The great mystic of Avila, a simple woman and a writer...

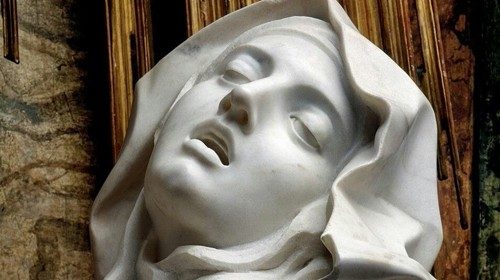

The church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome is home to the monumental marble group depicting the transverberation of St Teresa of Avila. The sculpture has attracted me more than once with its strength, and standing before it one experiences a phenomena to which we have to surrender, and admit that not even at the hundredth vision, not even after a thousand explorations will I get a sense of satiety from it. In Rome, in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria the monumental marble group depicting the transverberation of St Teresa of Avila has attracted me more than once with its strength. When I saw Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work for the first time, the two most appropriate words to describe the lava currents that I felt flowing within me were bewilderment and mystery, and which were indistinguishable from each other. I had never been in the Santa Maria della Vittoria church before, and this was the first of subsequent visits. I cannot remember how long I had been living in Rome, probably months, not years. Teresa was the name of a lady who was then approaching seventy years of age and to whom I was becoming increasingly attached every day. Her religiosity was archaic and simple, and I was ashamed every time she looked at me and asked me about mine; I did not know how to answer, and I told her how I had just recently been confirmed, as if the passage of the sacrament was in itself a screen to my life, a shelter from further questions. Alternatively, I answered her with an impossible invitation: would you like to come with me to see the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa? She would shake her head, for she always had something to do, whether it was cooking for her husband, her children or grandson, going to the doctor, or it was just too hot or too cold to go out.

Since Teresa died five years ago, I have not been back to see Bernini’s statue. I liked the fact that it was called “transverberation” so much so that I repeated the word to myself several times, for the pleasure of correcting myself, which until just before then I would have used the term “ecstasy” as a synonym. The fact that there was an angel piercing the saint changed everything, for the restlessness of the scene is the conflict. I was wondering about these things amongst others, while imagining to destroy everything with a hammer, to stop the pain disintegrating the evidence. I could not. Not only because I would have to destroy a masterpiece (Bernini, pleased with his work, described it as his “least bad work”, the best, in short), but also because my fury would have meant interrupting the experience of pleasure. Teresa of Avila wrote: “One day an angel appeared to me, who was beautiful beyond all measure. I saw in his hand a long spear at the end of which there seemed to be a point of fire. This seemed to strike me several times in my heart, so much so that it penetrated inside me. The pain was so real that I moaned several times aloud, but it was so sweet that I could not wish to be rid of it. No earthly joy can give such contentment. When the angel drew his spear, I was left with a great love for God”.

What about me, did I want to take the mystique away from a mystic?

It was Bernini’s work that got me interested in Teresa, and which made me return and read about who she was and what steps she had taken. Recently, I spoke to the writer, Dacia Maraini, about the writing of mystics, and then I read the words of Luisa Muraro, the philosopher. On the subject of Teresa’s life, a life spent fighting against the exclusion of the feminine from the divine, Muraro writes: “Despite everything, I think that women were better off than men. They have locked themselves in a cage from which they find it hard to get out, but women have been able to cultivate a more personal and fluid relationship with the divine”.

With this certainty, we enter 17th century Spain. Teresa, who was born into a wealthy family, and the granddaughter of a marrano, spent her childhood reading chivalric novels, a passion she had inherited from her mother. When she was thirteen years old, her mother died, but literature remained. It is at this time that Teresa convinced her brother to write with her one of those books that her mother would have liked (does not writing a novel mean writing a love letter to someone who is no longer there?). For an orphan with a determined and strong character, life with her father was by no means simple. In fact, Teresa ran away from home to a convent and fell ill with a terrible sickness, and from which she would never fully recover. Throughout her life, she continued to suffer from tinnitus, migraines, heart and stomach pains.

When she was sick, she could barely move her fingers. She crawled within, notwithstanding her paralysis, while her body became a prison, her ecstatic experiences began. She spoke of how they could be catalogued in seven degrees, in seven rooms, as an ascent on seven levels, the union with God was actually a movement of God inside her heart. She became “Teresa of Jesus” after the encounter with him (who are you, he asked her, and she replied; “Teresa of Jesus” “and I Jesus of Teresa”), and to whom an infinite number of biographies could be dedicated and explore how possessed she was with the deepest love, and who began to keep her visions hidden so as not to give too much of herself away to others, so as not to be corrupted by the morbidity of other people’s gaze. One of these biographies resembles a travel novel, for when she was asked to reform the Carmelite order, she moved everywhere to establish new monasteries, and between 1567 and 1571 reformed convents were founded in Medina del Campo, Malagón, Valladolid, Toledo, Salamanca, Alba de Tormes. When Teresa’s earthly body died, each monastery claimed a relic - so she continued to travel even after she had stopped breathing.

(The Teresa I knew rests in the small cemetery of her hometown. For a long time her tomb was temporary, a heap of earth; today a plant with pink flowers covers the marble).

The other Teresa was frightened at first by her dialogue with Jesus, by his apparitions, to the point of consulting exorcists and priests to confirm that it was He and not the devil. Could a woman trust herself and have more certainties on her own than a confirmation from a male world? And again: could this question of mine be read as a distortion, a forcing of a contemplative life that my small and rational mind cannot grasp? Where do I start and Teresa ends? The distance of the narrator from the narrated object is to be measured continuously, just once is never conclusive. Luisa Muraro goes on to writes, “This is what it is about and not a mere claim for equality and inclusion in the world of men: unraveling the cages of clericalism and moralism, overcoming nihilism with trust and love, making the (holy) spirit of (feminine) freedom circulate everywhere”.

A nonchalant and diplomatic Teresa led the opening of monasteries and then administered them. She was an extreme and a driving force, mad with love and lucid in her choices. Teresa tried to convince her sisters to eat more, and not to fall ill with consumption if by chance they had mystical experiences. Teresa minimized, she seemed to suffer in spite of herself, she did not boast of her uniqueness - Teresa became the first woman Doctor of the Church, in 1970. Teresa is above all a writer, and with the literary word, she bore witness to her life and offered her readers the mystery and bewilderment from hers. She used it in her autobiography and in her epistolary.

Here we can find, among other things, a manifesto of inclusion: “The holier you are, the more affable you must be to your sisters, and never run away from them, even if their conversations are boring and impertinent [...] If you want to attract their love and do them good, you must be aware of any rusticity”. For Teresa, one must live by inducing in others the desire to emulate. To be a good sister, the others must see in you what they would like to be, she says. Only in this way, can you tolerate living, and making mistakes when too much love, too much perfection, distances you from forgiveness. “[…] I accepted your apology. Since you love me as much as I love you, I forgive you the past and the future, because the greatest reproach I have for you is that you did not enjoy being with me very much, and I can see that you are not to blame... Believe me that I love you very much, and since I see this will, what is most important / the rest is nonsense that is not worthy of note.”

Once, the Teresa I met told me that she responded to any discourtesy by “letting it go.” I was too young to understand the strength of that sentence, I interpreted it as a weakness and I was angry. I thought that I did not want to become an adult like her, that I would always fight my own battles in my own way and never let anything pass that I felt was not wholesome. Fifteen years later, I now know she was right, and at my feet I see a great carpet of “unworthy nonsense.” I have changed my mind about almost everything since then, except one thing: I have almost nothing to offer anyone but what I write. This article is my love letter to that Teresa: it is not a chivalrous novel, and it was written as the substitute for a visit I never made to Santa Maria della Vittoria.

by Nadia Terranova

Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada

Born Avila, March 28, 1515

Died Alba de Tormes, during the night of October 14 and 15, 1582

Venerated by the Catholic Church and the Anglican Church

Beatification April 24, 1614 by Pope Paul V

Canonization March 2, 1622 by Pope Gregory XV

Anniversary October 15

Doctor of the Church September 27, 1970

Patroness of Spain and Croatia

The author

Born in Messina, she has written the novels “Gli anni al contrario” [The Years In Reverse] (Einaudi Stile Libero, 2015, Premio Bagutta Opera prima) and “Addio fantasmi” [Goodbye Ghosts] (Einaudi Stile Libero, 2018, finalist Premio Strega 2019). In the field of literature for children and teenagers, she has published “Bruno il bambino che imparò a volare” [Bruno the child who learned to fly] (Orecchio Acerbo, 2012), “Le nuvole per terra” [Clouds on the ground] (Einaudi Ragazzi, 2015), “Casca il mondo” [The world is falling] (Mondadori, 2016) and “Omero è stato qui” [Homer was here] (Bompiani, 2019). In 2020, she has published “Come una storia d'amore” [Like a love story] (Giulio Perrone Editore), short stories dedicated to Rome.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti