He had returned to the Vatican just a few days before his 70th birthday. I, on the other side of the ocean, was thinking about what had just taken place, a truly unique experience, humanly and spiritually “overwhelming” is how I would define it, for myself and for the millions of faithful met along the way who had practically led him to touch, in one week, the entire geography of the “land of volcanoes”.

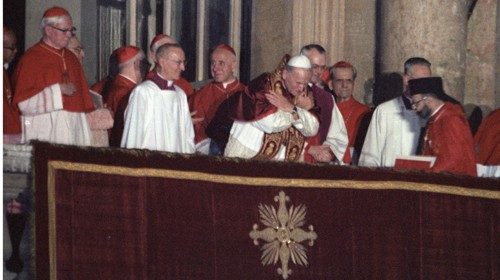

Mexico City, 1990. It was May then too. There began my most personal memories of Saint John Paul II, whom I had quickly greeted several years before during his visit to the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy. He had concluded his 47th Apostolic Journey abroad, in which I was directly involved in preparations and in which I was directly involved as Secretary of the then Apostolic Delegation to Mexico. The same country which, in January 1979, had constituted the first ring of that impossible chain of worldwide apostolic itineraries undertaken by the Pope “called from afar”, who managed to broach every distance, not just those measured in kilometres.

In those times Mexico, even while counting 95 per cent of the Catholic population, fervidly Marian due to the presence of the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in the capital and of the countless other places of worship dedicated to the Most Blessed Virgin in the entire territory, preserved a secularist Constitution, which did not recognize the Church’s right to exist, and even went so far as to prohibit religious functions in public.

But John Paul II did not come as a politician seeking accords, even if his charism and his “impetus” favoured, in the years immediately thereafter, the transformation of the Government’s policy on religious matters and the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Holy See, in favour of those for which the then Apostolic Delegate, Archbishop Girolamo Prigione, had long and tenaciously worked. Instead, he introduced himself as a pilgrim seeking faith. At the welcome ceremony in the airport he said: “The Lord, the master of history and of our destinies, has wished that my pontificate be that of a pilgrim Pope of evangelization, walking down the roads of the world, bringing to all areas the message of salvation”. Shortly afterwards he re-emphasized the concept, presenting himself as “‘pilgrim of love and hope’, with the desire to enliven the energies of Church communities, so that they might bear abundant harvests of love for Christ and service to their brothers and sisters”.

I think one could condense these words into a single one: mission. For him it was not a preferential option, but an evangelical need. To go outside of oneself in order to rediscover oneself, to lose oneself in order to find oneself: the Teacher taught this. The very name he had chosen as Pontiff bore the imprint of that of the first great missionary, Paul of Tarsus. Like him, he had received the irrepressible call to enlarge the doors of the house in order to make anyone who reached it feel at home: the house of the living God is destined for the great human family. Not only that, but as the Apostle of the Gentiles, he did not spare himself, becoming everything to everyone in order to become involved with them (cf. 1 Cor 9:23).

I was left with an indelible and inspiring impression by the effort that he made to be faithful to the two events scheduled for each day, one in the morning and one in the evening, in different parts of the Republic, with the celebrations respectively of Holy Mass and of a liturgy of the Word. And with that sense of humour that characterized him, for which one morning, in greeting as usual the tens of thousands of people who “lay siege”, day and night, to the offices of the Apostolic Nunciature during his visit, praying and singing, he said (with reference to the fact that that evening he would not return to Mexico City as he had in other days): ‘Today I am giving you a vacation: rest a little!’.

In this way that “Open the doors to Christ” made its way ever deeper within me. It was not merely a courageous exhortation, so much as the awareness that it was impossible to be Church if not truly opening the doors of the house to the Lord and, with him, to all brothers and sisters created in his image. A message given to the world immediately, from the inauguration of his Pontificate and from his first Encyclical, dedicated to the Redeemer of man and to man, through the Church.

Thus, the diplomatic service, in which I was taking my first steps, was opening up broader horizons: it required not only calling its own legitimate reasons to the attention of others, but opening — we first and then everyone — the doors of the house, in Jesus’ name. It meant living the diplomatic mission by recalling that the noun precedes and motivates the adjective. It meant welcoming a splendid truth: that of not being foreigners in any country, and thus at home everywhere. Not only because Catholics are everywhere in the world, but above all because in mankind, in every man and woman, Christ is knocking, asking that a door be opened.

Thus new gestures again flourish in memory, from the ancient evangelical zest, signs, indelible images: crossed borders, ecumenical, interreligious, social and historical encounters. A Gospel of life expressed in the singular and plural: a Gospel of many, many lives (who has encountered more in recent decades?), all precious, unique, embraced by a smile that always loved beauty, as he stood out gleaming on the cliffs of the Valle d’Aosta and as he lay, curled up and suffering, in a hospital bed. It is no coincidence that the most suffering Pope whom the media has shown us was also the Pope of young people, to whom on 15 April 1984, on the occasion of the first Day dedicated to them, he addressed a memorable phrase: “It is worthwhile being man, because you, Jesus, were man!”.

Rome, 2005. Twenty-five years had passed since those eight unforgettable days in Mexico. I too had crossed the ocean, joining the Curia in the meantime. In the Spring of that year from the open windows we saw rivers of people walking, between prayers and songs, toward the one who, introducing the Church in the third millennium, had spoken of the new springtime of the Spirit. People from everywhere came to exchange visits with the pilgrim Pope. The Christian and human family clung to its father, brother, friend. Many languages expressed the same affection for the missionary Pope who had travelled the planet to remind everyone of the dignity of each one.

In the Christian language, mission rhymes precisely with communion. The Second Vatican Council taught this, recalling that the Church, essentially, is communion itself and mission for others. The itinerant John Paul II was first a young father and then elderly son of the Council, the road map for the Church of our time. And there we were, all close in communion around the Pope of mission, in those first days of April, in its Easter days. We were looking at the Crucifix and at his cross, gathered like Mary and John at the foot of the wood, to form a family. We understood that those names suited him: Mary, whose initial stood tu out under the cross on his coat of arms, but was firmly impressed in the Totus tuus del cuore; John, the evangelist icon of communion, first name of a Pope faithful to it, as father of the entire human family. The last image is his appearance above the Square, on Easter Sunday, at the window, gesticulating and silent for the final, wordless blessing, made with his life. Someone wrote that life is an open window on the world. I think that this applies in a special way to the Pope born 100 years ago. I thank him with all my heart for having opened so many windows in my inner world as well. And for letting Light of the world enter.

Pietro Parolin

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti