme confession that seals the relationship we have is in the Epitaph that Jerome wrote upon the death of Paula, in which he defines himself as “an old man who loves her”. We find a similar sentiment in Francis de Sales who puts an end to his interlocutor’s scruples by telling her not to wonder what the true name of their relationship is; for what matters is that it comes from God and that is enough. A similar experience links Romana Guarnieri and Giuseppe De Luca. In the history of the ecclesial community, the women whose names we have mentioned count indeed. They are founders of innovative life experiences, for example, Macrina, Scholastica, Clare, Jane de Chantal. They are companions in the exercise of a ministry i.e. Paula, Olympia, Adrienne von Speyr, Armida Barelli). Or, they are powerful mystics who create interlocution and following as did and does Catherine of Siena. They are fine interlocutors in intellectual production, while also seen as a ministry or at least as a strong contribution to rethinking and redefining the faith, for example, Vittoria Colonna, Romana Guarnieri, Raïssa Maritain.

Of course, history also gives us the names of defeated women. For these, the love, which then evolves into friendship, has the bitter taste of a maimed relational totality. The most sensational case is that of Eloisa and Abelard; however, we know how much Eloisa outshines her fragile and wounded master/lover/husband, to the point that for too long she was denied the authorship (sic!) of her writings, which were considered too cultured to be attributed to a woman!

Indeed, because a point of contention concerns who wrote what and when to be precise. From the first millennium on, there are no writings by women that attest to these bonds of friendship. Moreover, if Paulinus always places in the incipit of his letters Therasia et Paulinus peccatores, we cannot really know whether he wrote them together with his wife/sister or not. Similarly, we have nothing of the women of the Aventine; no letters have come down to us of Paula or of Jerome’s other interlocutors. We have only the letters of Chrysostom, not those of Olympia to him. Even the tenor of those that have reached us illuminates the stature of the recipients. Instead, the written testimony - and not only the epistolary form -, is present and increases throughout the second millennium.

Joan of Chantal destroyed the letters she addressed to her confessor/father/friend, who in the end says he was her son, or of Clare, Catherine, Vittoria Colonna, Romana Guarnieri, Raïssa Maritain, Armida Barelli, Adrienne von Speyr and others. However, we do have letters and writings, which are very different in style and content, but such as to attest to their authoritative presence, and their passion for the Church.

Their elective affinity and friendship thus testify, with a daring texture, to their unceasing commitment to a Church in which men and women interact, side by side and constantly.

by Cettina Militello

Director of the Women and Christianity Chair at the Marianum Pontifical Theological Faculty

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti