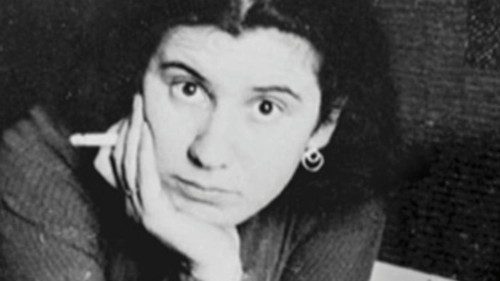

Etty Hillesum, an unprecedented journey even into the abyss of evil

Etty Hillesum was a restless and unsettling woman, who lived outside the box. At a superficial glance, it almost seems as if she wanted to mark out an unprecedented path for her existence, one that was not planned, even appear straggling and aimless, or without perspective. Instead, an “eros”, an urgent primordial force sought to reveal itself, as it urged and swirled within her, for within Etty everything swirled, nothing and no one was ever still, motionless, or calm. In what way did it do so? With what astonishment?

The fact that Etty loved poetry, who was an avid reader and enjoyed music, had a penchant for the Russian language, and was an expert in Law too, is well known. Also clear to us is that she experienced the rush of falling in love, and had relationships with attractive young men, as she herself says, “I broke my body like bread and shared it with men. Why not, they were hungry and had been lacking for so long” [Hillesum E., Diary 1941-1942, complete edition, Adelphi, Milan; henceforth D]. The fact that, through illness, loss, difficulties and anti-Semitic persecution, she managed to grasp something else leaves one astonished and admiring:

A very deep well is within me. And God is in that well. Sometimes I manage to reach it, more often stone and sand cover it: then God is buried. I have to dig him up again (D 97).

In Holland, the persecution of Jews was mounting leading to their deportation to be exterminated. The historical climate in which Etty revealed herself as a writer could not have been more lacking of the (presumed) tranquility the popular imagination considers ideal for those who dedicate themselves to writing. Instead, inspiration for writers like Etty comes from an internal and an external struggle. What the sensitive young girl from Amsterdam lacked she could find inside herself, like a reservoir of feeling, of sensations, of perception.

Etty, the graphomaniac, wrote August 23, 1941 in her monumental Diary,

What I do is hineinhorchen (to listen) (it seems to me that this word is untranslatable). I listen to myself, to others, to the world. I listen very intensely, with my whole being, and I try to imagine the meaning of things. I am always very tense and very attentive, looking for something, but I don’t know what. What I am looking for, of course, is my truth, but I still have no idea what it will look like. I proceed blindly towards a certain goal; I can feel that there is a goal, but where and how I don’t know (D 91).

Weak, unstable and depressed but rich despite believing herself to be poor, she found help in eros. This is not to be understood in terms of unbridled licentiousness, but in terms of the force of impulse which, rooted in the real, in the corporeal, intuitively perceives something else. This is that “beyond” which can be called the Most High Lord by her point of view as a Jewess for her feeling, and non-believer, can be understood in experiencing and letting herself be led by this wave.

A step taken in solitude? A gift of the Spirit descending from above? There may be another valence in Etty’s case: eros that rested its strength on a man she met towards the end of January 1941. This was Julius Philipp Spier, a German Jew refugee in Holland, who was a person of many talents -a banker, a singer, a psychochirologist-, who studied the morphology and classification of hand lines, with an antenna fixed on his head. This is how she describes him:

Piercing clear eyes, the big sensual mouth, the massive almost taurine stature, the free and feather-light movements... Second impression: intelligent greyish eyes, incredibly wise, which for a while, but not for long, diverted my attention from that fleshy mouth (D 4).

Through carnal, sexual love, that subterranean world which required unfolding/ in the spiritual, in the soul, in the spirit, came to the surface and Spier became “the great friend, the midwife of my soul” (D 562).

One should not confuse the Christian lexicon with that of Etty's. Her’s was not a question of conversion to Christianity, for that would have meant betraying herself as a person and her immense legacy that flows through our time.

Etty prays. How does she pray? Whom does she pray to? She penned the answer herself:

When I pray, I never pray for myself, but always for others, or I talk like a madwoman, a child or in a very serious way with the deepest part of me that, I call, for convenience, God (D 523).

The repercussion of this discovery was experienced within. Her health was strengthening, despite the restrictions of war; notwithstanding the drama of Nazi persecution, it was seen in her total boundless involvement in helping others. There too, in the incredible finale, which she experienced with concrete rationality and knowledge of the cause, when she boarded the train for Auschwitz instead of escaping deportation and the cowardly gassing. On August 4, 1941, she said, “It is very difficult to live in harmony with God and with one’s own lower abdomen”. In Wahlverwandschaft, Etty felt akin to Rainer Maria Rilke; for this reason she revealed her own inner murmuring to him:

... even if you are no longer in this world, which is why I would like to write you long letters, you are still alive. To host the other in one’s own inner space and let him or her expand, to keep a place in us where he or she can mature and unfold his or her potential. Even if we do not see each other for many years, to live precisely with the other. Allowing him to persevere in living in us and living with him, for me, is the essential thing. In this way, one continues to move forward with someone, without being overwhelmed by the events of life... when one truly loves, then one must be capable of suffering. Otherwise, love would not be genuine, but only with the centre on oneself; it would be a possessive love... (D 292).

With Spier's guidance, an immense work of cleansing awaited her; she has to sweep up inner waste and fragments in order to be able to arrive at the stille Stunde, the quiet hour. Etty belonged to a very special category of thinking people, who did not ask herself why God allowed the horror of Auschwitz, not even if God suffers, let alone give him up for dead. She made a singular, and very personal leap, in that she wanted to save God. It has to be noticed that idea that we have of God and that for her was that source, that vital reservoir that she had discovered and made her own:

Dear God, these are anxious times. Tonight, for the first time, I am lying in the dark with my eyes burning from scene after scene of human suffering passing before me. I will promise you one thing, God, one very small thing: I will never burden my day with worries about my tomorrow, even if it requires some exercise. Each day is enough for itself. I want to try to help You, God, to restrain my escaping strength, even if I cannot guarantee it in advance. Nevertheless, one thing is becoming clearer and clearer to me: You cannot help us; we must help You to help ourselves. Moreover, that is all we can do these days and all that really matters: we save that little piece of You, God, in ourselves. And perhaps in others too. Alas, there does not seem to be much that You, by Yourself, can do for our circumstances, for our lives. However, I do not hold You responsible for this (D 488-489).

In December 1942, addressing friends, Etty described, with vividness and skill, the environment in which she lived, the transit camp to the extermination camps in the East:

“On the whole there is a great throng, in Westerbork, almost as if around the last wreck of a ship to which too many castaways on the point of drowning are clinging...” (D 620-621).

Always coming to the aid of others, always united but separated from Spier, Etty experienced a crystal clear dimension:

It does not matter whether one is inside or outside the camp, when one has an inner life (D 288-289).

On Tuesday, September 7, 1943, near the village of Glimmen, just before the German border, Etty wrote her last message, a postcard that she dropped from the cattle car that was taking her to Auschwitz:

Christien, opening the Bible at random, I find this: The Lord is my high room. I am sitting on my rucksack, in the middle of a crammed freight car. My father, mother and Mischa are in a few wagons ahead. Finally, this departure has come without warning. Sudden special order for us from The Hague (D 702).

Without illusions, deported on the train of death, but with courageous certainty pulsing in her:

One should want to be a balm for many wounds (D 583).

By Cristiana Dobner

Discalced Carmelite, prioress of the monastery of Santa Maria del Monte Carmelo in Concenedo di Barzio (Lecco). Theologian, writer and translator.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti