Nuns, stories

Mary Keller and the others: modern religious women beyond stereotypes

In order to find the modern nun, to discover how she lives, loves and prays, we have to do a cleaning job. Forget the old images and put aside the stereotypes that have been handed down to us. It is difficult, when talking about nuns and sisters, to let reality win. It is easier to cling to what literature has told us, to accept the history written by men, to abandon oneself uncritically to the tragic, amusing or grotesque images of nuns portrayed by the cinema or television. It still happens today that in the collective imagination the figure of the nun is assimilated to that of the nun of Monza, that tragic example of the constraint of cloistered life, to that of many young women who in times gone by were forced into the convent by families who could not give them an adequate dowry; namely, fragile women and slaves. Forced. In the past by their family, today by poverty in the most desperate places on the planet.

Only victims?

Attempts have been made to create a truer image, one that adheres to reality. German television has tried with Sister Lotte in Per amor del cielo [For heaven's sake], and Italian television with Sister Angela in Che Dio ci aiuti. These are generous but fragile attempts to focus on the comic, or as in the film Sister Act, on the grotesque in order to overturn a predominant collective imagination that remains. There, in which the splendor of figures from the past, Clare, for example, or Hildegard of Bingen, assume a residual role. This is a small thing in the face of the stereotype of victimhood and constraint.

Let us commence with the past. Was it really like this? Was the choice of the convent obligatory? Alternatively, was that seed there even in dark times, that seed of freedom which today is vigorous in the world of women religious, their capacity for discernment? Were the women who followed St. Clare and obtained the pope’s vow of poverty not the masters of their actions? In addition, did the other anonymous and obscure women of the Middle Ages and the following centuries go to the convent only because someone forced them to?

If history were not written almost exclusively by men, if they had been able to pass on to us what they thought even in those distant times, we would have found the seed of freedom in many vocations. Many of them would have told us that they preferred the convent, the company of other women, chastity, a life in faith, of prayer to a hostile world that in the best of cases scenarios made them their husbands’ slaves. That they chose to live in prayer rather than submit to the rules of men who considered them little more than slaves. They would point out to us that faith was their freedom, and the convent an opportunity for emancipation from the oppression and violence of society

To speak of more recent times, does the story of Sister Frances Xavier Cabrini suggest some form of awe? Twenty-eight crisscrossing the Atlantic on precarious boats, then the crossing of the , and to unknown countries. With her group of seven sisters, the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, she raised funds, built schools, kindergartens, convinced governments, and improved the lives of thousands of immigrants. Moreover, this at a time when women in Italy were not even considered citizens and had no right to possess goods.

The First nuns

Let us try, therefore, to look at reality with an attentive and unprejudiced eye. We will find surprises there, some of which are important ones. In the newspapers we find the names of important religious women, “first nuns”, we could call them, vanguards of a larger group of nuns who are not only well established in the world, but who aspire to change it.

Norma Pimentel, who organizes help for migrants who try to enter the United States at the borders, is counted among Time magazine’s top one hundred most influential people. Alessandra Smerilli is a State Counsellor of the Vatican. Giuliana Galli was vice-president of the Compagnia di San Paolo, one of the most important European banking foundations. We could name others, but we will stop here, for you will find them in other pages of Women Church World. What is certain, however, is that in every sector of society there are now nuns who occupy important positions. They work and acquire leading roles in medicine, law and social studies, and public health. They are accountants, lawyers, engineers, and architects. They enter into roles that seem foreign to the world of meditation and prayer and not on tiptoe as they do so. In addition, there are nuns who are journalists, nuns in information marketing; and those who are committed to the environment, who use and master IT.

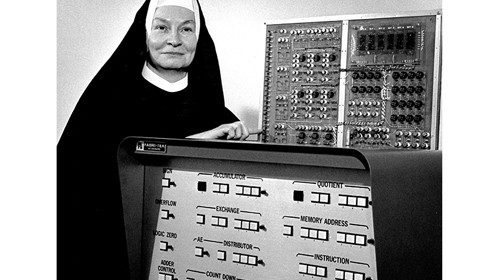

Indeed, they are often a vanguard in this field as well. To start, there is Sister Mary Keller, who contributed to the development of Basic, the programming language. She foresaw the advent of the Internet and supported the importance of computer tools and their possible positive impact on society in the education of young people when they were not yet so widespread.

Born in 1913 in Ohio, she was the first people to obtain a doctorate in computer science in the United States in 1965. A true precursor of the times, Mary Keller maintained that the computer could be a tool for exercising Christian virtues, commencing with patience and humility.

There are now many others. Alongside them are the nuns who, in their convents, continue to practice traditional trades, cultivating the garden, sewing and embroidering. A question about them is also appropriate: are nuns dated or modern in a world that, in order not to go to ruin, needs new models of work and progress? A return to the love of the earth and its fruits? The many young people who today are concerned about the fate of the planet and want to preserve its offerings, who prefer to return to the land and manual labor, have in the humble sisters of the monasteries a valuable indication.

Among the new nuns, there are those who prefer seclusion. This may seem to be in contradiction with their strong presence in the world, the excellence of certain positions, and the prominence in professions that until some time ago were only secular. Why, many ask, do young women prefer to withdraw into prayer, into an intimate and exclusive relationship with God?

It is a contradiction only if one looks at the nuns through old lenses and, in the seclusion and the choice of isolation, one sees the break with the world, the fear of what is outside the convent. We then find it is not like this. Therefore, it is sufficient to read their interviews, the few words they have felt the need to say, to understand that the cloister is the place where the very absence of noise allows for a truer relationship with the world. Even from behind the grated windows, we can communicate. In fact, this happened during the lockdown when WhatsApp messages of comfort arrived from the cloistered convents, and which were an invitation to make the imposed silence a new moment on which to build a relationship with others and reflect beyond distractions.

The information technology used by those women separated by the convent’s grated windows became an instrument of prayer for -and with- others. A means of communication between men and women and God. Prayer - Sister Mary Keller was right - can also travel via the internet; it can be nourished by Instagram, WhatsApp, and Twitter.

The incomprehensible

Today, nuns operate internationally, and with the tools of the world; however, there is a moment when dialoguing with a nun - even a “modern” nun - when it is necessary to accept the incomprehensible. It happens when we talk about vocation. When and why did it happen? What had they experienced? What proof do they possess that the call was the right one? When did they become sure of their path? Was the fruit of meditation their choice, of hard work on themselves? Alternatively, did it happen suddenly like St. Paul’s falling from his horse? It is difficult to find the words. When this happens, it is difficult to understand. Not only for those who ask, but also for those who have made the choice.

“The Lord called me”. “I understood that my life needed Jesus”. “The Church is a mother, my mother; only in her do I feel warmth and fullness”. “I was looking for freedom and grace; I found them in the convent with the others”. “At a certain point in my life I understood that I had to leave everything to get everything”. “If I had to explain the vocation to those who have not had it, I would say that it is similar to a state of falling in love, when the other is everything for you, you feel that your life has no meaning without him. For me Jesus is this”.

No doubts? No desire to go back? No fears? Many doubts, many fears, sometimes the feeling that the road taken is not the right one. Then you pray. And something happens.

The vocation crisis

Today, data shows that the number of vocations has shrunk. In 2018, there were 641,661 women religious, which is more than seven thousand less than the previous year. The number of priests has also decreased while the number of Catholics has increased. Europe is the continent where the reduction is most evident, followed by America and Oceania; however, the number of vocations is increasing in Africa.

Are these numbers worrisome? Certainly, the Church needs to question herself. Women religious have always constituted the majority of her people. A silent or silenced majority (depending on the point of view), but an important one in the formation of the soul and image of the Church.

Two questions then arise. What is the reason for the crisis? Followed by, can the decline in female vocations be assimilated to that of men? Many think this is a consequence of a lack of interest in religion, a reduction in grace, an affirmation of secularization and a reduction in interest in the sacred. There are many who think this way. It is an opinion that is flanked by another that takes a more specifically feminine point of view.

Today, women -especially in Western countries- who want to do something for others receive offer from thousands of associations and organizations in which they can exercise their vocation.

The Church, with her masculine codes and her scarce consideration of women’s contribution in decision-making spheres, has become less attractive to women accustomed to doing well when they can do so freely. The second question directly concerns the Church. What would a rigidly masculine institution become if the numerical contribution of women was further reduced? What would happen if her backbone made up of women religious, would decline further? I think there is no doubt that it would be enormously detrimental.

by Ritanna Armeni

A road for a Nun

A road in Karachi is named after Sister Berchman Conway, an Irish Catholic missionary who was honored in this way for her work in education. Berchman’s Road was inaugurated by the authorities in the presence of teachers, nuns, students and parents. Born in 1929, Sr. Berchman has lived in Pakistan since 1954 and has taught English and mathematics for 60 years. Her students include former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and astrophysicist Nergis Mavalvala.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti