Gender equality read by a writer

After my high school graduation exam, I spent a few days at the Santa Maria Maddalena monastery, in Sant’Agata Feltria, a small town in the hills inland from Rimini.

I was accompanied by a very dear friend, a young Franciscan friar who I had met a few years before. We had maintained a long and precious correspondence that always began with: My dear little sister. It was summer 1990. I was spending three days as a guest of the Poor Clares, sleeping in a room used as a guesthouse and where I ate the meals they offered me on my own. Once a day I would talk behind the grille of the parlor with one of them, and I do not remember well how, but at some distance, I also took part in their prayers. Every now and then, from the window of my room, I would peek into the cloister, where some of them, sitting in the shade and amidst the chirping of the cicadas, were doing their sewing. Every now and then I would go out, take a walk in that enchanting medieval village dominated by the Fregoso Fortress. I would lean out over the valley towards the sea, towards Rimini, where my friends had invited me to join them, and I would think about what they were probably doing, on the beach, the ice cream, the discos, the endless walks along the seafront to watch and be watched by boys.

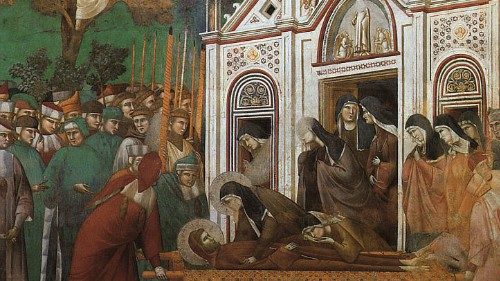

What was I looking for in such solitude? I had no vocation for the cloistered life, but being with the Franciscans had brought me into contact with an idea of poverty, simplicity and equality between men and women that disentangled me from many of the contortions of adolescence. In that bare room I found an essentiality to which I still return from time to time. I had met the Franciscan Order at about the same age as when Saint Clare left her father’s house and joined Saint Francis in 1211, where he was living in a hut at the foot of Assisi. They say that it was friar Rufinus, Clare’s cousin and the first followers of Francis who acted as intermediary between the two of them. In 1209, Clare was sent to buy meat for the friars who were restoring the Porziuncola. Clare’s concern for Francis’ physical health has always moved me, as has the fact that she let him cut her hair, which is a gesture of great intimacy, and abandonment. In their relationship, as in the one they had with their brothers and sisters, attention to the body, to care, was always present.

I can imagine the devoted eighteen year old girl very well. The story goes that as a child she counted pebbles for every prayer she recited and put aside food from her plate for the poor. The person who, when she reached the age to be married, rebelled against a social destiny that had been chosen and signposted, to which she made a breaking gesture. At that age one is not so inclined to compromise; instead, one is attracted by extreme things because these acts give one an identity, and when one does not yet have a place in the world, perhaps only an inner room in which to take refuge. Yet Clare’s escape from the protection and constraints of her aristocratic family - her father was Count Favarone di Offreduccio degli Scifi and her mother, Ortolana Fiumi, was also noble - is not only an act of youthful revolt. Claire knew well what she was about to encounter, “As she heard that Saint Francis had chosen the way of poverty, she decided in her heart to do the same”, she said to her servant Giovanni di Vettuta, at the process of canonization of the saint. Clare remained faithful to poverty, and went on to ask Pope Innocent III for a special privilege in 1216, when the way of life of that group of women, who had installed themselves in San Damiano with her, would have appeared unusual and too much out of the ordinary to the ecclesiastical hierarchies. Her companions there preferred to adapt to the Benedictine norms of female convents with property and income. However, Clare was adamant that she chose not to own anything. She was in love with and convinced of that project of fratres minors et sorores minores, from which the bishop of St John in Acre, James of Vitry, passing through Assisi, had been so impressed that he spoke of it in a long letter. This was 1216, when Francis was attracting more and more followers and Clare, with her first sisters, was probably living in a way not so different from the friars. They were caring for the sick, helping the needy, and living in absolute poverty, in defiance of the conventions of what was allowed to a woman. Even the miracle of the multiplication of bread for her starving sisters tells us how Clare felt equal to any other man in the imitation of Christ.

Clare and Francis belonged to the privileged, in a society where differences were violent. Equally aristocratic and well-to-do, they were each other’s first followers, brothers and sisters, who were sensitive to injustice and convinced that by applying the Gospel they would remedy the inequalities that kept beggars, lepers and the sick away from the palaces in which they themselves had lived, from the respectable streets of the city. There had been a lot of talk in Assisi about the moment when, in front of Bishop Guido, Francis returned money and clothes to his father, who was a very rich merchant, who in vain had cultivated the ambition to become a knight for his son. At that time Claire was a young girl. Over the next five years, she made the decision to follow the example of that young man who, as a dissipater and a pleasure seeker, had proved by example that one could live off one’s own work and alms, without ever accumulating money and goods. Let us try to imagine this, to leave a protected and heated house, provided with choice food, beautiful clothes, jewels, ornaments and servants, to live in uncertainty, in poverty, in service to one’s neighbor. This was poverty in concrete terms. I wondered why in the eyes of Clare and Francis it was so important. The fact is that poverty is revolutionary, it challenges the power among men and the injustices of society. Living barefoot, literally, is very difficult. Nevertheless, how liberating it is to return as creatures, not as historically determined and limited persons. Like stripping off our clothes in a meadow or diving naked into the water. However, it is not always summer or spring, and in a different way Clare and Francis had to come to terms with harsh conditions, enduring illness, immobility, and defeat. The bond between the fratres and the sorores minores was being loosened as much as possible by the hierarchies, so the rule of both had to adapt to obligations that they would not have wanted. Did Clare, ready to leave for Morocco around 1220 to help friars who were being martyred, wish a life of strict seclusion for herself and her sisters? It would not seem so. There were nuns who gave regular service outside the monastery and were dispensed from fasting, from walking barefoot, from the obligation of silence. The cloister was to be a papal imposition. Just as the rule obtained by Francis in 1223 not only severed the link with the sorores, but also saw the loss of importance of poverty, the care of lepers, the peaceful preaching to the infidels that had been capital for the Saint. Their absolute ideals were to a great extent downsized.

Nevertheless, they kept the joy. Now blind, Francis spent a long time in San Damiano, and there, near Clare, he finished composing the Canticle of Creatures, a praise full of love for creation. In the twenty-seven years she lived after him, Clare did not lose the light of their faith, and their form of life. She wrote and succeeded in having a rule of her own approved, which was exceptional for a woman.

In the course of her existence, Clare had visions. The one reported by Sister Filippa, during the process of canonization, gave us a disturbing role reversal. In the vision, Francis nursed Clare at the breast and that milk became gold in her hands: “It seemed to her that it was gold so clear and shiny that she saw herself reflected in it as in a mirror”. This is a very powerful image of their spiritual exchange, which once again passed through a physical act, a corporeality in which male and female are overturned, and seems to me an equally strong sign of their idea of equality and fraternity.

by Alessandra Sarchi

The author

Alessandra Sarchi was born in Reggio Emilia in 1971, and today lives in Bologna. Her publications include the short stories Segni sottili e clandestini [Subtle and Clandestine Signs] (Diabasis 2008) and, for Einaudi Stile Libero, the novels Violazione [Violation] (2012), winner of the Paolo Volponi prize, first work; L’amore normale [The Normal Love] (2014), La notte ha la mia voce [The night has My Voice] (2017), winner of the Mondello and Wondy prizes and Campiello finalist, Il dono di Antonia [Antonia’s Gift] (2020). In 2019, the essay La felicità delle immagini il peso delle parole. Cinque esercizi di lettura su Moravia, Volponi, Pasolini, Calvino, Celati [The Happiness of Images the Weight of Words. Five Reading Exercises on Moravia, Volponi, Pasolini, Calvino, Celati] (Bompiani).

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti