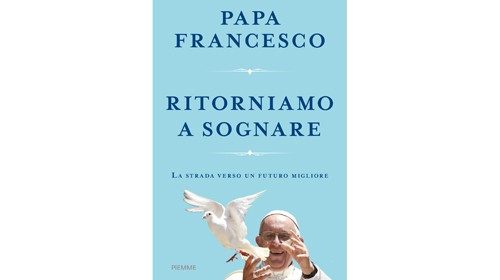

From the outset, one of Pope Francis’ concerns has been to integrate the presence and sensitivity of women in Vatican decision-making processes more effectively. During his pontificate, he has wondered how to ensure that women can lead and especially shape culture. The Pontiff confided this to British journalist Austen Ivereigh, and the book that emerged from the Covid crisis, entitled Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future is a result of their discussions.

Over the years, the Pope has appointed several women to important positions in the Vatican hierarchy. Nevertheless, he has been blamed for not doing enough, and he is aware of this. In turn, he justifies himself by pointing out that these women were chosen for their competence, and to shape the vision and mindset of Church government. In many instances, he wanted women as consultants to Vatican bodies, so that they could use their influence while preserving their independence.

These words are capable of making many Catholic women’s hearts beat with joy and pride. After all, and on whether the Pontiff trusts women there is no doubt, he admires their strength and their audacity, their flexibility, their sagacity, and their pragmatism. The book is also crisscrossed throughout with the women’s faces who have left a mark on him; for example, a nun who saved his life by having the courage to use her experience against the advice of doctors, and his teacher whose silence touched him most deeply.

The Pope touches a sore point in which distrust, fears and resistance converge when he reiterates that women do not need to be priests to assume leadership roles in the Catholic Church. When he warns against the risk of clericalization, he goes to the heart of the perplexities present in some fringes of the Catholic universe and beyond; in sum, this refers to the exclusion of women from ordained ministries and their perhaps consequent subordination.

Though the criticism has not happened often, it has been harsh. For example, in one statement, members of the Conference for the Ordination of Women state that every woman, from parish worker to Vatican counselor, is subject to the authority of an ordained man. While in France, the theologian Anne Soupa asks, in a provocative tone: what could a handful of female consultants possibly do against the crocodiles of the Curia?

For Francis to say that women do not govern because they are not priests is clericalist and disrespectful. The fact remains, as has already been pointed out on several occasions, a reflection on women’s Christian life obliges us to pose the question of the priesthood in terms of powers, the balance of these powers and the reality of the ministerial priesthood in its relation to baptismal priesthood.

by Romilda Ferrauto

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti