Are human beings already brothers and sisters or is this what we must become? The heart of this challenging encyclical is the conviction that fraternity is both our deepest present identity and our future vocation. We are invited to become brothers and sisters in Christ in a way that we can hardly now envisage. ‘Beloved, we are God’s children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.’ (1 John 3:2).

This is in part an adventure of the imagination. By imagination I do not mean “imaginary”, fantasy, but a transformation of how we are in the world. A Christian imagination is the power of the Holy Spirit leading us into all truth. It is ‘the mind of Christ’ (1 Corinthians 2:16).

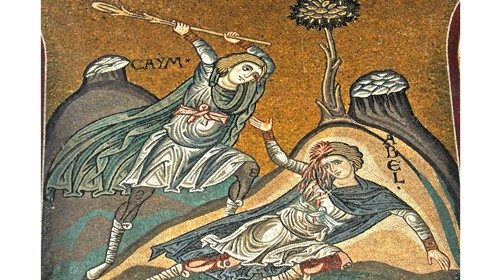

A fraternal imagination is already at work in the book of Genesis, carrying us from the murderous sibling rivalry of Cain and Abel, through the tensions between Isaac and Ishmael, Esau and Jacob, Leah and Rachel, to Joseph’s reconciliation with his brothers. Being a brother or sister is not just a matter of biological descent but of growth into mutual responsibility, building the common home. We are taken from the Lord’s question to Cain, ‘Where is your brother Abel?’, (Genesis 4:9), to Joseph’s embrace of his brothers: “I am your brother, Joseph, whom you sold into Egypt. And now do not be distressed, or angry with yourselves, because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life’. (45.4-6) Genesis founds the existence of Israel by leading us into the triumph of fraternity over rivalry.

In Christ, Israel’s story becomes the ongoing drama of humanity. We already belong to each other but we are only at the start of imagining what this means. ‘When the last day comes, and there is sufficient light to see things as they really are, we are going to find ourselves quite surprised.’ (281).

The Pope begins with St Francis of Assisi’s proclamation of a love ‘that transcends the barriers of geography and distance’ (1). Indeed, as Laudato Si’ showed, it extends to Brother Sun and Sister Moon and the whole of creation. The thirteenth century was ripe for this imagining of universal fraternity. The old feudal hierarchies were crumbling; merchants like Francis’ father were travelling all over the known world; there were new forms of communication and a new sense of the preciousness of the individual. St. Francis and St. Dominic’s usage of the earliest Christian titles, ‘brother’ and ‘sister’, had a utopian charge, the promise of a world in which the strangers who thronged the cities would be embraced.

Fratelli Tutti addresses a society facing an equally radical imaginative challenge. In our digital planet old institutions and hierarchies have lost their authority; the future is uncertain. Just as in the time of St. Francis, the encounter of Christianity and Islam is potentially perilous. St Francis set out to meet the Sultan Malik-el-Kamil (3). Pope Francis now reaches out to the Grand Imam Ahmad Al-Tayyeb.

The dream of universal fraternity has less hold on the collective imagination than before. ‘Ancient conflicts thought long buried are breaking out anew, while instances of a myopic, extremist, resentful and aggressive nationalism are on the rise. In some countries, a concept of popular and national unity influenced by various ideologies is creating new forms of selfishness and a loss of the social sense under the guise of defending national interests.’ (11).

The Pope boldly challenges us to imagine another way of belonging to each other. He rejects today’s consecration of the absolute right to private property: ‘The Christian tradition has never recognized the right to private property as absolute or inviolable, and has stressed the social purpose of all forms of private property’ (120). Our world has become a massive shopping mall. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the fiction that everything is for sale captures the common imagination: earth, water, even human beings with the explosion of the slave trade. My body is my property, to be disposed of as I will, from conception to death. The organs of human bodies are harvested for the market.

Most strikingly Pope Francis challenges the idea, foundational to the modern nation state, that a country has an absolute right to its own resources and territory: ‘If every human being possesses an inalienable dignity, if all people are my brothers and sisters, and if the world truly belongs to everyone, then it matters little whether my neighbour was born in my country or elsewhere. My own country also shares responsibility for his or her development, although it can fulfil that responsibility in a variety of ways.’ (FT 125).

This claim is shockingly counter-cultural. It subverts a fundamental presupposition of contemporary politics. For many it will seem naive at best and disastrous at worst. How can this make sense when all over the world walls are being erected and frontiers patrolled? But the Christian imagination is born of the transformative power of Christ’s cross and resurrection. On the cross Christ ‘broke down the wall of hostility’ (Ephesians 2:14). A Paschal imagination is bound to seem ‘folly to the Gentiles’ (I Cornithians 1:23) and be rejected by many.

This does not mean that it should float in disembodied space. It requires incarnation in political structures. A new fraternal world order will need ‘to devise stronger and more efficiently organized international institutions, with functionaries who are appointed fairly by agreement among national governments, and empowered to impose sanctions. When we talk about the possibility of some form of world authority regulated by law, we need not necessarily think of a personal authority.’ (172) The United Nations must be reformed.

Similarly. in making the synodal way foundational to the government of the Church, the Pope is inviting Catholics to reimagine ourselves as a community of brothers and sisters. It is only on the basis of such a cultural transformation that the dizzy invitation of Fratelli Tutti — to embrace the foreigner as our brother and sister, a member of our household — will seem not the terrifying subversion of all that we hold dear but the way to the common home for which we long.

Never in human history have so many people been on the move, fleeing violence and war. In the West especially, the walls are manned against the immigrant and the stranger who, it is feared, will undermine our local communities, our identity, and even our safety.

How can we begin to see not menacing strangers but brothers and sisters? First of all our imaginations must be liberated from fear of difference. Every human culture is only alive if it is able fruitfully to interact with what is other. Each of us owes our individual existence to the fertile difference of male and female. If we hermetically seal ourselves against the stranger, the local cultures we cherish will die. The tree outside my window thrives because from its deepest root to the tip of its branches it is in constant live-giving exchange with the air, the soil, water and innumerable insects and bacteria. Isolation is mortifying.

It requires a leap of the imagination to see universal fraternity and local solidarity as mutually enhancing. ‘There can be no openness between peoples except on the basis of love for one’s own land, one’s own people, one’s own cultural roots. I cannot truly encounter another unless I stand on firm foundations, for it is on the basis of these that I can accept the gift the other brings and in turn offer an authentic gift of my own.’ (143)

Fruitful interaction with my unknown brother or sister is only possible if I learn to look at them with a transfigured gaze, seeing their humanity, their vulnerability and their beauty. Digital communication abstracts from our bodily particularity. Digital media expose people to ‘a gradual loss of contact with concrete reality, blocking the development of authentic interpersonal relationships. They lack the physical gestures, facial expressions, moments of silence, body language and even the smells, the trembling of hands, the blushes and perspiration that speak to us and are a part of human communication’ (43). Jesus reads each person’s face. ‘He knew what was in each person.’ (John 2.25). If we learn to gaze at each other with delight, the Pope’s radical challenge will not seem an impossible ideal but the only way of happiness.

Finally, ‘a fraternal imagination’ implies that we talk to others as brothers and sisters. The Pope understands dialogue as far more than the exchange of ideas. It is the ascetic process by which one tries to imagine what it is like to be that other person, to be formed by their culture, to experience their suffering and their joy. In a brotherly or sisterly conversation, we seek fresh words together, open an imaginative space in which barriers tumble down. This is what Aquinas calls latitudo cordis, the expansion of the heart.

Such conversations bring us beyond the exchanges which are typical of the social media, ‘the feverish exchange of opinions on social networks, frequently based on media information that is not always reliable. These exchanges are merely parallel monologues. They may attract some attention by their sharp and aggressive tone. But monologues engage no one, and their content is frequently self-serving and contradictory.’ (200)

They are also utterly unlike the political discourse of our public and political life, which incites mistrust of the other and contempt for their views. The Word of God summons us to talk and listen so that an imaginative space begins to open in which the children of the one God are at home with each other and in the divine life.

Timothy Radcliffe

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti