Do not insist on grieving, think of the living: This is what we are asked.

However, is there not a risk of breaking the thread with the second life?

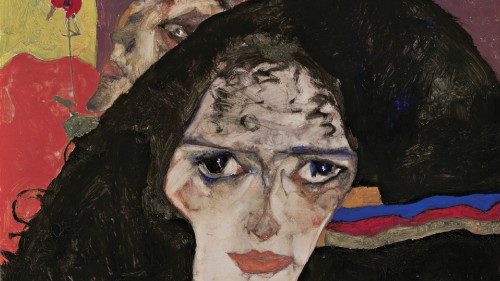

Grieving, returning to normal life. This is what we are asked when death enters our lives. We are asked to distract ourselves, to move on, not to look back, and not think of those who we have left behind. Those who have left do not come back, and we have a duty to go on living, and there is only one-way to do this, and that is to put aside the past. Grief and memory can be accepted, of course, but only for a few days. Mourning - the social behavior that signals the passing of death - is useless and retrograde, just a set of rituals that modernity has rejected. Akin to an old-fashioned dress, or a black-and-white film. We do not say it, but we think it is a waste of time. The insistence on pain is madness.

In recent years, it is happening to me more and more often, due to my age, those who pass away are happening in my life more often. Moreover, I find myself in hurried public and private funeral ceremonies, and think of the rites of my childhood.

These are precise memories from a time long gone.

The women who washed and dressed the dead. The mixed smell of flowers, candles and vinegar. I still do not know why the dead were washed with vinegar.

The bed made up with the best sheets that awaited them for the last time. The long vigils beside the deceased. The care so as not to leave the person alone.

Then the funerals with orphans and nuns in the front row, the women dressed in black, the men with dark armbands, music playing for the rich. The church ceremony, the priest’s words, just the priest’s, the music, the pain blended with prayer.

The mourning begins with precise rituals and timings. A year, even two, of wearing black clothes for the closest relatives; followed by half mourning, when some hint of white was allowed. Any amusement was prohibited, holidays were abolished, and visits reduced to those closest and dearest.

Those who died remained present, they were talked about, and he or she continued to talk to us, filling our conversations, populating our dreams. Their portrait with a candle, and flowers placed in a central part of the house. I remember two neighbours who upon returning home waved to the deceased, and greeted them in the now empty rooms.

I once said, “There is no one there,” I must have been no more than five years old at the time. They replied, “The souls of the dead are there”.

The souls continued to remain close to their loved ones. They were asked for advice, prayed for and hoped for. In the other realm, they had greater powers and continued to keep watch. The dialogue could continue, and death did not interrupt it, and life did not hinder the memory, but rather it could be understood, and nurtured it. The souls of the dead could be frightening, because they were strict and controlled the living, but at the same time they protected, they guaranteed contact with a world to which we would all one day go.

Grandma visited Grandpa at the cemetery twice a week, on Thursdays and Sundays. I often accompanied her, even though I had never met my grandfather. First, we stopped to buy flowers, and when we arrived at the little family chapel, she would clean everything up and arrange them, while I was in charge of fetching water. Then when everything was shiny, Grandma would talk to Grandpa, tell him the latest family news, and then say goodbye and we would leave. This happened twice a week for as long as it was possible for her, and for me, being the one chosen to accompany her, was a privilege.

Today, I understand why. I used to participate in the mourning ritual and this forced me to enter the world of adults. In the world of the women who had assisted, watched over and then protected the memory and life after the death of their loved ones.

Later, I came to think about the protagonists of the end-of-life rite, and why they were all women. The men were there - the priest, the gravediggers, and the black sash wearers during the funeral - but they disappeared soon after, drawn into their business, their work, the world that did not stop. Grief was not a male affair. Women had the task of not forgetting, of linking the present with the past, of not depriving the future of what had been. They again had the task of giving life, a second life, that of remembrance and memory, of love that does not end with death that finds new forms to remain and continue to exist.

I am not nostalgic for those times; for I do not think it was good back then. I cannot help but see, even in the division of time, in the management of death, the nefarious separation of roles that has so marked the female condition. In addition, I cannot beatify the tasks of women, their dedication to care, even to that of the dead.

Today, I can see clearly what has happened since the rites of death were abolished, for mourning was considered useless and the caring for those who are no longer there delegated to “specialists”. As people generally die in hospital, their pain, illness and care are managed from outside and women, like men, are merely spectators of inevitable events.

What has happened is that the cult of memory, the closeness with those who are no longer there, the dialogue that continues even when breathing has stopped, have been reduced or abolished. They have come to be considered unnecessary sentimental digressions that take time away from the lives of those left behind. The culture of our progressive and advanced countries -which is experiencing a paradox and a contradiction-, demands this of us. While public discourse invites us to remember and the study of history and the refusal to forget are a civic duty, celebrated by institutions and taught in schools, the death of individuals is to be erased and set aside.

Since the link between women and death has been severed - the care of death - the thread with the second life, that of memory and remembrance, has also been torn, and the time of mourning has been removed for its uselessness.

However, is this really a good thing, is it good for those who are left behind, the sudden departure of those who are no longer with us? Moreover, is it really madness for those who want to maintain the suffering in order not to abandon the memory? Is it more preferable to forget rather than suffer? Is this what we must teach our children? Is this what we must move towards as we imagine the future? On the other hand, do we have to -both women and men-, rebuild a culture of mourning, of accepting the inevitable, of pain and the mystery of death as an opportunity to rediscover each other and ourselves? To give a second life to those who are gone and to hope to receive it as a gift when it is our turn? A poet once said, “Only he who leaves no legacy of affection little joy have an urn”. And, he was right.

by Ritanna Armeni

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti