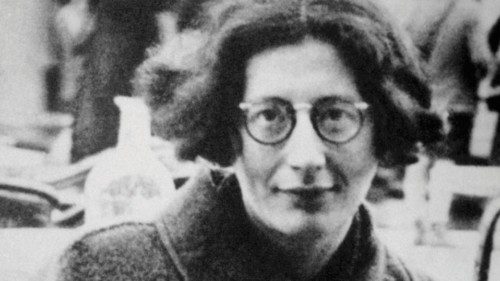

Simone Weil, and her lesson on how to make thought coincide with action

In a photograph, taken in Marseilles in 1941, Simone Weil appears as a figure made up of triangles. There’s one for her face, with the two circles of her glasses protruding beyond the edges, and another, upside down, the triangle of her woolen cape. She has an expression that is difficult to decipher, at the crossroads between investigation and prayer. Throughout her life, apart from a few - intellectuals, political activists, workers, students - who had learned to respect her, she was perceived as an unlikely creature, far from the canons, heedless of the duties that her sex and class required, uncontrollable by the authorities, too rigid for her street companions, and laughable to many.

In Marseille, in Vichy France, a satellite state of the German Reich, she was there with her parents, fleeing Nazi-occupied France. At that time she had already been, as she writes, “taken by God” and in correspondence with Father Perrin, to whom we owe the publication of her letters and her last writings (in Italian Attesa di Dio, obbedire al tempo, edited by J.-M. Perrin, Rusconi 1996).

She was born in Paris in 1909 into an educated, well-to-do and non-religious Jewish family. Because of her father’s work, she and her brother André found themselves travelling a great deal, studying mostly within the family, and being ahead of the regular school students in many subjects. As a child, Simone was aware that the wealthy environment she had been born into was a privilege, and this awareness, the implicit injustice it revealed, had marked her deeply. When she encountered St Francis on her way, she felt his strength. This happened at Santa Maria degli Angeli, in the spring of 1937, during a trip to Italy. While there, she experienced one of what she considered her encounters with God. For the first time in her life, she felt the obligation to kneel.

As recounted in her voluminous biography by her friend Simone Pétrement (Vita di Simone Weil [The Life of Simone Weil], Adelphi 2010), from her first years of teaching Simone Weil refused to heat her room because she could not bear to live in better conditions than the unemployed. She worked in the cold even if the temperature went below zero, and probably this choice, prolonged over time, played its role in the onset of her terrible headaches. She did not give weight to her own suffering, the injustice she suffered did not seem worthy of consideration, but the injustice done to others caused her infinite pain. This may have had something to do with her refusal to be a feminist, with her total disregard for the oppression of women in her expression of admiration for the Greek world, while she dealt with the issue of ancient slavery with lucidity. Simone considered defending herself as intolerable. In her youth she was close to the extreme left, which commenced the day she accompanied a group of unemployed people to demand better living conditions at the commune in Le Puy, where she taught. She became close to the trade union, which brought her into contact with the workers. She was always clear minded about the horrors of the Soviet Union, and even debated with Trotsky, whom she hosted, like so many other known and unknown fugitives, in her parents’ home. She also studied and taught philosophy, science, mathematics and literature.

In her letters to Father Perrin, she recounts the danger she saw in any communal ritual. She writes. “I am naturally very susceptible to influence. If at this moment I had in front of me twenty or so young Germans singing Nazi hymns in chorus, I know that a part of my soul would immediately become Nazi”. She was thirsty for community and knew that any adherence to identity could cause her to lose her clarity; she did not want the Church to attract her in that way. She had a very intense sense of symbols. Simone Pétrement recounts how several times, during demonstrations, she tried to take hold of a red flag and wave it as happily as a little girl.

The experience of working in a factory, which she sought obstinately, would bring to maturity some ideas on the relationship between human beings and machines. In addition, the inhumanity of working-class life which was enslaved to non-human rhythms, to those deprived of the awareness of work and its outcomes, annihilated in the possibility of thought and in which the relationship between those who perform and those who command becomes necessarily authoritarian, blind, and a destructive initiative.

For Simone, who was physically very weak, and tormented by headaches, it was an atrocious experience; but the eradication of every sign of prestige, of every protection, is what she was looking for. This she recognised in the condition of slavery. However, it was only there that benevolence, solidarity -which was not induced by paternalistic or social motives-, exist with their true strength.

In Portugal, in a small fishing village, she attended the feast of a patron saint. There she heard the fishermen’s wives singing “songs that are undoubtedly very old, of a heartbreaking sadness”, she had “the certainty that Christianity is the religion of the slaves par excellence, that the slaves cannot but adhere to it, and I with them”.

From this experience of the factory shop floor, the intolerability of being preserved while others suffer became overwhelming. In her letters to Father Perrin, who indicated to her the path to baptism, she wrote, “When I think of myself concretely, and as an event that could be near, the act that would introduce me into the Church, nothing saddens me more than the thought of separating myself from the immense and unfortunate mass of non-believers”. To save oneself, leaving behind those who are excluded, is beyond her possibilities. With Father Perrin, Simone Weil tackled the question that Thérèse of Lisieux had also raised, that of the question of the salvation of those who remain outside, those who are untouched by faith or preaching. She cannot help but mention with dismay the violence of the crusades and the Inquisition, calling for the Church to take a stand, which would only come with time. Because of the hatred she bore against violence, Simone Weil’s Christianity rejected its Old Testament roots. She found the reading of the Old Testament atrocious, the violence narrated there is completely intolerable for her idea of God. In her thinking about the Old Testament, in her extreme sense of remoteness from Jewish culture as opposed to Greek culture, Simone Weil seemed to suffer from a form of literalism, to lack a sense of history. She seemed to judge the past and every culture based on a very rigid yardstick formed in her present and cast into the future. Weil applies the same inflexible judgement to the Roman civilisation and its empire, which she condemned, with the exception of the much-loved Stoics. In its rigidity, it deserves more understanding on our part, a more welcoming judgment than hers. Who knows where her thoughts would have taken her if she had not died on August 24, 1943, in Ashford, England, of tuberculosis and starvation, after having unsuccessfully tried to play her part, albeit a risky one, in the anti-Nazi war.

The seriousness with which Simone Weil tackled life cannot obscure the comedy with which her skinny and clumsy figure treads the world stage; a kind of female Tramp (she loved Modern Times), who in everyday life goes out with her jumper on backwards. In Spain, where she went to fight, renouncing her pacifism in the name of the anti-fascist battle, she was unable to hold a rifle, and ended up burning herself with a pot of boiling oil and thus was repatriated (she suffered from these wounds for a long time). She loved to laugh which went well with her sense of justice. She enjoyed observing the wrath of the headmasters with whom she worked, the prefects, the hostile journalists, she laughed at them with gusto but without bitterness. There is a humour that she shared with her family too. From Marseilles, she wrote to her brother, who had managed to land in the United States while fleeing the Shoah, “We like to imagine you dipping big buttered canapés in chocolate and shedding big tears thinking of us. You’ll never admit to the big tears, but we’re convinced that you shed them, and we laugh a lot at this idea”.

Simone Weil’s story does not stand up to hagiography, and why should it? Few stories do. But the seriousness without gloom that was her way of being in the world, the radicality with which she chose the side of the excluded, the importance of her thinking when she reasoned about the organisation of work or the duties towards the human person, are moving and necessary, and bring her close to us.

By Carola Susani

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti