Whichever position one assumes, wanting to argue about Africa, the many Africas, its women, its peoples, and so on, risks being reiterative. As if everything has already been said. The cliché is more or less always the same, and even after doing mental somersaults, the imaginary is immobile and no longer absorbs anything that it is unable to reflect, a priori, the millenary preclusions of any innovation. Yet, of Africa, it was once said: Ex Africa semper aliquid novi!

A few years ago a journalist, who had made Africa the passion of her life, came to say that the theme “Africa” was no longer selling, no longer the current trend on the market. How shortsighted! Above all, what a void of memory, after all with the statistics to hand, we must recall that 80% of the well-being of the (so-called) north of the world comes from Africa.

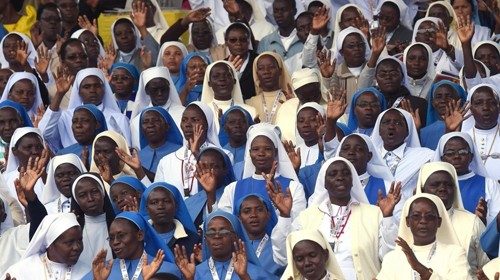

Confronted with the request made by Women Church World to have our say, we were confronted with two alternatives: we either decline the invitation, or try to narrate the becoming of this part of the world, while focusing the story on the Church, the Africas, and Women. This is a real gamble, but for years, in our own small way, we have been trying to unhinge stereotypes, to decolonize ways of seeing and minds, and thus accompany another narration of this immense heart-shaped continent. We have therefore chosen the second alternative, with a due premise, whether it is sung or not, the African ecclesial liturgy can never be without its women, for they are the vertebrae that sustains and cares for the becoming of every aspect of life.

Africa: part of the world

Whether we talk about Africa, or more elegantly about Africas, this continent is a world apart for the collective imagination. This is not how the women and men who were born in this land should be perceived.

Africa is not a world apart, but part of the world. Moreover, what happens in every part of the world, for better or for worse, also happens in Africa. Full stop. This also applies to the problem of the woman-church relationship, about which we want to talk.

Africa-woman-Church: a history to be rewritten

A great daughter of Africa, the Malian Aminata Traoré, wrote: “If you feel like a beggar, you act like a beggar. To recover our future, the first thing to do is to decolonize our spirits”. To do this, we must rewrite history, but this time it should be those who have been considered the defeated, or the women defeated, in this case.

For too long Africa has been present in society as the one who listens with no right to speak or to reply.

This is also the case in the Church. The path of evangelization in Africa has not always taken into account the life of its peoples as the sacred place that has consistently been uninhabited by God. Too often, the cultures, beliefs and spirituality of the peoples of Africa have been neglected as the good soil on which to grow the luxuriant plant of the Gospel. In the worst-case scenario, the soil has been rendered a tabula rasa; otherwise, it has been stratified, sewn with seeds from other lands. This approach has favored the all too often unconscious and profound dichotomy between the life that has been lived, in the domestic furrow of the African Traditional Religion, and the Good News of Jesus, which has often been presented by a multitude of Churches that are divided and even opposed to each other.

The continent may be considered a “lung of spirituality” - which is how Pope Benedict XVI defined Africa at the opening of the second Special Assembly for Africa of the Synod of Bishops on 4 October 2009. Instead, today we find ourselves where the percentage of Christians is very high, but the message of liberation that is the Good News struggles to find full citizenship in the daily lives of millions of women and men.

The experience of the transformation inherent in the Christian message has been extraordinarily and vividly received in the liturgies. Here the hours are not counted in the celebration of the beauty of believing; instead, too many people, upon emerging from warm and colorful celebrations, find themselves experiencing marginality, impoverishment, and unspeakable injustice that profoundly offend human dignity, and the truth of the Gospel.

Moreover, it seems to us that the Church in Africa, and therefore the universal Church, still lacks a founding narrative, i.e. the unpublished stories of men and women who have been able to transform the message of Christ into a living experience. These women and men pay dearly for their existence for their crystal clear testimony of the values of the Gospel.

We know this all too well. There are men and women who have given us pages of courageous reflection upon which to reflect, an African theology capable of touching the core of the soul of its peoples. This singular literature celebrates the meaning and flow of the many seasons of life and the events that accompany it with exemplary clarity.

Yet still too little is known. We would like to know, for example, the type of bibliography used in African seminaries or religious formation houses. If there is inefficient courage to bring them closer to the living source of their roots and cultures, what new generation can arise from the places that mark the path of faith in a Christian community? Even with the best of intentions, continuing to lend, to give knowledge, material projects, ideas, concepts, theologies, and holiness only reinforces the stereotype of Africa as a container that only receives. Therefore, history has to be rewritten. There are already, thank God, important volumes; however, one must have the courage to read them, to share them, to appropriate them, to divulge them. A few years ago, when the wind of intolerance was already strong and different boundaries were beginning to be entrenched, Lilian Thuram, a French footballer born in Guadeloupe, wrote the book Mes Etoiles Noires: De Lucy a Barack Obama [My Black Stars, from Lucy to Barack Obama]. In the preface, he wrote, “During my childhood I was shown many stars. I admired them, dreamt of them: Socrates, Baudelaire, Einstein, and General De Gaulle. But nobody ever told me about the black stars... I knew nothing about my ancestors”. And so he took up the challenge with both hands, and went to find approximately fifty men and women in that immense firmament, those black stars who were unknown to him.

Thinking back over the history of the Continent, and in particular to the history of the Church in Africa, we are already lagging behind the narration of the development of the Christian experience and its impact on African society. This narration commences with the men and the women, both young and old, who over the centuries have traced the African way to holiness. When browsing through either liturgical calendars or universal martyrology it would seem that for African female and male saints the crime of clandestinity also applies in Paradise! Without forgetting that a narrative of the faith that speaks holistically about discipleship in the footsteps of the Nazarene is now necessary.

If we say that for too many centuries Africa has been looked down on from above is not a question of over sensitivity, but a duty to justice and truth. Be brave, then, women of Africa who read these pages. Together we must have the courage to point to the black stars that illuminate the firmament of the universal Church, because, and here borrowing Thuran’s words once again “people need stars to be able to orient themselves, they need models to build self-esteem, to change their imagination, to break the prejudices they project onto themselves and onto others”.

A Synod listening to women

In the General Audience of February 14, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI said, “Without the generous contribution of many women, the history of Christianity would have developed very differently. This is why, as my venerable and dear Predecessor John Paul II wrote in his Apostolic Letter Mulieris Dignitatem: "The Church gives thanks for each and every woman. The Church gives thanks for all the manifestations of the feminine "genius' which have appeared in the course of history, in the midst of all peoples and nations; she gives thanks for all the charisms which the Holy Spirit distributes to women in the history of the People of God, for all the victories which she owes to their faith, hope and charity: she gives thanks for all the fruits of feminine holiness”.

We dare to suggest that it would not only have been the history of Christianity, but the whole history of salvation, from the first Eve to the Woman of Revelation, that would have been a different story without the presence and contribution of women

In the two Special Assemblies of the Synod of Bishops for Africa (1994 and 2009), the role of women in the Church was discussed. Proposals, promises, and many endless small steps emerged, but nothing compared to the expectations held in the hearts of Christian communities and the women therein.

Certainly, the Synods are privileged platforms and areopagos that the Pope convenes to listen, to know, to share and to illuminate the steps of the Church in the sign of synodality. However, if the question of how to start a dialogue that is open to the question of women is genuine in the Church (we certainly do not identify ourselves as “an issue”), we have to say, why not, at a future Synod, let women speak to the Pope? To tell, to explain, and collectively indicate the ways to follow for their greater involvement within and in favor of the whole Church? It would be extraordinary to be able to do this perhaps while talking about the Church of Africa!

The journey of Pope Francis to Central Africa to open the Holy Door on the occasion of the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy, was a clear example of closeness to the suffering and hope of a people that has suffered the consequences of multiple tensions and endless uncertainties for too long.

Do not be afraid to mention the woman

To speak adequately about Africa, the Church, and the women who support this continent on their shoulders -including the Church-, we need to shift our way of looking, the tone of our voice, and above all our language, which always denotes a mindset.

How sad to hear certain ordained ministers address consecrated women as if they were speaking to children to be educated and accompanied by others. Thus, speaking of Africa, its peoples, its women, consecrated women, to hear phrases such as “these Churches are (always) too young”; “they still have so much need there”; “they are not ready yet”; “they will never do what we have done”. This denotes the mentality of those who observe this Continent with an ill-concealed sense of superiority, and who considers these peoples more like victims than interlocutors.

Yet, women in Africa are not there waiting for someone to go and save them. Since time immemorial, women in Africa have walked barefoot and carried the continent on their shoulders (including the Church). It is they who have taken care of humanity, and who pay with their lives for the lives of others. It is they who preserve and transmit the faith. Looking at them with unblinkered eyes, it would seem as if they are wrapped in an invisible thread that holds them all together. It seems as if every morning you feel the warm embrace of these millions of female hands that support, caress and cradle the wounded humanity of the peoples of Africa.

The question of language, which is rarely considered and often underestimated, has, in our opinion, a relevant importance. The Church, and especially men in the Church, must learn to name us and not imply us. It is not merely an exercise in syntax when we try to use, and demand, inclusive language. The problem is that by not including us in its discourses the Church makes us invisible, even to ourselves.

During the second Special Assembly of the Synod of Bishops for Africa, in which one of us participated as an auditor (Sister Elisa, ed.) we hoped that the bishops would address women in a new way and call them “Beloved Sisters and Mothers of Africa”. And, we also suggested what to say to us, “we address you as children first of all: because you are the educators of peace, harmony and reconciliation. We ask you today to walk with us through the process of rebirth, of healing, of justice for our Africa. You, who have always walked our roads every morning and know them millimeter by millimeter, will guide us and show us which paths to choose, so as not to get lost in the meanderings of endless speeches. We entrust the present and the future of nations to you”.

Eleven years have passed since that Synod, and the women of Africa are still waiting to be questioned and included. In the meantime, a silent host of Christian communities continues to bear witness to the Gospel, the “Good News” woven into the flesh and daily life of the continent that welcomed Jesus, a refugee in Egypt, and helped him to carry the Cross, in Simon, originally from Cyrene, “encountered on the way” (cf. Matthew 27:32).

However, let us not lose hope. After all, it was to us women who were the first to receive the announcement of the Resurrection!

Vocations

While in the rest of the world the shortage of vocations is already causing side effects (ageing, huge empty buildings, immense generation gap), in Africa for years the consecrated life of women, and not only, has found fertile ground on which to grow and expand. Yet among the corridors of ancient founding Institutes, this vivacity is not always seen very sympathetically.

Here too the usual rhetoric: “but are these vocations true? They come to us to feel better, certainly to study”. Commonplaces, of course, but they hurt. The ministerial and religious vocations that arise in Africa are a gift that God gives to the Church, for the good of the whole Church and humanity. Certainly, discernment is always necessary, in Africa as everywhere else.

African religious life is having a profound impact on the life of the Church and society. The words of Sister Giuseppina Tresoldi, (a Combonian missionary who for years followed, on behalf of the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life, the journey of religious women in Africa) are significant. “They enter the social fabric and the Church and bring transformation by working in the vital sectors of education, health care and Christian formation of the people. The potential for religious life in Africa is beyond discussion. It remains a great challenge for every Congregation and diocesan bishop to channel the richness of the different charisms and ministries within the Church for its growth and sanctification, to make its African face stand out.” Hence the appeal to bishops to look at the consecrated life of women with more equity and respect, and not to think only of seminaries and the formation of priests, but to give equal opportunities for professional formation also to religious and lay women. To qualify their ministry and benefit from their experience.

Appeal to women

The Religious and women living in every corner of Africa -as in other countries of the world- must have the courage to ask that the Church look at them with the eyes of Jesus, who knew how to recognize in women a loyal co-protagonist of his Paschal Mystery and demand the space that is ours within the places where decisions concerning our own life and the life of our communities are voted on: human, of faith, of cultural belonging. They must be present in the paths that provide for the holistic formation of the person, not only within projects for human development, but also within the Seminaries, because they broaden the vision of the woman not only understood as a mother, sister, cook, etc.; but, as a student, teacher, theologian, professional. Moreover, to demand more of the urgency of our ecclesial co-responsibility, not as an exception but to become customary.

This is not an easy path, we know. However, in the footsteps of the countless Mothers of Africa, the younger generations are invited to share the courage of resilience. Or better still of resistance; because, it better expresses the fatigue, pride and stubbornness that African women have in common. Women who resist so that their peoples may exist. In addition, to regain possession of those ancient roots of history, which honors Africa not only as the cradle of humanity, but also as the guardian of the Earth where we have all learned to look to Heaven.

by Elisa Kidanè* and Maria Teresa Ratti**

* Elisa Kidanè is a Combonian missionary. Born in Eritrea, she carried out her mission in Ecuador, Peru and Costa Rica, then in Italy as a journalist in Comboni magazines. In 2009 she participated in the second Synod for Africa.

** Maria Teresa Ratti is a Combonian missionary and has lived in Kenya for 17 years. As a journalist, she wrote for the magazine “New People” in Nairobi and was director of “Raggio-Combonifem” - the magazine of her congregation - from 2006 to 2011.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti