Brave Nouns in Support of Italians in the Americas

At the end of the nineteenth century, a river of sorrowful humanity crossed the oceans. This river was composed of millions of people who left the Old Continent for the Americas in search of fortune. Between 1836 and 1914, it is estimated that thirty million Europeans emigrated to North America; and, of these, at least four million were Italians, and an equal number travelled to Argentina and Brazil.

To help them on their way, it was not their countries of origin, but –and above all else- the religious men and women who did so. The first to be deeply shocked by this exodus was the bishop of Piacenza, Giovanni Battista Scalabrini (1839-1905). “In Milan - he wrote - I was a spectator of a scene that left an impression of deep sadness on my soul. I saw the vast hall, the side porticos and the adjacent square invaded by three or four hundred poorly dressed individuals, divided into different groups. On their tanned faces, furrowed by the early wrinkles which are usually etched from the deprivation, shone the tumult of the affections that stirred their hearts at that moment”.

You can imagine the shock from the separation of those who left and those who did not. On the Naples pier, sometimes poor women remained, without a penny in their pockets because all their belongings had been committed to buy the ship’s ticket. Desperate women, at the mercy of everyone.

For the “discarded” women of Naples, four Salesian Sisters, Daughters of Mary Help of Christians opened a shelter which proved to be fundamental in the accommodation of emigrants who remained on land, to care for them, to accompany them to a second medical examination, and then, if all was well, to help them to board. In 1911, Sister Clotilde Lalatta confided to her superior: “For us, the hours of common life are very scarce, and being insufficient for work, the hours are very compromised. On the steamships’ departure days, we have to go to the port once or twice a day; at home, to sew, to iron, to clean, to assist and serve the hostesses, to wait at the door. Then the commissions and expenses, then the visits of the doctors treating the women, the receptions of those people who have the right to see the house”.

This is just a small example of what an exceptional effort religious women made to assist this immense movement of peoples. For many, the challenges of missionary work soon arrived. As Sister Grazia Loparco, historian, professor at the Pontifical Faculty of Educational Sciences Auxilium recalls “Like other founders, Don Bosco felt challenged by the precariousness in which migrants travelled. In fact, before arriving at the dreamed of Patagonia, the Salesian missions in Argentina and Uruguay took an interest in Italian families who often, it was said, lost their faith in the ocean. On the operational level, many religious institutes, in addition to offering spiritual assistance, social and legal support, had schools and education as strong points. In 1877, six young Daughters of Mary Help of Christians inaugurated missionary expeditions in South America, where they began to work among the families of migrants. Later, under the guidance of Don Bosco’s successor, Fr. Michele Rua, the religious, like the Salesians, expanded their field of action first in South America, then in the Middle East, Switzerland, Belgium, England and a few years later in the United States”.

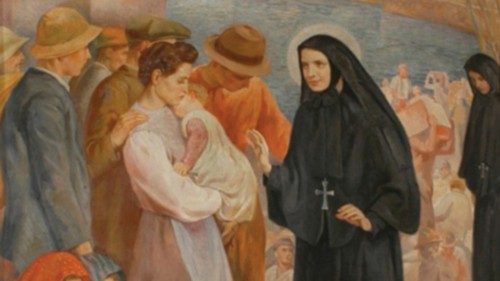

To help the emigrants was a moral duty. The Vatican, however, was worried because many lost their faith during the crossing or because they did not find a parish waiting for them where they could speak their own language; instead, they encountered actively anticlerical, socialist and Masonic propaganda. The masses of emigrants thus became the object of re-evangelization. What is strange is the commitment of Sister Francesca Saverio Cabrini, the first American citizen to be declared a saint. The Sister was born into a wealthy family in Northern Italy in 1850, and founded the Congregation of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus at the age of thirty. Pope Leo XIII expressly sent her to evangelize the Americas, and in 1889 Sister Cabrini reached New York. It had been a hard journey, as an emigrant among emigrants; but, an even harder reality awaited her. The Archbishop of New York, Michael Augustine Corrigan, was hostile to her and told her in nu uncertain terms that there was nothing for her to do in New York, and that she should return to Italy.

That is the way things were at that time. There was a very strong mutual distrust and clashes between groups of various nationalities occurred, even between Catholics. “The Italians stink - Archbishop Corrigan wrote to the Pope - and if they had to go to the main church the others would no longer come”.

In 1887, Propaganda Fide authorized national parishes in the United States, which were also called personal or linguistic parishes. However, as explains Matteo Sanfilippo, professor at the University of Tuscia “the national divisions also split the religious orders in charge of protecting their migrants. Frequently, these divisions were very complex in the newly formed States. After all, it is well known that the missionaries from northern Italy despised the migrants and the priests of southern Italy, but the same happened in Germany where the North has always despised Bavaria. In the face of such absolute confusion, Prior to his death, Scalabrini proposed the establishment of a Vatican secretariat that would take care of all emigrants, and help overcome national biases: Catholics were to be followed along universal lines and not on the basis of national origins”.

Sister Cabrini rolled up her sleeves and found the first funding on her own, while terrible and exciting years were to follow. She and her sisters began in the smelly alleys of Little Italy, but this nun was a tireless traveler, and made twenty-eight Atlantic crossings and the crossing of the Andes on horseback to reach Buenos Aires from Panama. It is no wonder, for Sister Cabrini was an interpreter of the new spirit of the times, when nuns went to the front line, outside convents, in the world, to assist the lowly, and to witness the Gospel. Nor did the patriotic value of her commitment escape her. Shortly after 1890, in New Orleans, unknown persons murdered the local police chief and the blame fell without proof on the “Dagos”, the torn, malnourished, and homeless Italians who crowded the city. There were horrible episodes of lynchings in the streets. The Cabrini went to the city and announced “The Italians were being slandered, to the point that the crowd, incited by those who wanted their expulsion, lynched dozens of them”.

America was a great challenge. Italian religious women opened schools, kindergartens, hospitals, orphanages for “their” emigrant brethren. In most instances, they had no qualifications, and therefore they could only take care of early childhood, not high school. “At the beginning of the twentieth century - recalls the historian Maria Susanna Garroni, university professor and editor of the book Sorelle d’Oltreoceano [Overseas Sisters] - Italian religious women often came from very small towns and from a pre-industrial country. When they disembarked in the United States, they remained disoriented by the modernity of the metropolis and confronted with a growing industrial society”.

They saw the “animalistic spirits” of capitalism at work. “They spoke of their nostalgia for Italy, as well as their bewilderment in standing before the skyscrapers, the wide streets, and the swarming crowds. In addition, they had to deal with the Protestant clergy, and discovered that, apart from a few enlightened bishops who paved the way for them, no one would help them. Yes, perhaps they found some initial charitable funding, but then they had to do it all by themselves because even the pious had to support themselves economically.

The American society forced them to be industrious and to stand on their own two feet. When the Great Depression came, the older nuns even went along the streets to gather wild herbs to feed themselves. Many of them were forced to go to the police station. Moreover, the bishops were reluctant to intervene, because they were afraid of putting Italian Catholics in an even worse light. All this, in the end, forced them to evolve rapidly. At that time, Sister Cabrini, who came from a rich bourgeoisie family, showed particular managerial ability, but all of them were transformed by this, and emerged to be more enterprising, self-confident, evolved”.

The women’s congregations were strengthened, and many threw themselves into the enterprise. In the United States, Cabrinians, the Apostles of the Sacred Heart, the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, the Pious Philippine Teachers, the Baptists of Canon Alfonso Fusco, the Pallottines, the Sisters of St Dorothea (of Frassinetti), the Franciscans of Gemona, the Venerable Sisters were more numerous. In Argentina and Uruguay, in addition to the large group of Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, the Sisters of Mercy of Maria Rossello, the Daughters of Our Lady of the Garden of Chiavari, the Sisters of Mercy of Carlo Steeb of Verona, the Cabrinian Sisters and the Little Sisters of Charity of Don Orione. In Brazil, once again it was the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, and then the Scalabrinians, the Apostles of the Sacred Heart, the Cabrinian Sisters, and the Sisters of St Joseph of Chambery. A story for all, taken from Sister Loparco’s studies. In 1908, a group of Sisters from the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians opened in Paterson, near New York, which was a house with a school for the education and instruction of Italians. We know from their reports all about their efforts, successes and failures. For example, they were not at all prepped in English, and having had to impose a monthly fee, when they started out there was just a few pupils. In addition, the place was poor and unadorned, even if it was not lacking in light. The first books, arrived from the Consul of Italy as a gift.

However, the study of the English language, which was mandatory, and the Italian language was cultivated. At the end of the first year it was possible to submit an essay in either of the two languages. This was a fundamental step for the integration into the new reality. In the second year, 120 students arrived. The Italian families of Paterson, although very poor, agreed to pay a tuition fee because they recognized the usefulness of that parish school. Nevertheless, the road was an uphill one. “In 1911 - as Sister Loparco states in their report to Rome - the number had grown and would be even greater if the relatives did not have to pay a monthly fee, which seemed so prohibitive to them that they were forced to send their children to public schools”. But Paterson continued anyway; and as a consequence the Church participated in the founding of the new world.

By Francesco Grignetti

Journalist from “La Stampa” an Italian newspaper

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti