In his Message for the 54th World Communications Day the Pope invites people to revert to the good habit of telling stories. Telling good stories will help us not to lose our bearings. In fact, the Pope says: “we need to make our own the truth contained in good stories. Stories that build up, not tear down; stories that help us rediscover our roots and the strength needed to move forward together. Amid the cacophony of voices and messages that surround us, we need a human story that can speak of ourselves and of the beauty all around us”. To Marilynne Robinson, an accomplished writer and one of the most acute literary critics, we ask why stories are so important?

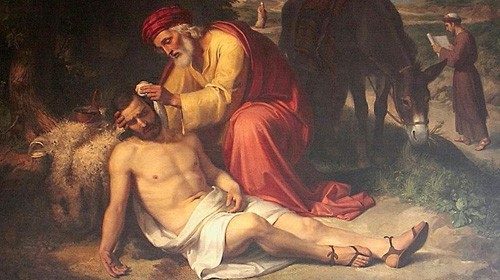

The most powerful and the purest experience I have had in my life of stories and storytelling were given to me by the books and songs my mother read and sang to me. They tended to be very, very sad — abandoned children, children who died and were bitterly and sweetly mourned, orphan children. My brother and I always wept and always begged to hear them again and again. They were, I think, a profound instruction in compassion, that deep and wholesome sorrow that children very generously suffer for a chimney sweep or a lost dog or a lame prince. Very often I have heard adults praise a book by saying it made them cry. So I tend to believe a very good book can address real fear and real pain or guilt or shame and elicit compassionate identification in the reader, which is fully as worthy as its offering him or her a world to enjoy and a model to emulate. It seems to me that compassion in the broadest sense is the life of the soul, the human analogue to divine grace. If the bitterness of a tale is compensated by the reader’s deep wish that things could be otherwise, teller and reader have created one story between them. Of course for this to be achieved the writer herself must have a compassionate and tactful understanding of the world she is making. The American philosopher C. S. Peirce said that God would be most Godlike in loving those who resemble Him least. I think harsh texts often try, and often fail, to effect an embrace of those only God and the writer could love.

In what sense do stories have to be “good”? Is it for their content? Or for the style in which they are written? Yet stories (novels, movies, newspapers) mostly tell stories which are full of evil. What relationship is there between the need to tell good stories and the presence of evil in people’s lives?

Good stories come from such a deep place in consciousness that their “goodness” arises from elements that have merged and modified one another and invited new elements drawn in by association and cultural memory — all this before the writer knows more than that a live seed of embodied thought — an “idea” — has begun to germinate. When the realization comes, then the writer must be very attentive to the nature of the story. What voice will it speak in? What language will flesh it out? A good story is a successful collaboration between the writer and the thing to be written. This quality in the work is palpable. Again, this view of the matter has no obvious implications for the value of the story in moral terms, except in one very essential way, that it is an instance of the fact that our minds are strangely and wonderfully made. We can imagine and speak at the farthest limits of our own words and understanding, and, miracle of miracles, be understood! A good story externalizes a moment in the working of a mind, and those who hear it recognize it as somehow their own.

The Pope states that telling stories allows each person to bring her or his identity into focus, to know herself or himself, and it helps one to understand reality. Does literature have a cognitive function? What is the use of literature?

I have filled my head with literature for so many years that I can hardly offer objective testimony in this matter. I do agree that narratives of all sorts — advertisements, gossip, the trashiest ephemera — do enter into our sense of ourselves and others. People are very much shaped by their expectations, by the way they expect the plot of their life to unfold, and this can make them fearful or hostile or self-seeking, even without respect to their own fortunate histories. Young writers often feel they have to be grimly loyal to this “reality” they themselves have never encountered except as a consumer product, on a television screen or in a best-seller.

On the other hand, good literature is an honest witness, attentive to the complex and mingled experience of actually being in the world. A teacher told me once that the function of literature is to reduce chaos to meaningful complexity. Patience, charity and a true reluctance to judge allow the world to present itself fully enough to allow meaning to emerge where we may not expect it, and beauty to surprise us. Insofar as we pass beyond prejudice and canard, they allow truth to set us free, or at least to loosen our chains.

The Pope thinks that telling stories is good not only for the individual, but also for the community. The community is a group of people, one could say it is a “weaving of stories”, therefore telling stories helps build a community. Does the art of storytelling have a social and political function?

History demonstrates continuously how important stories are to communities. Your three last questions are so intertwined that I will answer them together. Stories can nurse and shelter antagonisms and resentments, and writers, like politicians, have been richly rewarded for propagating destructive narratives. Many writers were notoriously supportive of Fascism in the last century, and have been revered all the same, as if they were somehow exempted from moral judgment because they were writers. Whether this is reverence or veiled contempt, or some nameless combination of the two, I cannot decide. How bizarre it is to act as if any human being could be too lofty to be subject to humane norms, or so marginal and trifling that he or she has the kind of immunity we grant to children and the incompetent. And they earn this abysmal status by writing poetry and novels, which, if they have any worth at all, should be proof of functioning intelligence. In all candor, I feel that this exemption has depleted the truth and sapped the vigor of Western intellectual culture.

When I taught young writers, my colleagues and I had a sort of motto: first, do no harm. We meant that everyone who came to us should leave us as able to write well as they were when we admitted them. Teaching of that kind is delicate work and can go very wrong. But that old oath lends itself to very broad application. Harm spreads pandemically. It is a good and beautiful discipline to honor those around us, and the faith we claim, with great, generous care.

Andrea Monda

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti