Those who cross the border into the USA receive help from Las Patronas, the women of the Romero family

“In Córdoba, Veracruz/the beautiful patrons/ brave butterflies/ give light to the migrant”, says the corrido, one of the many folk songs dedicated to the “brave butterflies” of Guadalupe or La Patrona, a tiny village of three thousand inhabitants in the municipality of Amatlán de los Reyes, ninety kilometers from the port of Veracruz. There, surrounded by sugar cane and coffee fields, is the large, Spartan home of the Romero family. In the kitchen, with its exposed brickwork, the long wooden table, the dark pots and pans, is the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe - The Patroness, from whom the community takes its name. It is here, where twenty-five years ago, Leónida Vazquez, her four daughters and seven grandchildren and their neighbors began to prepare food rations for the hundreds of migrants fleeing the violence and misery of Central America, clinging to the back of the Beast.

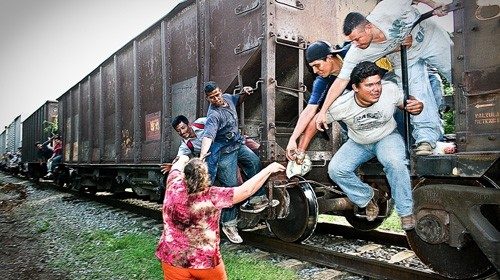

This is how the battered freight train that crosses the country from south to north to the border with the United States is known in Mexico. Grain, cement, bricks for exportation travel shut up in metal compartments. The migrants cling to the roof, or are wedged between the wagons. They have no other choice than to reach La Línea, the 3,200 kilometers stretch of border that unites or separate - depending on political convenience - the two Americas. The door, a third of which is closed by the US ElDorado’s high-tech wall. On the buses they risk being intercepted by the police and, in the best case scenario, are sent back, as undocumented migrants. Even on the Beast, in theory, they risk being caught as they travel. In fact, however, the drivers and railroad authorities turn a blind eye or do so after being bribed. And, in this way, the Central Americans advance in an endless gymkhana that lasts at least a couple of weeks. There is no direct route from Chiapas to Rio Bravo. The various locomotives alternate on the spider web of the tracks in journeys of ten to twelve hours, interspersed with breaks of two, three, even seven days, in which the migrants become easy prey for the criminal groups which control the territory. A few manage to save a few pennies for food and water. Hunger and thirst are oppressive travel companions in their Calvary to the United States.

On February 7, 1995, a group of exhausted migrants, while waiting to leave Guadalupe-La Patrona, came across the Romero sisters. Rosa and Bernarda were returning from the emporium with a bag full of freshly baked bread and milk. Huddled along the tracks, there were hundreds and hundreds of dirty, ragged, and hungry human beings. A customary spectacle for the people of the community. That day, however, three boys looked up. Their eyes crossed those of the two women. It was a moment, an eternity! “Please give us something. We haven’t eaten in days”. Rosa and Bernarda returned home without bread or milk and with a deep sense of anguish. They immediately told the rest of the family what had happened. “You have done well, my daughters, you have done well - mother Leónida whispered as she embraced them - the Virgin of Guadalupe will be happy: but we must do more”.

“They're called the flies, because they travel clung to the train like insects. But they’re not flies. They are human beings, like me”, says Norma Romero, another of Leónida’s daughter, and the best known of the twelve butterflies which tame the Beast. “I wish I was. I could fly and distribute the food bags to all the migrants on the train. I’m just a peasant girl, humble but lucky. God has given me a family, a job in the fields thanks to which I can get food without being forced to migrate. And many, many children besides my Jafet”. Norma, with her calloused hands, and long dark hair gathered in a ponytail and Rosary around her neck, says she considers the thousands and thousands to whom she has given food and water in the last quarter of a century. Her call, however, did not arrive that February 7. “It happened a year or two later. I was already helping my mother and sisters with the distribution. It’s not easy, as not all the drivers decrease speed when they see us. You have to throw the bag as quickly as possible and have the next one ready. One night, I was too slow. And one guy couldn’t catch it. Trying to hold on, he had lost his balance as he leaned out. Two of his mates grabbed him by the shoulders. The young and dark-skinned boy was hovering there for I don't know how long, with his body and arms outstretched, like Jesus on the Cross. Then, I understood, the Lord was really that prostrate, offended, and rejected by everyone. I said to myself: “Virgin of Guadalupe, from now on I will learn how to recognize your Son in the bodies of migrants”.

It is the certainty of serving Jesus that pushes Norma and the other eleven Patrons, as they have been renamed, every day, between 9 and 10 p.m., to load rations of rice, beans, tortillas (corn fritters) and bottles of water into rucksacks and bags. They make their way to the tracks, and wait for the whistle of the Beast. “By now we are organized. Sister Maria de los Ángeles calls us from Tierra Blanca as soon as she sees the locomotive passing by. We know that after about three hours it will come to us. The nun also tells us how many migrants are on board to regulate the portions”. For ten years, in addition to distributing food, the Patronas have opened a small shelter for those who want to refresh themselves before continuing their journey. “It was a little house that my father gave me. We adapted it. By what means? The same way we get food for the migrants. We put in what we can. Providence takes care of the rest. We have no fixed contributions, we are not even an association: we only receive offers from those who want to help us. Luckily there are many of them. There are also many who criticize us. They say that we are accomplices of the traffickers, that we feed the criminals, as if migrating was a fault and not a necessity. We don’t pay too much attention to it and move on. For how long? As long as the Virgin of Guadalupe wants. Without her, the Patronas wouldn’t be here”.

By Lucia Capuzzi

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti