Maureen was imprisoned for four years. Because she was black. She was beaten and tortured and her husband was shot twice. She recounts this and in the meantime, she shows the signs that she will carry on her body forever. She speaks to us of it, even if it causes her suffering. So that she does not forget and the others too.

Maureen, her husband, and her family are among the millions of victims of the South African apartheid regime. It has been twenty-five years since the first free elections were held in 1994, and they continue on the strenuous path of memory healing and reconciliation, in which women are often at the forefront. Women find themselves at this forefront especially so in communities, where they carry out fundamental work of “intercession”, promoting processes of redemptive justice, in the wake of the work done by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. These processes require a great deal of time, effort and pain, but are indispensable for the transformation of a society deeply wounded by oppression and repression into a society founded on democracy, justice, respect for human rights and recognition of the dignity of every person. A society in which the victims can find the strength to forgive - as Nelson Mandela constantly repeated - but also not to forget.

In a Somalia devastated by war and famine, fundamentalism and ignorance, Annalena Tonelli reflected. “Oh, forgiveness, how difficult forgiveness is!” She never gave up until some young extremists killed her in October 2003. “Every day in our Anti-Tuberculosis Centre in Borama, we not only treat diseases of the body, but we work for peace, for mutual understanding, to learn together to forgive. Annalena worked a lot with women, and with them, she led “the battle every day with what keeps us slaves inside, what keeps us in the dark”. A learned expert of Somali society, she knew all too well that the fight against the oppression of the strongest and the arrogance of arms, but also against fatalism and the instrumentalisation of religion could only be fought by women. To make all men free.

Throughout Africa, women are the protagonists in many situations. They often work anonymously, and are scarcely recognized for the processes of resistance and resilience, healing and regeneration in contexts characterized by conflict and crisis, refugee camps and forced migration, climatic disasters and social injustice. Some women have succeeded in breaking through the wall of invisibility, becoming examples for others of a commitment - which demands constant renewal - for peace, justice, reconciliation and healing of the wounds of the soul on a global level.

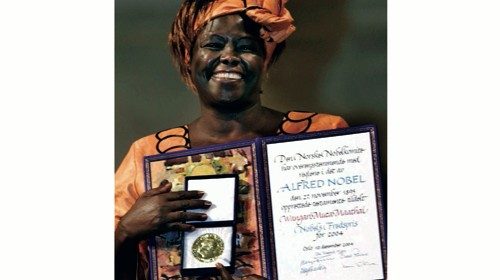

In addition, perhaps it is no coincidence that - after the South African Bishop Tutu, Mandela and De Klerk - the successive Nobel Peace Prize winners in Africa have been awarded to certain women. The first was the Kenyan Wangari Maahtai, in 2004, who was committed to the environmental and gender cause. In 2011, it was the turn of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, former president of Liberia, and her fellow citizen, the lawyer Leymah Gbowee (together with a third tenacious and courageous woman, the Yemeni Tawakkul Karman, leader of the women’s protest against the Sana’a regime). However, even Denis Mukwege’s Nobel Prize in 2018 ‘speaks’ largely female. This doctor from Bukavu received the prestigious award for his commitment to those women who had been brutally raped and abused in an attempt to destroy the social and community fabric in the eastern regions of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Peace, hope and reconciliation were also the guiding thread of Pope Francis’ trip last year to Kenya, Mozambique and Mauritius. The Pope acknowledged on several occasions the important role played by women in the processes of healing from the horrors of the past. This is not always the case, however. Even within the Church, in fact, this crucial work carried out silently by women continues to be undervalued. This is despite the fact that several official documents repeatedly stress the centrality and inescapability of women’s commitment in these areas. We read, for example, in Africae Munus, the Exhortation published after the Second Special Synod for Africa in 2009: “When peace is under threat, when justice is flouted, when poverty increases, you stand up to defend human dignity, the family and the values of religion”.

These words echo what Sister Elena Balatti, a Combonian missionary in South Sudan, has experienced personally for many years, and with the people with whom she shares her mission. She lived through the most terrible moments of the civil war in this Country, remaining in Malakal, one of the cities most devastated by the clashes, also because it is located in one of the richest regions for oil. Alongside this dramatic experience and resistance, especially with women, Sister Elena teaches Memory Healing at the Catholic University of South Sudan and is a member of the Combonian Justice and Peace Commission. Sister Elena states, “it is not enough to put an end to hostilities, even if this is an absolute and urgent priority - says the missionary - after all these years of clashes and violence, which often also affect the communities, often pitted against each other, it is necessary to accompany the population on a real path of reconciliation, valuing in particular the role of women who are the authentic artisans of peace”.

At the other end of Africa, in Guinea Bissau, Sr. Alessandra Bonfanti, of the Missionaries of the Immaculate Conception, remembers how, at the outbreak of the civil war in 1998, a women’s organization called the Peace Army was founded. This organization was made up of women who had decided to fight to bring an end to the conflict; and, who proposed themselves as mediators and contrasted the strength of their ideas with the violence of weapons. They said, “Peace is a strange animal: sometimes it hides under bombs, but we are willing to go and get it there too”.

In 2013, after the last coup d’état, a group of women from different social, economic, intellectual and cultural backgrounds met to carry out an in-depth study of the country’s situation and to develop “a women’s vision of the peace consolidation process. The Guinea Bissau we want is a country of justice and stability”, they said. “These examples – as Sister Alessandra states - show what impact women can have in the peace process. However, it is essential that they can actively participate in the social and political life of their Countries. A woman is an instrument of reconciliation that commences with her family: as a mother, bride and sister she has a strong influence on education. In Africa, thank God, there is still a heart beating for peace. A woman’s heart”.

by Anna Pozzi

It happened in South Africa

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in South Africa in 1995 after the end of apartheid and chaired by Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The name of the tribunal (with the word “reconciliation”) was in line with Nelson Mandela’s non-violent position, and who chose to heal South Africa’s wounds through the construction of a dialogue between victims and perpetrators, as opposed to the paradigm of “justice of the victors”, or the international criminal court, which is often exclusively oriented to punishing the guilty.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti