The distorted devotion

Public prosecutor, Marisa Manzini. The Mafia’s use of religious rites

A fugitive mafia boss keeps a portrait of the Virgin Mary in a gold frame in his underground bunker. There is the ‘Ndrangheta widow who prays to the Madonna to reveal the names of her husband's killers so that her children can avenge him. A murderer invokes Mary's blessing before taking up arms.

On the figure of Our Lady, “the mafia’s traps”, as Pope Francis has called them, extend throughout the country, but especially in Calabria. In addition, in Calabria, in the most exposed judicial trenches against the ‘Ndrangheta, Marisa Manzini, a female magistrate from Piedmont, has spent almost the entirety of her thirty years of work as public prosecutor. In September last, the Pontifical International Marian Academy appointed her as one of the experts in the newly created Department of analysis and study of criminal and mafia phenomena.

Manzini, who was also a consultant to the Italian Parliament's commission of enquiry into the mafia, is now deputy prosecutor at the Cosenza court. Women Church World asked her to talk about her experience.

Would you like to make an initial assessment of your work in the Pontifical International Marian Academy (PAMI)?

In these first months, an idea of divulgation has been developed, with the purpose of making known what the mafia is and, as far as I am concerned, the ‘Ndrangheta in particular. We have worked on seminars, which were open to a wide audience. The people present included entrepreneurs, because at this historical moment, with the difficulties created by the pandemic, the capacity of the ‘Ndrangheta to infiltrate the economy is particularly dangerous. Then we started to deal with the mafias’ ability to attain consensus by exploiting the values common to all citizens, which is primarily religious values. We are a Christian, Catholic nation. We know the rules of the Church, and its values. The ‘Ndrangheta and the mafias in general use rites, ceremonies and religious symbols to obtain consensus.

On 15 August 2020, in a letter addressed to the Feast of the Assumption to the Marian Academy, the Pope wrote that it is necessary to “free Our Lady from the clutches of the mafias”. How do you explain the insistence of the criminal associations with the image of Mary?

I have dwelt much - and not only myself - on the reasons for the particular predilection of the ‘Ndrangheta for the figure of the Madonna. I believe that the answer must be sought in the particularity of this criminal association. When compared to the other criminal organisations the ‘Ndrangheta is based on family ties. Within the family, a woman has an important role, for it she who generates the people who will form the ‘Ndrangheta army. She transmits the mafia’s values to her children, while protecting the family nucleus and guaranteeing its unity.

Are analogous tasks attributed to the Madonna?

Yes, I believe that the members of the ‘Ndrangheta identify the Mother of Christ as the One who can protect the nucleus of the family. This is not strictly a personal identification; instead, they unify with it and repair the fractures that are created within that nucleus, resorting also to revenge. This is an important function. It is often held that the women, within the ‘Ndrangheta families, has a secondary role, but this is not the case. Notwithstanding the fact that the organization is masculine and the task of committing the most heinous crimes is entrusted to the men, the woman plays a decisive role in assuring the unity and compactness of the family nucleus.

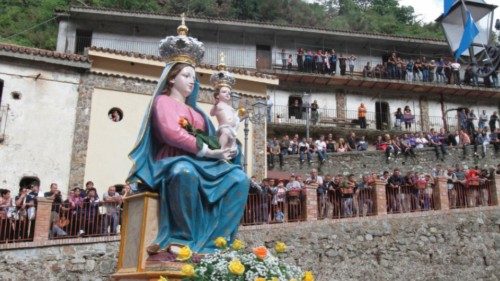

It is known that the ‘Ndrangheta has traditionally celebrated its rites and meetings in the Sanctuary of the Madonna of Polsi, a place it considers sacred. Is this still the case?

Unfortunately, there is a very serious precedent with Don Pino Strangio, rector of the Sanctuary and parish priest of San Luca, the municipality where the Sanctuary is located. He was accused of external complicity in mafia association. In 2017, the bishop of Locri granted his request for the dispensation from office, and took a very clear position, by asking the new rector, Don Tonino Saraco, to return that sacred place to the faithful.

Public ostentation is accompanied by the private display of devotion. In the underground bunker where the Calabrian Boss, Nicolino Grande Aracri, was hiding, a painting was found with a gaudy gold frame depicting the Madonna of Polsi.

Not only was that effigy found. When his house was searched, a Madonna statue and one of St. Michael the Archangel and many holy pictures were also discovered. In a distorted way, this is unacceptable to anyone who knows the Christian religion, but Grande Aracri probably feels he is a religious man. I repeat, this is unacceptable to us, but that is how it is.

This is somewhat like the Graviano mafia brothers who made the sign of the cross before sitting down to eat, even after ordering the murder of the Palermo parish priest Don Pino Puglisi.

I remember a woman from Calabria who struck me. Her name was Giuseppina Iacopetta. Her husband had been killed and, in an interception, I heard her praying to Our Lady to help her children to find the murderers of their father so that the blood of those men could flow at her feet. She really did pray to Our Lady for this, with conviction.

As a Piedmontese, you have spent almost all of your professional experience as a magistrate in Calabria. When did you become aware of the ‘Ndrangheta's claim to use religion to further their consensus?

I was a judicial hearing officer in Turin in 1992, the year of the Mafia massacres. Like all trainees who love criminal law, I felt so caught up in the murder of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino that I wanted to experience the South. On the advice of an older colleague, I chose Calabria. I commenced in Lamezia Terme [central Calabria], and started studying the ‘Ndrangheta phenomenon. I read the justice collaborators’ declarations, I questioned them, and I immediately realized the way in which religion is exploited. Suffice it to say that the insertion into a criminal family happens through a ceremony called “baptism”.

In June 2014, the Pope chose Calabria to pronounce his excommunication against the Mafia. What consequences did those words have, especially in the criminal organisations?

It was a cry that raised awareness. Those words gave a great shock to the Church, to the bishops. The Calabrian Bishops' Conference took a very clear stand against the 'ndranghetista power in their exploitation of religion. Afterwards, however, there have been attempts to condition people through processions. For example, in 2014, the procession carrying the Madonna bowed the figure in front of a boss's house in Oppido Mamertina, a town in the province of Reggio Calabria. On that occasion, the bishop immediately reacted, and prevented the procession from continuing. This was an opportunity to fly in the face of the ‘Ndrangheta and their demands.

You published a book entitled Fai silenzio ca parrasti assai Parrasti: parlasti… [Be quiet and speak a lot Parrasti: talk...], an arrogant invitation to keep quiet addressed by the mafia boss, Pantaleone Mancuso, to a magistrate. How effective are declarations against the ‘Ndrangheta?

I was that magistrate. As a prosecutor in a trial, I had just finished interrogating a collaborator of justice [an informer] when Mancuso started to rail against me. His words were directed at me, but mainly at the territory. Even though he was in 41 bis [a provision that allows the Minister of Justice or the Minister of the Interior to suspend certain prison regulations] and spoke by videoconference, the boss wanted to send a precise message to whoever was listening, which was pay attention, I am still the boss. The mafia and the ‘Ndrangheta are certainly afraid of words. Their law is silence; whoever speaks breaks down the barriers of that world from the inside.

For the first time the Church has beatified a judge and mafia victim, Rosario Livatino. What emotions and reflections did this beatification provoke in you?

I am a believer; everything I have done in my life I have done with the awareness that there are values to which we must refer ourselves. Therefore, Livatino’s beatification, a magistrate who was first and foremost a person of faith, was a great joy for me. For those who carry out my profession, it must represent a light that guides us.

By Bianca Stancanelli

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti