A council and a pontificate are two complex realities. They both make an impact on current events and bear fruit in history. Like all other pontificates, Francis’ too will be judged by history, and like all other councils, Vatican II is undergoing the scrutiny of historical judgment. This is happening more than by historians; instead, it would be better to say by the judgment of the Church living within history. We know well how laborious the reception has been over these first sixty years, of a council convened with the explicit intention of renewing the Catholic Church. At a time when the Catholic Church had truly become universal, represented at the council by bishops from every continent, who brought with them the vitality of local Churches that proclaimed and lived the faith in increasingly diverse contexts. It would not have been possible, moreover, to witness, after the Council, the succession of a Polish pope, a German one, and then an Argentinian, if the reality had not already been that of a Church whose designation as Catholic had come to coincide with the abandonment of Eurocentrism and a diaspora at the ends of the earth.

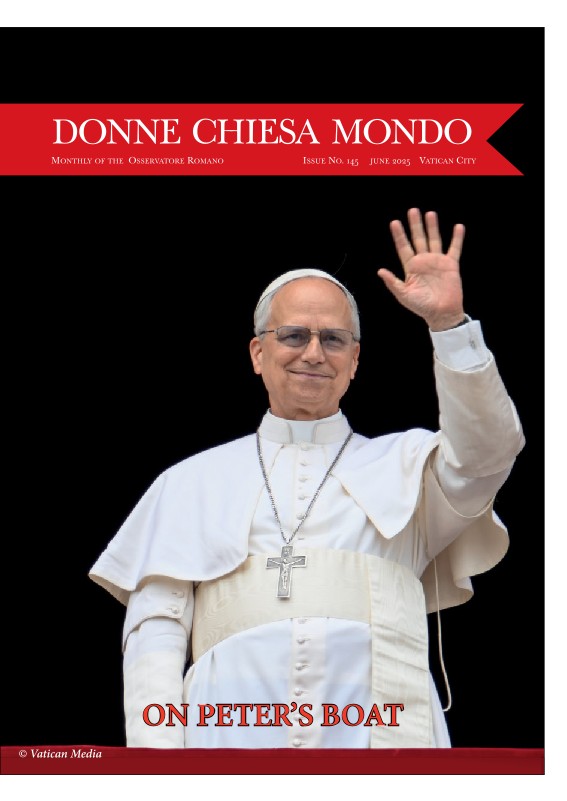

One thing is certain. From the very first days of his election, Francis made it clear that the Second Vatican Council had not happened in vain. This has to be said without exaggeration, certainly, but not without conviction. If we turn our minds back to the homily he gave during a celebration on October 11, 2022, marking sixty years since the solemn opening of that assembly which has gone down in history as a “springtime for the Church”. This was a celebration the Pope himself had desired, as he sensed the significance that the memory of the Council could and should have throughout the Jubilee year. “Let us return to the Council’s pure sources of love. Let us rediscover the Council’s passion and renew our own passion for the Council!” Sixty years later, Francis sought to pick up the thread that had triggered its climate, drawn its horizon, and established its purpose.

“Gaudet Mater Ecclesia” (“Mother Church rejoices”). With these words, John XXIII commenced his opening at the Council, and Francis echoed them, stating, “May the Church be overcome with joy. If she should fail to rejoice, she would deny her very self, for she would forget the love that begot her”. We know well that, especially in the early part of his Magisterium, Francis was not afraid to insist on joy and praise as dispositions that reveal the trustful posture with which the Church looks to God and walks through history. If we recall the titles of his first four major documents, each one points to a distinct note of joy: the joy of the Gospel (Evangelii Gaudium), the praise of God in the face of the gift of creation (Laudato Si’), the gladness of a love able to take flesh in the chiaroscuro of everyday life (Amoris Laetitia), and mercy (Misericordia et Misera). Referring to the latter, “Mercy” was a central word in the Gospel’s vocabulary that Francis placed at the heart of his pontificate. In primis, he chose mercy as his episcopal motto in the phrase with which the Venerable Bede, in a homily, comments on the calling of Levi the tax collector: Miserando atque Eligendo (Matthew 9:9: “Looking at him with mercy and choosing him”).

Recognizing God’s presence in history and being grateful for it because it is a gracious and grace-filled presence harkens back to the constitution Gaudium et spes on the Church in the contemporary world with which the Council brought the world into an almost totally clerical assembly and thus initiated that process of declericalisation that Francis understood to be the only possibility for bringing the Catholic Church out of the shallows in which it risks being stranded at the beginning of the third millennium? On the other hand, his incessant call for a Church that “is communion” and therefore does not yield “to the temptation of polarization” strongly recalls the Lumen Gentium constitution on the Church. He also said it that evening with the intensity that characterized his ecclesiology throughout his pontificate, stating, “Let us not forget that the People of God is born “extrovert” and renews its youth by self-giving”. This was the dream of the Council and has become the life program of national Churches and ecclesial communities that have not ceased to engage in building a world that is a little less unjust over the decades.

One might wonder if, precisely because he is a “man of the Council”, Pope Francis had to experience the same divisions that it brought about. Both in the Spirit and the letter of the Council he sought in every way to avoid yielding to divisions, to mediate the differences that had become inevitable in a Church spread throughout the world, and to find a language capable of preserving the great heritage of tradition without succumbing to the fear of renewal that every possible future may impose. From the Council, Pope Francis received the weighty inheritance of a Church that must confront a turning point; in other words, a Reform that asks her to rethink her past with clarity in order to understand what has to be done with a reconciled heart. To free herself from the weight of abuses of power and conscience, as well as sexual abuses, certainly, but above all, to confront a world increasingly thirsty for violence and to keep her trust firm in the strength that comes from her God and in the intrinsic goodness of the human being. In addition, to find new ways to reconcile doctrine and discipline to build a welcoming home for all.

Rightly, so, Pope Francis was convinced that the world needs the Church. We saw this during the time of the Council, when the Church testified that it could be for the world, as John XXIII liked to say, the fountain in the village square. We see it in the dark days we are living through, when only an elderly and sick pope never ceased to be the voice of a God who said, “For I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope”. (Jeremiah 29:11).

by Marinella Perroni

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti