...of women has marked gender relations in the West

To what extent has this also happened in the Church? An historical theologian’s analysis

At the end of the 1300s, a concerned confessor, Jean le Graveur, set about transcribing the visions of Erminia of Reims, a young widow who was thought to have gone “out of her mind”. From these imaginative dreams, the woman who emerged wanted to escape the confines of her home and travel the world. In addition, she hoped to remarry and wished to free herself from her confessor’s strict control in order to have a freer dialogue with God. The study of this ancient manuscript, which has come down to us with the commentary of the refined attention of historian André Vauchez, highlight the extent of men’s fear of any manifestation of female autonomy in the past. In short, the difficulty to accept spheres of freedom for women, in fact, Erminia's dreams were judged the result of demonic temptations.

Fear of women has been, and still is in many contexts, one of the great fears of the West. Is it also in the Church? And if it is, to what extent?

At the time of the Second Vatican Council, and thereafter, the Magisterium has shown new attention and sensitivity towards women. Their dignity has been defended and valued for what John Paul II called the feminine genius, but much remains to be done to overcome resistance and prejudice. Pope Francis himself recently stated that “we must move forward to include women in council positions, even in government, without fear”, and reading between the lines, this shows how many difficulties still exist in accepting a full, authoritative and responsible participation of women in the life of the Church. This still persists, but of what does this fear of women consist? A look to the past can perhaps help us understand the deep-seated reasons for this primary defensive emotion that men express by activating practices of denial or marginalisation. Above all, because this was not always the case.

The early community

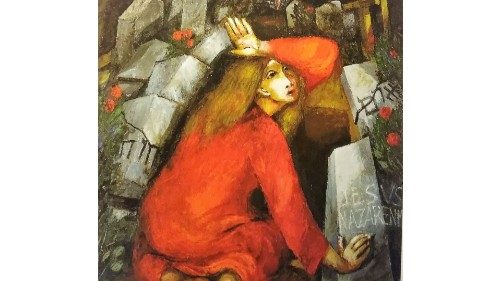

Jesus was certainly not afraid of women. On the contrary, women’s most radical liberation began with him. In fact, he entered into an empathic dialogue with women, offering them a listening ear, emotional participation, and space for action. To them, as well as to the men who followed him, he addressed messages of salvation, announced the demands of the Kingdom, and asked for radical choices. Women were not considered a separate category, to be marginalised or pitied, and they shared the Master of Galilee’s life, expectations and actions. This is why the disciples were embarrassed and did not understand his mature and balanced way of relating to women and, above all, they had difficulty accepting his freedom from conditioning and taboos. In fact, the female body in Jewish culture was kept under control so as not to contaminate the sacred (Numbers 15, 38). Therefore, women were excluded from the activities of worship by means of strict regulations. Instead, with Jesus this no longer represented a place and cause of segregation and exclusion because nothing can make a person impure except the evil that she commits and that is born from the depths of her deviated heart (Mark 7,15). In the same way, he showed himself to be free of all prejudicial limitations; therefore, today we would call him an inclusive man. He expresses it well in the dialogue with the Samaritan woman where he makes it explicit how God’s presence is not linked to a sacred place (the Temple). In addition, the relationship with the transcendent is not the privilege of an ethnic group (Jewish), a social or religious condition (the minister of worship) or a sex (male). Instead, it is possible for every person who knows how to welcome him “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:23).

Later on, Jesus' followers were not always congruent with his free behavior. For example, “They marveled that he was talking with a woman” (John 4, 27); they resented and were demonstrably jealous of Magdalene's authority (see also the Gnostic texts); they re-proposed traditional roles (“you wives are submissive to your husbands”); and, old patriarchal frameworks (“the woman learns in silence, in full submission. I do not allow the woman to teach or to rule over the man”, 1 Timothy 2:11-12). Yet, in the communities of the early communities, we find women, such as Lydia of Philippi, Tabitha, Priscilla, Cloe, Nymph, who offered hospitality in their homes, true places of welcome, prayer and evangelisation. Additionally, they were Christians engaged in the field of charity, diaconate, catechesis, evangelisation, mission and apostolate. For example, the women mentioned with respect and gratitude by the Apostle Paul: the deaconess Phoebe, the missionaries Priscilla, Evodia and Synthias, the apostle Junia, the evangelisers Trifena, Trifosa and Persis, the benefactresses Apfia and Ninfa. However, neither the women’s active nor collaborating presence, or the example of Jesus were decisive in providing for an inclusive framework to the nascent church. A structure that embraced the culture and patriarchal structures dominant in the surrounding societies with which it came into contact. Magdalene was soon forgotten (St Paul does not even mention her) and misrepresented (she went from being a disciple to a repentant prostitute since Gregory the Great), deaconesses played an increasingly marginal role, female prophecy was stifled, wives were returned to their role of submissive brides, and women's bodies became taboo again.

Ancient gynaecophobia

The ancient Christian authors essentially shared the anthropology of Greco-Roman culture, which placed the superiority of the male at its centre, and were essentially in agreement in reaffirming the imperfection and insufficiency of woman’s nature, who were born to be subject to man. For St Augustine, the two sexes were created in the image of God in substantial spiritual equality; nevertheless, female subordination was determined by the order of creation. The conception that passed on through Christianity was strengthened with its confrontation with Aristotle’s anthropology, i.e. the male gender was the model of the human and the woman was considered an incomplete male. This view was accepted and integrated into Scholastic philosophy and, specifically, into Thomas Aquinas’ theology, and over the centuries formed the basis of the inadequacy of the female gender both to perform the tasks of power and to represent the very image of God. This lack of knowledge of female physiology, and the fear of being contaminated by an impure person, served to increase the male fears of women's sexuality, which had to be kept in check and away from sacred places. Let us remember the Franciscan Alvaro Pelayo, who, in De statu et planctu ecclesiae , gave one hundred and two reasons to demonstrate not only their inferiority, but also the danger women represented: “origin of sin, weapon of the devil, expulsion from paradise, mother of error, corruption of the ancient law”. The obsession with the female body, desired and at the same time refused and rejected, appeared strongly in the treatises against the witches, which manifested itself in a growing fear of women who became scapegoats of ancient and deep-rooted anguish for several centuries.

In the twelfth century, during a consolidated process of the Church’s institutionalization, the law of ecclesiastical celibacy became established. However, this too inevitably favored the affirmation of a negative conception of women, who were removed from sacred places because they were considered impure. The continuous transgression on the part of the clergy led the Council of Trent to implement a broader and more appropriate educational approach. This implementation aimed -through the institution of seminaries-, at the spiritual and cultural formation of the clergy, who were educated severely and separated from the lay world. A telling sign of this was Paolo Segneri’s pedagogy, who identified women as the pinnacle of danger. To say the word “body” was to indicate a permanent threat to the virtuous life. Hence, the increase in precepts in which the suspicion of sin weighed on the very nature of women, who were perceived as threatening, characterized the Church of the Counter-Reformation up to the threshold of the Second Vatican Council.

Overcoming fear

The rediscovery of women’s dignity was certainly helped by Marian devotion. It was this that inspired certain founders, including Guglielmo da Vercelli, to plan a double community, involving men and women, and led by a woman, the abbess. This is what happened at the Goleto monastery, and it’s fascinating history remains visible in Irpinia today. Moreover, there are examples in the Church’s history of fruitful friendships between men and women. How could we understand, otherwise, the profound and intense understanding between Clare and Francis of Assisi who present and experience a fraternity-sorority in which anyone who wants to follow the poor Christ and wishes to establish relationships of mutual support is welcomed. We would not be able to understand the many experiences of religious life, such as those founded from the common work of Frances de Chantal with Francis de Sales, of Louise de Marillac with Vincent de Paul, of Leopoldina Naudet with Gaspare Bertoni, to name just a few. We could not avail ourselves today of innovative communities established by the prophetic provocations of missionary work if there had not been pairs of founders like Maria Mazzarello and Don Bosco, Teresa Grigolini and Daniele Comboni or Teresa Merlo and James Alberione. In addition, we would not understand the many friendships that have been nourished by faith and common passions. Moving forward to a time closer to our own, how can we fail to recall the mystical journey that united Adrienne von Speyr with Hans Urs von Balthasar and the cultural activism of Romana Guarnieri who indissolubly bound her life to Don Giuseppe de Luca? These examples are marked by intense relationships of profound consonance, of intimate and sincere affection, of mystical modesty. In feeling rooted in Christ, love becomes the way to overcome fears, a space for freedom and maturation, and for reformulating the relationship between a man and a woman in the friendly dimension of mutual support.

The return to utopia

Today, is there still any reason to talk about a fear of women? No one believes in witches anymore, and there are numerous other scapegoats that have catalyzed humanity’s fears. A culture of anti-discrimination based on gender has finally taken hold, and Pope Francis has begun a fundamental process of declericalization in our Church, by continually urging the meaningful presence of women in the structures of the ecclesial community.

Despite the many cultural changes in which we are participants, the churches’ institutions still struggle to accept women in roles of responsibility. This is probably because not enough work has been done on the formation of the clergy who at times, as Cardinal Marc Ouellet recently stated, “do not have a balanced relationship with women” because they have not been educated to interact through exchanges and debate. Men should reflect on themselves and on their often-violent masculinity, on the difficulty of accepting human diversity and fragility, and on the complexity of sharing feelings and projects with the opposite sex. They should learn to love women, and recognize them as singularities, and accept to share authority and responsibility with them. Perhaps it would then be appropriate to resume the poetic and utopian vision of certain sacred texts. In the origins’ mythical tale, in fact, Adam's encounter with Eve is not marked by fear, but by the wonder of discovering a “you” in which we are reflected. In the same poetic horizon is the Song of Songs, which takes up and exalts the reciprocity of the genders in an extraordinary love song. For here, in which it is the autonomous and responsible woman who recognizes herself in the man, he puts aside his abusive behavior to find shelter in her. In love, the logic of domination vanishes and fear has no reason to exist.

by Adriana Valerio

Historian and theologian, professor of History of Christianity and the Churches at the University Federico II of Naples,

author of the book “Donne e Chiesa. Una storia di genere” [Women and the Church. A History of Gender], Carocci,

and “Il potere e le donne nella Chiesa” [Power and Women in the Church], Laterza.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti