The Passover of the Samaritans, a people of 800 persons

Iochebed receives us in the living room. She still has her curlers in her hair and is in no hurry, because she can finally rest and dedicate the morning to making herself look beautiful. In the next room, there is a constant coming and going of people. All the men are lined up to wish the High Priest a happy Easter. Abed-El, wearing a long grey suit and a red headdress, has been the spiritual leader of the Samaritans since 2013. He is Iochebed’s father-in-law.

“I carry the name of the mother of Moses, which means Javè is glory”, she tells us with some pride. She knows Hebrew, but speaks mainly Arabic, like all the other inhabitants of Kyriat Luza, a village in the heart of the West Bank on the slopes of Mount Garizim, the sacred mountain of the Samaritans. A people with a glorious biblical past, which today numbers little more than 800, 450 of whom reside in this village, the other half in Holon, a town south of Tel Aviv. They gather together for the most important festivals, which can only be celebrated on Mount Garizim, the religious centre of a community that combines modern life with an archaic faith. They use the TV and the Internet, and study at Israeli universities, but safeguard millenary rituals and traditions.

“I was betrothed to my current husband when I was 14, but he didn’t even speak to me for the following ten years”, says Iochebed, “until one day he showed up with a basket full of potatoes and asked me if I wanted to try them. The following year we got married and we have never had a serious fight in 27 years of marriage. Of course, it is not easy to be a Samaritan woman, for our society puts 80% of the burden on our shoulders. I raised three children and have been working in my husband’s company for 15 years. We produce tahini, and ours is one of the best sesame sauces in the Middle East”. A company owned by the Cohen family, a priestly lineage of the Levi tribe, as confirmed by DNA analysis. The Cohens are one of the four families that make up the community today.

The village synagogue is a modest building, where we enter without shoes and pray on the carpet covering the floor. Men and women together, if they wish, because Samaritans are exempt from the obligation to pray in the Temple.

The Samaritans’ treasure is kept in a rectangular case. This authentic Torah was written on a ram’s skin thirteen years after Moses’ death. The Pentateuch is the only sacred text and is one of the four pillars of the Samaritan religion.

One God, one prophet (Moses), one holy book (the Torah), one holy place, Mount Garizim. The archaeological area of the holy mountain is today an Israeli national park. On the day of the Samaritan Passover, the director is intent on supervising the young girls of the village who, in tight western-style clothes, are busy taking dozens of selfies. Even from rocks that are a little too steep. “The Samaritans have free access to the park, they come on pilgrimage at Easter and on two other feasts,” says the director, Ilan Cohen, a Jew from Jerusalem, “Their holy places are cordoned off as a sign of respect”.

Adam and Eve are said to have met on this mountain, Noah is said to have landed here after the Flood and it is also the site of Isaac’s sacrifice. The excavations in the last century revealed the remains of the temple built here by the Samaritans at the time of Alexander the Great, as an alternative to the one in Jerusalem. This break with the Jewish world has never healed. From the top of the mountain, we can see the two red domes of the orthodox church of Nablus, which houses Jacob’s 40 meter deep well, eight of which are still filled with water. This is the place, according to tradition, where Jesus met the Samaritan woman. This was done in the name of political correctness - the Samaritans were enemies of the Jews - and in complete violation of religious norms. A Jew could neither speak nor drink from a cup made impure by the hands of a Samaritan woman.

On the subject of impurity, two thousand years later things have not changed too much. “We simply continue to follow what the Torah prescribes”, says Nashla, 48, mother to five children, as she chats with her friends in front of the village’s only cafe. “For seven days after the start of my menstrual cycle, no one is allowed to touch me, not even my husband. I have to wear special clothes and eat from separate plates. If I hold my son, then he is impure and I have to bathe him before he can touch his father”.

The period of isolation is prolonged for women who have given birth: forty days when a boy is born and eighty days when a girl arrives. “We are a community and we help each other, but it’s not easy. It is not easy, of course. You can see that the younger ones don’t want more than two children”, concludes Nashla, an English teacher in Nablus, one of the main Palestinian cities with a Muslim majority. When it was called Sichem in Roman times, there were more than a million Samaritans. In the course of history, the number dropped dramatically, due to bloody rebellions and forced conversions to Islam. At the beginning of the 20th century, 150 remained. To ensure their survival, they began to raise large families, but in a society where converts were not accepted, inbreeding created problems. Frequent marriages between first cousins increased the risk of genetic diseases. When Samaritans obtained Israeli passports in the 1990s and had access to the Jewish state’s health facilities, they began to check genetic compatibility before marrying. More recently, mixed marriages have been allowed. The High Priest, the supreme spiritual leader and arbiter even in matrimonial matters, has granted the right to men to marry non-Samaritan women, provided they convert.

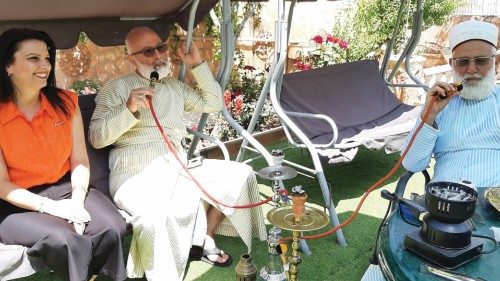

“We can choose who we marry, but it has to be a Samaritan”, says Lubna, sitting in the garden in her bright red silk dress next to her husband smoking a hookah. “Have we come to terms with this fact? I do not say either no or yes, but the fact that there are just a few Samaritan women is a real problem”.

The first to be accepted were Jewish Israelis, who were already familiar with the dictates of the Torah; integration is more difficult for those who come from abroad with a Christian tradition. Today, there are about fifteen of them. Alla was one of the pioneers. A Ukrainian, who crossed the Black Sea to settle on Mount Garizim. She passed the trial period and was accepted by the community. “The impact was hard”, she admits, “but the people helped me. Open and warm”. With Arabic and Hebrew, she has also learned to cook, following religious rules scrupulously. The week before Easter is even more tiring, because apart from bread and meat, you cannot eat anything that is not homemade.

The Easter banquet takes the story back to the first century AD, before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Fires are lit in the ovens around the sacrificial site, where each family brings its sheep. At sunset, the square is full, and everyone is dressed in white. The high priest leads prayers, and when he says, “the people of Israel will be freed from slavery” the animals are killed, cleaned and put to cook on the ashes in the ovens covered with sand. Men, women and children embrace each other and mark their foreheads with the blood of the sacrificed animals. “We celebrate the liberation from slavery in Egypt, just like the Bible says”, a girl tells us. Her blue eyes and blond hair express her belonging to a mixed family. New generations have already begun to press the priests and elders to free them from even the most burdensome aspects of the Torah’s dictates. For example, the protracted isolation after childbirth. If it cannot be shortened, at least we should be allowed to experience it together with other impure women.

By Alessandra Buzzetti

A Journalist. Middle East correspondent for Tv2000 and InBlu2000.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti