In many respects the apostolic work of Pope Francis can be compared to that of St. Augustine: the Bishop of Hippo who advocated a rigorous approach to inner church discipline yet kept a compassionate outlook to the human reality around him and he may be regarded as the first proponent of love as a political value. In De Civitate Dei, Augustine approaches secular history and politics with a methodical distrust and, envisages a ‘politics’ based on the perennial principles of divine revelation as constituting Christian identity.

Fratelli Tutti, the latest encyclical of Pope Francis re-proposes love as a political value and continues to represent the Lord’s compassionate gaze on the human misery. Yet it progressively redefines the idea of Christian identity. In fact, the heart of this encyclical is a radical challenge to all types of self-enclosed identities — local, cultural, political and religious. It challenges them to grow beyond themselves by finding the correct balance between integral growth and self-giving. It challenges them to do away with boundaries by dynamically and correctly correlating the local and the global, the political and the spiritual, the historical and the perennial aspects of their self-definitions. The Document prophetically proposes that the correct balance is not the safe balance, but the challenging balance — a balance that ensures progress.

An Economy of Care

Fratelli Tutti is not primarily concerned with the economic aspects of human welfare, but an awareness that economic inequality constitutes a major hindrance to the building up of true fraternity. Presupposing the magisterial teaching hitherto regarding private property and its just use (123), it addresses several contexts of modern life where attitude to material well-being causes divisions between individuals, nations and societies. Economic forces are at work, for example, behind increasing isolation and reduction of individuals into consumers (12), alienation and abandonment of individuals that are ‘no longer needed’ (18-19), reduction and misinterpretation of rights and opportunities (20, 22), propagation of hatred and violence through misinformation (45) violence under various cultural and political guises (25) and marginalization of immigrants (37). Not only individuals but even small nations are intimidated by the forces of market (51) and sometimes nations treat their neighbors with fear and mistrust, characteristic of individualistic ideology (152). Populism and liberal capitalism, the two dominant ideologies that control market and political psyche, manage only to mislead people for the benefit of few; and the left ideologies that may console smaller groups remain ineffective at the larger scale. Pope Francis points out that we cannot let the falsely conceived ideals of freedom and efficiency, as promoted by the market economy, determine our lives. He proposes inclusive decision-making (137-138), promotion of solidarity (114-117), and ‘re-envisaging the social role of property’ (118-120) among solutions to the situation. But above all, it is about being truly a brother. ‘A truly human and fraternal society will be capable of ensuring in an efficient and stable way that each of its members is accompanied at every stage of life.’ (109) And as the Pontiff explains with the help of the leading image of the Good Samaritan, the accompaniment involves both personal care given to one’s brother in need and ensuring that the systems of care are made use of (the inn in the parable, 78).

A Politics of Love

It is easy to see that in Fratelli Tutti, the Pope’s primary reference as system of care is the nation state and he builds on the traditional catholic view that the Church and the state need to co-operate for common good. The problems of our age are so large that they cannot be resolved only through co-operation between individuals or even between small groups (126). States have a significant role to play in this context. While states are ideally conceived as systems protecting those inviolable rights with which human beings are born and they are to flourish, in our present day they are dominated by the forces of market economy (172) and a collective form of individualism, the latter leading to exclusive nationalism (141, 152). Humanitarian crises in different parts of the world make migration inevitable and ensues a new interpretation of the inviolable rights of people for living with dignity — including right of land beyond the borders of their nations of origin (121-126). The pandemic situation also reveals the limits of governments dominated by economic and nationalistic concerns. Consequently, states need to affirm their authority over economy (177), and should look forward to ‘forging a common project for the human family, now and in the future’ (178). To block the prevalence of economics over politics, ‘it is essential to devise stronger and more efficiently organized international institutions, with functionaries who are appointed fairly by agreement among national governments, and empowered to impose sanctions’ (172). As a concrete measure, the Pope calls for a reform of the UN (173).

Here we are into the practical dimensions of the magisterial teachings of Pope emeritus Benedict XVI on the political aspect of love, summarily presented in Deus Caritas Est (28b) and further detailed in Caritas in Veritate (7 et passim). Commitment to common good, expressed in gestures of mutual care, becomes a power that can really transform the world. Charity enlightened by truth — about the true nature and dignity of humanity — is ‘the spiritual heart of politics’ (187). Here charity not only informs a personal act, but also aims to transform the social structures (186), empowering others to face miseries of the human condition on their own, with dignity (187). It helps politicians to overcome populist impulses and to find effective solutions to situations of social exclusion and injustices. Charity will drive them to move from fine discourse to concrete action, first and foremost in ensuring fundamental rights — like the right to food (189) — for all people and everywhere.

In order to make love a cultural and political value we must be ready to overcome the aspects of cultural fragmentation prevalent in our present-day society and to forego pursuit of success in view of real fruitfulness. It requires a special strength to be tender, to have ‘the love that draws near and becomes real’ (194). It requires also courage to start actions whose fruits will be reaped by others. Without these, the qualities of the Good Samaritan, there is no political love. It is with the same strength and courage, imbibed with the Christian hope that love can transform life and its structures, that the Pope calls for disavowal of terror — including that of war — in political activity and abolition of death penalty (255-270).

An Ethnicity of Universal Fraternity

Crossing the boarders set by ethnic (and religious) differences with courage and generosity is a key moment in the story of the Good Samaritan. Still, the stranger on the road is a problematic sign for our times — as revealed by the context of migration. The national and cultural heritages that constitute ethnicities are of great importance — they are not to be simply set aside or neglected. Yet cultures are to be encouraged to open to other cultures in a mutually enriching dialogue; and the same is true of national identities. Ethnicities are to move forward, while being grounded in their original cultural substratum (134-137). Of course, such encounters are to be backed with governmental action such as developmental aid to weaker nations and political validation and accommodation of emigrants. But the major attention of Fratelli Tutti is on building up of the larger family — the human family. The true worth of a nation is not in its ability to think of itself as a nation but also as a part of a larger human family (141).

The Document certainly alludes to the theological foundation of human family — that all are children of one Father (46) and all are part of the universal plan of redemption in Christ (85). But the more frequent appeal is to the human nature itself (87). Human beings have an innate (70) capacity and almost a necessity to be connected to one another. Perhaps the Holy Father perceives this as a more inclusive ground for realization of universal fraternity. But this innate ability has a theological dimension (93) and moral virtues find their fuller meaning only with ‘charity that God infuses’ (91). This love that helps us to seek for others the best in their lives (104) and opens up what is best in us for the good of all around us. This love, which is universal in both geographic and existential dimensions, is the real life-force of human fraternity.

The Holy Father takes special effort to point out that this universalism will become an empty notion without a preferential outlook for those who are in gravest need (187, existential foreigner in 97), and without care to respect, preserve and enrich individual (100, 106-111) and local identities (142-153). His ‘war’ is on the self-enclosed identities (e.g., local narcissism 146; narrow nationalism 11), and ideologies like individualism, that make creative dialogue impossible.

A Culture of Dialogue

A significant part of Pope Francis’ criticism of contemporary culture is directed against opinionated standpoints, false ideologies, misinformation perpetrated in everyday life (gossips) and in social media, and shallow relationships promoted in new media culture. After defining real sociality as getting near and getting real in spirit of fraternity, the Pope contemplates more the world of opinions and beliefs and its relation to truth in the last three chapters of Fratelli Tutti.

Truth has historical and contextual manifestations, which need to reform themselves through encounter with its perennial embodiments. Since nobody can claim a monopoly on the latter, the only possible way ahead is getting into sincere dialogue, with the conviction that others have something worthwhile to contribute. With patience and commitment, it is possible to build consensus, which are prejudicial neither to objective truth nor to genuine interests of the society. Encountering the other, in sincere aspiration to find points of contact and platforms to promote work for common good, need to develop into a culture.

Patience with the social reality is key in this process. Remarkable is the Pontiff’s admission that even refusal to accept good ideas and violent social protests can have a genuine context (219). Conflicts with those who offend our dignity are legitimate and genuine love requires our commitment to make them realize their mistakes (241). Forgiveness in social context, thus, is neither a mute compromise with evil, nor forgetting the wounds of the past but the capacity to reach peace through dialogue and honest negotiation.

The sincerity of the Holy Father’s proposals for meaningful co-existence of human beings can be seen in his readiness to apply the same principle — rejection of self-enclosed, non-dialogical identities — to the plurality of religions as well. Fratelli Tutti is not only offering a creative challenge to the contemporary world, but also is proposing numerous points for introspection and self-reform to all units and levels of ecclesial life.

For the world to move forward and to realize the common call of all humanity to live as one family, the only way is to engage in open and sincere dialogue, not only at the personal level, but also at all levels of social and political life. That is the central message of Fratelli Tutti, the way for universal fraternity.

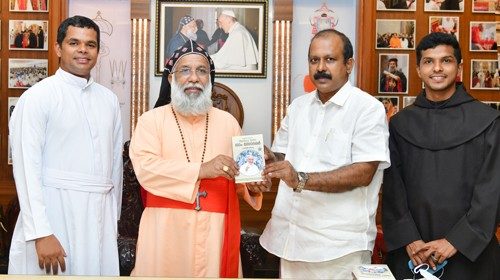

Cardinal Baselios Cleemis

Major Archbishop-Catholicos, Trivandrum, India

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti