At a time when the pandemic is imposing isolation and accentuating loneliness, these two related miracles are so important today.

Birth is woman. The miracle of birth cannot take place without a woman’s body becoming a welcoming womb and guardian, right up to the moment of birth.

At crucial moments, the woman giving birth is helped by other women be they a mother, sisters, friends, or neighbours. The midwife is a woman. Femininity is generative and maieutic. The beginning of life is made possible, encouraged, accompanied by the womb, hands, arms, voices, songs, prayers, gestures, female care.

This is true in every culture and time.

For believers, the very story of salvation begins like this. From an incarnation, from passing through the narrow door of a woman’s body and from the tenderness of a gentle, welcoming touch.

Perhaps for the same reason, as the saying on an island in Guinea Bissau goes, “the things of death are also the things of women”.

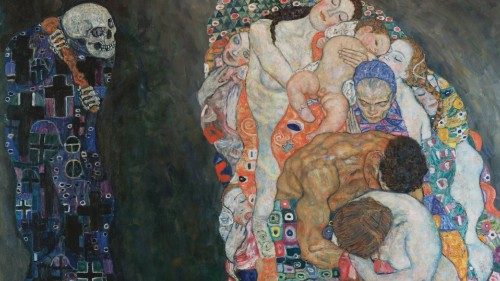

In the history of salvation, too, it is women who take care of Jesus as he goes to die -Veronica wiping his face on the road to Calvary-, who faithfully accompany him as he passes by, and the three Marys at the foot of the cross, who weep over his dead body. This we see in the rich iconography of the mourning over the dead Christ, from Giotto to Mantegna, who witness the deposition in the tomb; and, who receive the announcement of the resurrection from the angel.

Women bear witness to and proclaim the miracle of salvation, which is for us all, our birth, death, and resurrection as steps on a single path, where death is the bridge between mortal life, in time, and immortal life, in eternity.

It is to women that this mystery is given; it is them who bear witness to it with their capacity to generate and let go, entrusting the fruit of their womb to life. A theological dimension that stitches together the body and the breath of the spirit, the earth and the sky, the beginning, the end and the eternal in one great picture of salvation.

There is still much to be questioned about this mystery.

Passages (no longer) accompanied

In every culture, the mystery of death and transit has always been at the centre of a collective cultural elaboration. However, since modernity, which has dismissed much of this culture as infantilism and superstition, the framework of meaning within which to interpret and rework this ineluctable dimension of existence has disappeared. As the German sociologist Norbert Elias wrote in The Loneliness of the Dying, among others, in societies that call themselves advanced, people fall ill, grow old and die increasingly often alone. These people are isolated from the community, in specialised facilities that medicalise the end of existence and remove the sick and the elderly from the gaze of others, leaving them at the mercy of anguish.

A condition that the advent of Covid has further radicalised.

It is the ritual dimension that has disappeared, which is that particular form of collective social action whose etymology is rooted in the idea of order, correspondence and bond. This ritual aspect produces meaning by linking heaven and earth, the immanent and the transcendent, and within this alliance, it creates the conditions for a deeper bond between people. It is a language that speaks through sensitive elements i.e. the body, or symbols, where everything means itself and more than itself; a sequence of gestures that connects the community and the generations, in a shared history that persists beyond what passes.

Just as one comes into the world thanks to others and with others, so too death must be accompanied; moreover, it is women who preside over these moments of passage and transmutation.

Funeral rites are typically rites of passage and accompanying transit, characterized by the triple structure of separation/marginalization/aggregation. The vigil over the deceased is to work though the separation, the ritual accompanying the burial, the prayers for the souls of the dead who, from their new condition, can watch over the living. These all fit into a scheme that organizes social life at its most crucial moments. In addition, there are also all the customs that strengthen the link between the world of the dead and that of the living. These include the custom in many regions of Italy of “setting the table for the dead” on the November days dedicated to their memory, cooking their favourite dishes and exchanging memories, to keep their presence alive between generations.

In this way, death, which is also an abyss and a mystery, can be made part of our everyday life as a window of meaning. The invitation of the poet Mariangela Gualtieri is to “make death familiar with our habitation of it”.

The rites are languages for inhabiting death, for making it familiar, for transforming the laceration of death into a new bond between heaven and earth, which strengthens the bond between those who remain.

It is of this mysterious but meaningful link that Cristina Campo speaks of in one of her poems: “I never pray for the dead, I pray to the dead. The infinite wisdom and clemency of their faces - how can we think that they still need us? To every friend who leaves I speak of a friend who stays; to that infinite kindness without wrinkles I remember a face from down here, tortured, swaying”.

The process of secularisation has crumbled the frame of meaning linking death to resurrection, while individualisation has left us alone in facing the moment of detachment, which simply becomes an end, a nihilisation, and a dissolution of what has been.

To trivialise the ritual, to empty it out, or to ridicule it means to deprive the individual of a collective support and a horizon of meaning, leaving us alone with ourselves, crushed by anguish and mute, without hope in the face of death.

The deleting of the ritual also prevents us from seeing that life is not real life if it claims to remove death as an uncomfortable presence on its horizon. Instead, it only becomes one if we assume it as part of ourselves.

Two miracles, one paradox

“The living beings” are also called “mortals”. Our existence unfolds between the moment of birth and that of death. As St Francis wrote, “Our sister bodily death from which no living person can escape”.

Birth and death, are two miracles which are linked. Two signs that continue to arouse wonder, amazement, and dismay. They are two unprecedented breaches in the repetition of our existence, which irreversibly transform it; two symbols, two moments of a greater history, full of mystery and hope for all.

If there were no link, not even the miracle of the transformation of death into life, which we see happening all around us if we learn to recognise it, would be possible. For example, parents who from the loss of a child begin a journey of rebirth by doing something for others; traumas that instead of destroying a person open up an unprecedented possibility of existence; having lost everything, lives that inaugurate a new step and that open up a horizon of fullness.

We must not therefore think of life and death as the opposite of each other. Their link is paradoxical, it does not respond to logic and the principle of non-contradiction. The Gospel tells us this (he who is willing to lose his life will find it) and our times, which are so full of pain and death, suffering and anguish, also show us this. However, we also see a great deal of humanity flourish, a great capacity for resilience nourished by care and dedication to the sick and the most fragile. Someone has lost their life, but paradoxically they have saved it, they have made it whole, they have given it a meaning that does not end with the death of the body but remains as a promise of fullness in which others can trust. A sign that nourishes life.

Paradoxically, this is the time when death cannot be removed, when every day information starts with data on contagions and deaths, is a time of revelation of a truth about life. Etty Hillesum wrote in her Diary, “I know, now, that life and death are significantly linked”. Two faces of the same reality that unites us all in a common destiny.

If we conceive of death as a sister rather than an enemy, our view of life changes.

If the two are linked, and if the link is not one of exclusion but of paradoxical union, a reversal of perspective becomes possible, especially when death makes itself felt more strongly - as it is at this moment.

Meanwhile, from the point of view of death, life does not appear as a given but as a gift. As the condition of transformation, of that dynamism that passes through death to affirm life (only the grain that dies bears fruit). As Wolfgang Goethe wrote, “Die and become!”. In addition, as Rainer Maria Rilke “The great death that each one has within him /Is the fruit around which everything changes”.

While considering death from the point of view of life generates anguish, considering life from the perspective of death makes us see more life, gives a new breadth to our pale and dull existence which qall too often is crushed on a horizon of urgency and immanence. As in Patrizia Valduga’s verses, “Lord, give to each his death, from the whole reversed by life; but give us life before death, in this death that we call life”.

There is a mortal life and there is a vital death. Separating them and removing death -contrary to what we have believed-, is not good for life.

The Jesuit scientist and philosopher Teilhard De Chardin wrote, “Death is charged with practising the necessary openness in our innermost selves”.

Etty Hillesum also recognises this in her diary, when she says “The possibility of death has become perfectly integrated into my life; it is as if it is made wider by that, by facing and accepting the end as part of oneself. It almost seems like a paradox: if you exclude death you never have a complete life; and if you accept it into your life, it expands and enriches it”.

Now that death cannot be excluded, that our delusions of omnipotence have suffered a setback, that we have realised that we are all interconnected (it took a virus to prove it) and that we need to give meaning, together, to this time, perhaps we can take a new look at life. And learn the movement that Cristina Campo suggests in one of her verses, “With a light heart, with light hands, life to take, life to leave”.

by Chiara Giaccardi

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti