Prophetic rebels: women who dare to change history

Why does prophecy disturb those who exercise it? Moreover, why does it inspire fear in the established authorities? Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that it is not an institutional task managed by the authorities. Instead, it is a free gift from the Spirit that is addressed to everyone, without discrimination of age, sex or social condition. It is a sign of the messianic times, as the prophet Joel announced (Joel 3:1-2), and as the community of the origins had understood well (Acts 2:17-18): “And it will be in the last days, says God, that I will pour out my Spirit on all people; then your sons and your daughters will prophesy, your young men will see visions, and your old men will dream dreams. I will even pour out my Spirit on my servants in those days, both men and women and they will prophesy”. The Spirit, therefore, empowers each one to prophesy, that is, to speak freely and dare to challenge common feeling in the name of a deeper understanding of God's plans.

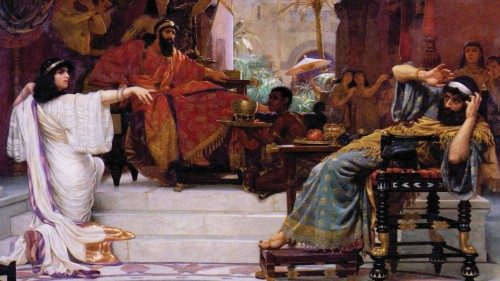

It is not always easy to identify and accept the prophetic voice; after all, doing so is often interpreted as an act of rebellion. This has not always been the case, especially for women whose actions and words have so often been met with opposition because they were seen as unlawfully transgressive. Yet, the Bible is full of stories of women who were the protagonists of their own destiny, and who were able to challenge prejudices and powers. It is women who dared to transgress human laws; for example, Sarah and Rebecca who intervene in the line of descent and the promise by changing its course. Another example are the midwives who saved Moses by contravening the Pharaoh’s unjust measures who sought the death of Hebrew children; and, Esther who helped the people save themselves from certain extermination by defying the commands of the Persian emperor Ahasuerus. These women dared to oppose male authority. More besides, like Miriam who, in her confrontation with Moses, claimed her own prophetic role, or like Judith who cunningly killed the enemy Holofernes, subverting his plans for domination. The list continues, with women who dared to bend the male order in defence of their rights, such as Tamar and Ruth who were able to interpret the Levirate law by securing their female identity and dignity. These, and the women Jesus met and who shattered his certainties, like the Syrophoenician, or the adulteress and the prostitute who challenged his reflection on social hypocrisies are not to be overlooked.

Being bold, transgressive and rebellious is a trait that accompanies the history of women, especially those who have consciously felt invested with a prophetic mission. Prophecy, as we know, is not a charism to be experienced in private; instead, it is a gift that the Spirit bestows to edify, exhort or console the community (1 Cor 12:28). It is a ministerial charism with a marked public and political dimension that guides the group of believers towards the common good (1 Cor 14:4) and, at the same time, it is a spiritual gift, because it descends directly from the Ruach of God. This is why in the history of Christianity we find so many women who have had the strength to speak with freedom, with what the Greeks called parrhesia. Their frankness to express themselves even when standing before the powerful, and often challenging the comfortable arrangements of established power.

In her defense of the privilege of poverty, it was Clare of Assisi’s autonomous awareness that led her to oppose Innocent III with full awareness, stating “I do not wish to be dispensed from the following of Christ under any conditions and never, ever, in eternity” (Legend of Clare, 14). It was Domenica Narducci's pastoral vocation that, in her confrontation with the bishop of Florence, defended her role as a preacher in the early 16th century. She was conscious that the Church needed women and that God calls anyone he wants, including women, to speak prophetically in His name and announce His word.

In the defence of her own revolutionary thought, the indomitable Marguerite Porete did not bend to the Inquisition's order to abjure her faith in a great Church of simple souls who experience their love with God directly. What of the proud Joan of Arc who refused to submit to the judges out of loyalty to the inner voices that had driven her to free France from English rule?

Thoughtful Teresa d'Avila's self-awareness was judged a “restless, wandering, disobedient and contumacious woman” for her determination in full knowledge of the harshness of the times and the unjust limitations imposed on the female gender.

The Mexican nun and poet, Juana Inés de la Cruz, who was forced to abjure before the Inquisition tribunal for having demanded access to knowledge for all those with talent and virtue, called for the right of women to be permitted to study. The list could go on and on, highlighting those women who were regarded with suspicion, marginalised, censured and execrated because they were considered rebellious, disobedient and even heretical wenches by a Church institution that often had to reconsider its own harsh condemnation or simple prejudices.

It is appropriate, however, to recall some of the figures closest to us, who were sensitive interpreters of the signs of the times. We recall the accusations levelled at Maria Montessori for the pedagogical method considered harmful by many Catholics because it undermined the immutable principles of the pedagogy of the time. Although Maria did not take a clear stand against the Catholic hierarchy, but which led her to emigrate, she remained firm in her positive and joyful vision of the human being and in her pedagogical proposal aimed at building a humanity based on relationships of peace and love. Maria Montessori, who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on three occasions, suffered greatly from the misunderstanding on the part of some Catholics who unjustly disavowed her method that placed the child at the centre of her educational project within a prophetic vision of “cosmic renewal”.

The women invited to the Second Vatican Council as auditors were none less combative. Mother Mary Luke Tobin, president of the Conference of Major Superiors of Women's Institutes in the United States was particularly enterprising. To the perplexed council fathers she called for changes in women's religious life, and was not intimidated by the obstructionism of certain cardinals. She always vigorously defended her positions and never failed in her civil commitment even after the conclave, speaking out against wars, in defence of human rights and for a greater appreciation of women's ministries in the Church.

The Mexican, Luz Maria Longoria and her husband José Icaza Manero, presidents of the Christian Family Movement, also dared to do as much. In the presence of astonished bishops and experts, Luz Maria did not hesitate in her opposition of the traditional positions on the reality of marriage, which she described as out of touch with reality. Instead, she proposed a new image of the family based on conjugal love and parental responsibility. After the Council, she and her husband continued to engage in the defense of human rights and to be active in liberation theology, which often pitched them in opposition with the Mexican clergy.

The Spanish Pilar Bellosillo, president of the World Union of Catholic Women's Organisations, who was also an auditor at Vatican II, was not allowed to speak even though she was twice named as spokesperson for the group of auditors. Later, she herself dared to challenge Pope Paul VI and the study commission on ministries by not accepting that the freedom of research and expression of the participants was restricted.

Perhaps it is precisely this anti-dogmatic and anti-authoritarian spirituality that has frightened the ecclesiastical authorities. Perhaps this has led to a difficulty in accepting the freedom of women of faith and in recognising, even if in the diluted times of history, their prophetic voice that anticipates what is to come.

By Adriana Valerio

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti