«The Church would collapse without women», declared Pope Francis, with a frankness that surprised many. These strong words marked a significant turning point in what is a long and complex journey that began over sixty years ago with the 23 female auditors at the Second Vatican Council.

Today, with the election of Pope Leo XIV, the issue of women in the Church finds itself at a new potential crossroads. On the one hand, the voices of women are being increasingly heard throughout the Vatican’s corridors, with appointments that would have been unthinkable just twenty years ago. On the other hand, the question of access to the diaconate remains under scrutiny, but currently there are no prospects for change. This stasis is fueling ongoing discussions within the Church and has prompted diverging opinions among Catholic women themselves, with no clear synthesis in sight.

Religious sisters run hospitals, schools, and charitable institutions around the world, and some lead congregations as large as multinational corporations. There are increasingly more women who hold chairs in theology, who publish academic research, and shape theological thought; however, the question of their role within the Church remains a highly contested issue. This contention is a litmus test, which is revealing contrasting perspectives. Therefore, the question is, what has changed since the Second Vatican Council?

As we look back at the papacies over the past sixty years, there has been a path of gradual opening up that emerges on one hand, while accompanied by persistent resistance on the other. This contrast reflects a Church caught between tradition and renewal. This journey is characterized by doctrinal continuity as the seven popes since Vatican II have upheld the position that the priesthood is reserved for men, however, there has been practical progress, albeit slow and often hindered, in expanding opportunities for women’s participation.

The breakthrough came with Pope John XXIII, who in Pacem in Terris (1963) marked a turning point in Catholic social teaching. In this encyclical, the pope explicitly identified women’s emancipation as one of the positive «signs of the times», and in so doing, he affirmed the dignity of the human person without gender distinction. He acknowledged women’s right to working conditions suited to their needs and their roles as wives and mothers, and supported their full participation in public, social, and political life on equal footing with men.

The pontificate of Paul VI took place during a period of profound social change. This was the era when the feminist movements emerged and the demand for equal rights grew stronger. In this context, the Pope wrote in his Message to Women at the close of the Council (1965), «It is up to you to save the peace of the world!» Thus initiated the first significant dialogue on the question of women, which clearly affirmed the equal dignity of man and woman, who are both created in the image of God.

Montini, who was the Council’s most significant helmsman, began to open certain ecclesial roles to women, while maintaining a clear distinction regarding ordained ministries. He also made a symbolically important gesture by proclaiming, in 1970, the first two women Doctors of the Church; first, Saint Teresa of Ávila; and then, Saint Catherine of Siena. His approach, which was rooted in Christian tradition, placed great value on motherhood as a specific female vocation, but also recognized that a woman’s identity is not limited to it.

In the apostolic letter Inter Insigniores (1976), he reiterated the impossibility of priestly ordination for women.

With John Paul II, theological reflection on this issue became more developed. In 1988, he published the important apostolic letter Mulieris Dignitatem, in which he emphasized the complementarity between man and woman and the specific role of women in the Church and in society. In 1995, he wrote the Letter to Women, in which we read, “The Church sees in Mary the highest expression of the ‘feminine genius’”. In 1994, with his apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, he confirmed the Church’s longstanding position on male priesthood, and in so doing declared that the Church did not have the authority to confer priestly ordination on women and that this decision must be considered definitive. In 1997, he proclaimed Thérèse of Lisieux a Doctor of the Church.

Benedict XVI’s pontificate continued along the same path as his predecessor, so reaffirmed the irreplaceable value of women in the Church, while confirming traditional positions on ministerial roles. Pope Ratzinger gave prominence to female figures such as saints, theologians, and mystics, and proclaimed Hildegard of Bingen a Doctor of the Church in 2012. In his magisterium, he emphasized the complementarity between man and woman, rejected gender theories, and proposed an anthropological vision based on the natural difference between the genders.

With Pope Francis, there was a significant shift in approach that, while not changing the doctrine on ordained ministries, introduced concrete changes and opened up new perspectives. His criticism of ecclesial “machismo” and his call to “de-masculinize” the Church gave a new tone to the debate. Francis appointed laywomen to positions of responsibility that had never before been entrusted to female figures, and established two commissions on the female diaconate, which reopened theological and historical discussions on the issue. However, he was also criticized for the lack of definitive decisions in this regard. His pontificate confirmed the position on the exclusion of women from the priesthood, but it did represent an attempt to change the style of leadership and to give greater voice and space to women in the Church’s decision-making processes.

Catholic women, whose expectations have grown considerably, now experience this state of affairs with mixed feelings. There are some who appreciate the steps that have been taken, others consider them insufficient; some share the traditional view of ministerial roles, while others hope for radical changes.

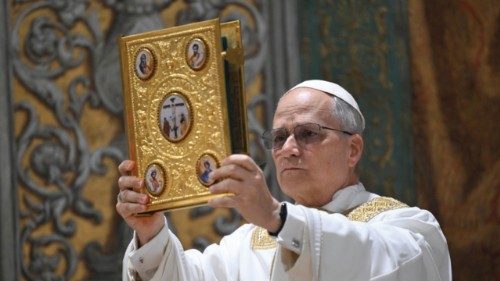

The election of Pope Leo XIV now opens a new chapter in the history of the Church. His history, his first words, his initial gestures and meetings all point to a man of dialogue, peace, and justice. Of hope. «We still see too much discord, too many wounds caused by hatred, violence, prejudice, by fear of those who are different, by an economic paradigm that exploits the Earth’s resources and marginalizes the poorest», he emphasized in the homily of the Mass inaugurating his pontificate.

But the path is «to be walked together: among ourselves, with the sister Christian Churches, with those who follow other religious paths, with those who nurture the restlessness of seeking God, with all women and men of goodwill, to build a new world where peace reigns».

His first appointment in the Curia is a woman, and a significant one, in sister Tiziana Merletti, of the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor, who he has named Secretary of the Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. The Prefect of the Dicastery is sister Simona Brambilla.

***

This month’s issue of Women Church World focuses on hope, which is the theme of this year’s Jubilee. This hope is not about passively waiting; instead, this hope is a force that drives action. It expresses the deep human need not to be manipulated, to resist, and it is the spark that allows us to imagine and build a more humane society. Those who hope do not wait for change, they are the ones who make it possible.

In this special issue, many women speak who embody this militant hope. Among them, there is Sister Norma Pimentel, the “angel of migrants” at the U.S.–Mexico border; poet Carmen Yáñez, who survived prison and torture under the Pinochet regime and who -like her husband, writer Luis Sepúlveda- has made testimony a duty and memory a weapon of justice; and Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe, who in Central Africa restores dignity and a future to former female child soldiers.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti