A feminist

Christine de Pizan, a life that speaks to women today

Born in Venice in 1365, Christine was cared for by a father who was attentive to her education and saw that she did not suffer any form of gender bias. In the Pizzano family (original surname), patriarchy was minimized by an enlightened paternal model. The presence and accessibility of books. A possession of the tools through which to assimilate knowledge. These three parameters, which even today are not at all taken for granted even if they are recognized, were rocks at that time. Kilometers of cliffs overlooking the void. If Christine de Pizan is considered the first woman to take up an intellectual profession, one of the forerunners of feminism and the first lay historian, it is because she was one of the women - more singular than rare - in a position to climb that triad of possibilities.

The educated environment in which Christine was fortunate enough to grow up, could not guarantee, no matter what, the possibility to evolve her position to any woman. The discrimination was not so much in the culture itself, but in the possibility of accessing it; in addition, in the personality that is formed within these parameters of possibility. Tommaso da Pizzano was a doctor and astrologer, whose sensitivity supported his daughter’s aptitudes. The complicity between father and daughter was the miraculous ingredient that destined Christine’s life, for she was able -even before studying-, to form her own wild, enlightened, independent individuality.

Independence is one of the crucial aspects of Pizan’s life, so much so that it drove her to tell herself what she could do to fulfil her individuality as a woman, as a worker and as a citizen; and it was the need for this independence that built her figure as an autonomous professional year after year.

In 1369, in fact, Thomas moved with his whole family to the court of the King of France Charles V, where he worked as a doctor. Christine was four years old, and Paris, at that time, was a hub of civilization, a European capital in which new political and literary ideas circulated. Christine mentions that period several times in her works, recalling the tightrope walkers who crossed through the air on a rope stretched between the two towers of Notre Dame; or the procession of the Sultan of Egypt who visited the kings of France: a crowd of exotic characters that unraveled her thinking. Most of all, Christine had access to the immense court library, which was one of the richest in Europe, which allowed her to learn to read and write.

At the age of fifteen, Christine was given in marriage to Étienne de Castel, the king’s notary and secretary, nine years her senior. As avant-garde as he was, the de Pizan family, according to custom, arranged the marriage and Christine lived with her husband for ten years. He was a man whom, however, she loved very much and this aspect, in her formation, affected the extent of that love - as well as the one that had united her to her father - taught her to respect herself.

They had children. Christine was a woman, a mother, a wife. In her works, she notes several times how painful it was to give up the time to read in those years, but above all, how tiring it was to give up time to devote to herself. A bold reflection, for an articulate and courageous woman of those times.

When her husband died, Christine was twenty-five years old. She suddenly found herself alone, with children to support.

It was at that moment, when she was experiencing pain, and loneliness, that Christine applied that conscious reflection to her own situation as an individual. A process that belonged extensively to the creative act: that of plunging one’s gaze into oneself and drawing out something new. A creation born of one’s own thought, which generates other thoughts. It was out of necessity - as is often the case - that Christine achieved her own transformation, thanks, however, to all the emancipatory substrate on which her personality was already grafted.

Christine had to look after her own surviving family, had to manage the accounts of a wealthy estate, which, however, had always been looked after by her husband. It was at that moment that Pizan realized that women were always sidelined in the management of family accounts, bureaucratic issues, and everything that was outside of domestic duties or childcare.

Christine needed all of her husband’s back wages that had been forgotten in the sovereign’s pockets, as it was a noble custom to defer compensation for their employees. Pizan had the autonomy and the tools to pursue her own reasons, and she started court cases and legal battles that lasted for years. During this time, she built up her own political thinking, acquiring notions and the flair of a strategist, and it was during this period, in recognition of her own difficulties, that Christine began to establish herself as a lay intellectual.

Christine recounts how this recognition came about in one of personal anecdotes that characterizes her work. As soon as she was widowed, she had a dream in which she was aboard a ship during a terrible storm, without a captain - probably a figure representing her husband. Left alone to navigate the stormy ship, Christine invoked Fortuna (the goddess of fortune and the personification of luck), who began to palpate her, and only then - while Fortuna was touching her – did Christine realize that she no longer had her wedding ring, and that her body had taken on the features of a man. To weather the storm it was necessary to assume a male appearance. When she awoke, Christine writes, she told herself, “I felt much lighter than usual”. Whether the dream is true or imaginary, it does not matter. However, we can understand that from that moment onwards Christine understood that her approach would have to change in order to impose her own voice as a woman. The mechanism is the one that belongs to most female artists and workers who, over the centuries, have had and continue to have to impose their own vision in order to overpower that of the male universe. To make a comparison, it is indicative of what Agnese thinks in Anna Banti’s book Un grido lacerante [A lacerating cry] (1981): “No, she had not claimed anything other than equality of the mind and freedom to work that should exist between men and women, which still tormented her as an elderly protester”.

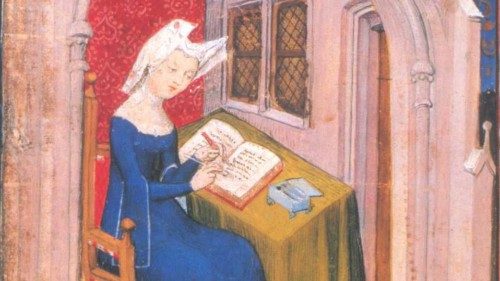

From that moment on, Christine began to write treatises related to politics and gender issues that resulted in the famous La città delle dame [The City of Ladies] in 1405, which was intended to contradict the misogynistic clichés caused especially by Jean de Meung’s Roman de la Rose. The real emancipatory process, however, happened with concrete facts. More than with her books, Christine’s entrepreneurial and professional strength was demonstrated by her own life, and her exemplary testimony: her many books were recognized and in demand in all the courts of Europe; she herself ran the workshop where the texts were copied; a place of work for master calligraphers and miniature designers - mostly professional women.

Her role as a worker and intellectual did not need to be told because it was amply demonstrated.

In 1415, after fifteen years of enormous success, France was routed at the battle of Agincourt by Henry V and a section of the French side with the English. In 1418, the Burgundians sacked Paris. It was during this period that Christine remained silent. For prudence sake she withdrew to a beautiful and rich monastery whose abbess was a daughter of the king (Christine enjoyed a network of very influential friends). In the calmness of the retreat, and far from the violence that was destroying France, Christine confronted her old age and began to be familiar with the thought of death. She is old now, over fifty, and in the quiet of the monastic rooms, she forces herself to withdraw from her fighting life. Yet, someone, after eleven years of absolute calm, returned to stir her imagination, to question her intellectual curiosity as a citizen. This young girl appeared on the battlefield against the English army, who was animated by a prophetic spirit, sent by God, who puts the enemy army to fire and sword. This was Joan of Arc, and it was she who urged Christine to start writing again and to create what today we refer to as an instant-book about her life, whose writing will accompany Pizan until her death in 1430 in the monastery. The book is called The Poem of Joan of Arc, which begins as follows: I, Christine, who have wept for eleven years locked in the abbey, now for the first time laugh, laugh with joy.

by Rossella Milone

The author

Rossella Milone lives and works in Rome. She has published for Einaudi: Cattiva (finalist Volponi Prize, 2018), Poche parole, moltissime cose (2013), La memoria dei vivi (2008); for Minimum Fax Il silenzio del lottatore (2015); for Laterza Nella pancia, sulla schiena, tra le mani (2010); for Avagliano Prendetevi cura delle bambine (2007). She writes for the Italian national magazines L'Espresso, TuttoLibri and Donna Moderna. Rossella Milone coordinates the project dedicated to the dissemination and promotion of the story Cathedral, on www.osservatorio cattedrale.com

Poem

I am alone

I am alone, and alone I want to remain.

I am alone, my sweet friend has left me;

I am alone, without companion or master,

I am alone, sorrowful and sad,

I am alone, languishing in pain,

I am alone, lost as none,

I am alone, left without a friend.

I am alone, at the door or at the window,

I am alone, hiding in a corner,

I am alone, feeding on tears,

I am alone, in pain or quiet,

I am alone, there is nothing sadder,

I am alone, locked in my room,

I am alone, left without a friend

I am alone, wherever and everywhere I am;

I am alone, whether I go or stay,

I am alone, more than any other creature on earth.

I am alone, abandoned by all,

I am alone, harshly humiliated

I am alone, often in tears,

I am alone, without a friend.

Princes, my sorrow has now begun:

I am alone, threatened by pain,

I am alone, blacker than black,

I am alone without a friend,

abandoned.

Christine de Pizan’s poem written after the death of her husband Etienne in 1390 for an epidemic

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti