Different Perspectives

What does Nennolina

The Basilica of Holy Cross in Jerusalem, posing at the end of the road that bears its name, is a landmark for the Spin Time occupied building, where, in 2019, Cardinal Konrad Krajewski descended into the power plant room to restore electricity. In a neighborhood that has undergone significant transformation since the 1930s and today, apart from the occupied building, is essentially a bourgeois district, the church, between Piazza di Porta Maggiore and St John Lateran, maintains its spirit of openness. On the square and then among the aisles, one can meet people of all kinds and origins; tonight, the day after Palm Sunday, a man with smiling and suspicious eyes still distributes olive branches. Boys, volunteers, elderly women come and go. At the entrance of the church, there is a blue sign that says: Relics.

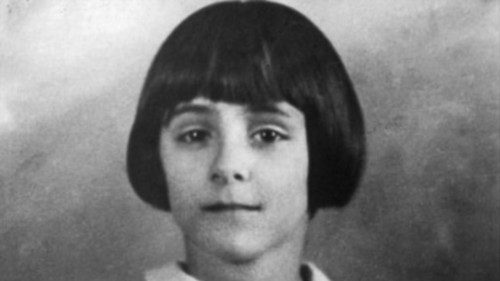

I don’t live very far away, just a few blocks east towards the outskirts, so when I found out that Holy Cross in Jerusalem was the parish of Nennolina, a venerable child who entered popular devotion with that name, I decided to come and see. Antonietta Meo, who lived for a few years from 1930 to 1937, declared venerable in 2007, is buried inside the church; there is an entire room dedicated to her relics. When I had read about relics, no light had turned on in my mind; my idea of relics and the image I had formed of that child, whose fringe and dark ironic eyes I had seen in a photo, did not match up.

I enter and walk along the left aisle, following the signs, turning left again and find myself in front of the room. The room dedicated to her is lit by soft yellow bulbs, on the walls there are four hieratic portraits, the style reminiscent of the return to order school of painting, all four seem to be taken from the same photo, the girl always wears a blue dress with small frills, there is also a dark statue representing her; candles can be lit for her. Surprised by my own gesture, I light one. In the display cases on either side of the door are her relics, toys from the 1930s, colorful tin carousels, wooden horses, illustrated postcards with smiling children, album covers: it’s a snapshot of an era, of the middle class of that time, of a childhood shared with many other girls. Nothing strange, nothing excessive, a few specifically religious items. Alongside the toys, there are notebooks, open to pages written in her own handwriting. A religious and lively girl, as she is told, who, like many others, goes to kindergarten with the nuns, who is a member of the Catholic Action, and one day falls, struggles to recover and eventually discovers she has osteosarcoma, loses her leg. A tragedy. A very tough period begins for her, with a rhetorical figure weakened by the use we can call her calvary. But she revitalizes the word, using all the means that her religious upbringing provides her, finding a way to make that climb, all that pain, into something else, not blind, not useless: like the mystics of every age she changes its meaning. She takes the pain and gives it value, makes it a means of communication with the divine, voluntarily intensifies her suffering to not be its prey and to obtain peace, and then she shows this peace to others, makes it available to those close to her, and they feel comforted by it. On the pages of her notebooks, she writes letters to Jesus. She writes very well for her age, she has just learned, her handwriting is graceful and without spelling mistakes; in the few lines I manage to read through the glass, there is no torment, only affectionate and simple thoughts. In the display case on the other side of the door, the clothes faded by time, the blue dress with frills she appears in the photo and in all the portraits, other clothes she wore, a smaller pink one. These are the clothes that allow us to imagine how small she was. Her determination, serenity, and firmness impress her family, doctors, and those around her, so the girl is entrusted to a spiritual father.

While it’s perfectly understandable that after her death devotion would grow in the neighborhood and affection would nourish devotion, it’s striking that her process was initiated thirty-one years after her death, in 1968, and that in a year very close to our own, in 2007, she was declared venerable. What does Nennolina tell us, with that endearing familiar nickname that, outside the walls of her home, becoming a venerable public name, becomes so alienating? In early Christianity, children, girls, and adolescents were canonized as martyrs at the hands of enemies of the faith; with the sanctification of Maria Goretti in 1950, the concept of martyrdom extended to include martyrdom in defense of chastity; but the twentieth century, even in its early part, sees the presence of a certain number of children who will then be beatified for their heroic virtues, among them with Antonietta Nennolina Meo there are other girls. What are their heroic virtues and how do they speak to us?

The end of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century see children’s subjectivity emerge forcefully along with its contradictions. Boys and girls become visible but lack even minimal autonomy. Instead, family education, school, and literature production demand from them responsibilities and duties towards the adult world, as if the moral fabric of the world depended on their exemplarity. It’s a demand similar to that addressed to women, to remain outside the dark conflicts of the world to ensure its emotional and moral stability, comforting and guiding the men who fight in the fray. Only, for children, and for girls to an extreme extent, the demand is radical. But the girls we are talking about carry an even greater radicalism, pushing beyond mere compliance with adult demands, finding their own paradoxical autonomy.

Twenty years before Antonietta Meo, in France, Anne de Guigné lives a privileged life in a castle in Annecy-le-Vieux. She has a legendary character, stubborn, proud, and capricious. Then her father dies in the Great War, and despair and helplessness descend into Anne’s life. One day, however, her mother makes a request: she must be good if she wants to console her. Anne finds herself awakened, as if she had found the way out she was seeking. She forces herself to become docile and obedient. In a mixture of trust and iron will, she finds her answer to helplessness, a form of action, even autonomy, in self-mastery. Her friendly conversations with Jesus alternate with attention to the poor, to the sick; she takes on the now unavoidable issue - which Teresa of Lisieux had tackled forcefully - of unbelievers, the absolute needy. In 1920, ten years before Antonietta, in yet another circumstance, Anfrosina Berardi is born in San Marco di Preturo, near L’Aquila, the daughter of farmers. Her life until the age of eleven seems like the most normal life in the world, even though, as Don Luigi Maria Epicoco says in the podcast dedicated to her, the girl has a special familiarity with religious matters, a voracious passion for prayers, a hatred of evil, even the smallest. Then illness strikes, appendicitis immobilizes her in bed and leads to her death. Her trust and ability to turn pain into an opportunity, material from which to extract meaning, reassure those who visit her. This is the form her heroism takes.

Odete Vidal Cardoso, who is the same age as Nennolina but lives in Brazil, also sees suffering as a malleable material. Even Odete, who fell ill with typhoid at the age of 8, dedicates her suffering “to missions and poor children”. Declared venerable by Pope Francis in November 2021, Odette comes from a wealthy background. The scandal she opposes is inequality; she refuses to dress in expensive clothes and spends her time with the children of domestic workers. Her role model is Thérèse of Lisieux, who showed a path to follow and made it available to girls. Antonietta, Anne,

Anfrosina, Odete, they are bound by illness and early death, of course, if not how could they be venerable little girls. For each of them, what to do with suffering is the heart around which the rest of their actions gather: how to make pain an instrument of meaning and not slip into despair. So they speak to us, even as they disturb and annoy us. Fortified by radical trust in a promise, finding themselves in the body of suffering they act with it. But even trust and redeemed suffering are not enough to protect them. Even six-year-old Nennolina prays for those supreme poor of the unbelievers, like Anne de Guigné. And like Thérèse of Lisieux for a moment she loses touch with Jesus, slips into the darkness of the soul, though then happily finds him again.

Their precision in pointing out each scandal, death, pain, the temptation of meaninglessness, inequality, is a most powerful provocation for us, for which to be grateful. But leaving the room dedicated to Antoinetta Meo I wish I had a veil capable of covering her, hiding her from the gaze, returning her to her games, the merry-go-round, the horse, the postcards.

by CAROLA SUSANI

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti