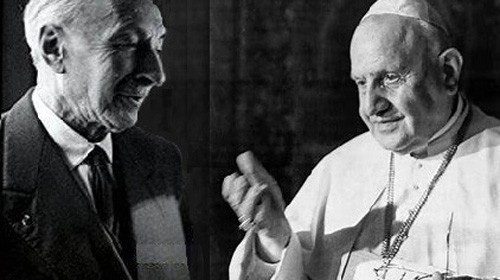

There are moments in history that change peoples and individuals forever. Many such moments are encounters between people and God or between people and their neighbors. Abraham’s encounter with the Creator in which he heard the command: “Go” (Genesis 12:1) and Moses’ encounter with God in the burning bush (Exodus 3) are two biblical examples of very transformative conversations. Another turning point in history occurred 60 years ago, on 13 June 1960, when Prof. Jules Isaac had an audience with Saint Pope John xxiii.

Fifteen years had passed since the end of the Second World War; a new world was coming into being on the ruins and devastation left by the conflagration. The Pope realized that the Catholic Church had to adapt to this new reality if it were to contribute to global needs. Therefore, on 24 January 1960, he announced that he would convene a great council of all the world’s bishops, the Second Vatican Council.

At the Vatican’s invitation, thousands of proposals were sent by bishops and theologians for possible topics to be considered by the Council. There were hardly any requests that the Council take up the question of the Shoah and its relation to centuries of anti-Jewish Christian teaching. One exception was an appeal sent by the rector and Jesuit faculty of the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome.

The evident widespread failure to understand the urgency of the question greatly distressed Paulist Father Thomas F. Stransky, a staff member of the Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity, who recalled decades later:

I asked myself: Was such indifference an unintentional collective oversight? Was the genocide experience of the Jews in Christian Europe, the “final solution” for the world’s Jewish people, already forgotten or so marginalized? Were the heavily publicized Nuremberg War Trials in 1947 a quickly extinguished blimp?

The Jewish historian, Prof. Jules Isaac was famous before World War ii for his books on secondary education in France. Although he lost his wife, daughter and son-in-law in Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, he did not become embittered. In 1947 he published an important study, Jésus et Israël on how the Jewishness of Jesus contrasted with later Christian anti-Jewish teachings. He also was one of the founders of the Amitié Judéo-Chrétienne de France and one of the key participants in the famous Seelisberg Conference (1947). He understood that although Nazi anti-Semitism had pagan roots, centuries of the Christian “teaching of contempt” (the title of his 1962 book) had served the Nazis well. And so he became one of the great advocates of Christian-Jewish dialogue. When the newly elected John xxiii announced the Great Council, Isaac sought an audience. He would find the new Pope to be a sympathetic listener.

As Ambassador of the Holy See to Turkey, the former Angelo Roncalli had provided, at the request of the Jewish Agency, thousands of false baptismal certificates and travel visas to Bulgarian, Romanian, Slovakian and Hungarian Jews, saving them from the Shoah and enabling them to flee from Europe to Palestine. On his first Good Friday as Pope, he had removed the word “perfidious” from the intercession for Jews.

When the two met on 13 June 1960, Isaac presented a portfolio that summarized his research and requested that in preparation for the Council a sub-committee examine Catholic teaching about Jews. According to Isaac, the Pope said, “I thought of that at the beginning of our conversation”. They parted amicably and when Isaac wondered aloud if he could “take away a glimmer of hope”, Pope John exclaimed, “You are entitled to more than a hope!”.

After the summer hiatus, the Pope instructed Cardinal Augustin Bea to form the sub-committee. This directive would ultimately lead to the promulgation of Nostra Aetate on 28 October 1965. John xxiii’s personal secretary, looking back at the audience with Prof. Isaac, wrote:

I remember very well that the Pope remained extremely impressed by that meeting and he talked about it with me for a long time. It is also true that until that day it had not occurred to John xxiii that the Council had to deal with the Jewish question and with anti-Semitism. But from that day on he was completely taken by it.

The brief meeting between the Pope and the Professor was thus an enormously transformative moment. It gave rise to a “journey of friendship”, as Pope Francis has described it, that has blessed Catholics and Jews ever since.

The journey has not been without missteps and controversies along the way. But gradually we have learned how to talk with each other, and in many parts of the world a profound dialogue has grown between us. We have come to treasure our differences, to cherish the distinct ways in which Jews and Christians [made a] covenant with God, to see the holiness in each other’s traditions, and to be able to say to each other, “to see your face is like seeing the face of God!” (Genesis 33:10).

As we recall the turning point in history represented by the dialogue between John xxiii and Jules Isaac, let us thank God and honour their memories by deepening and extending the dialogue they began 60 years ago.

Abraham Skorka

Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations of Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti