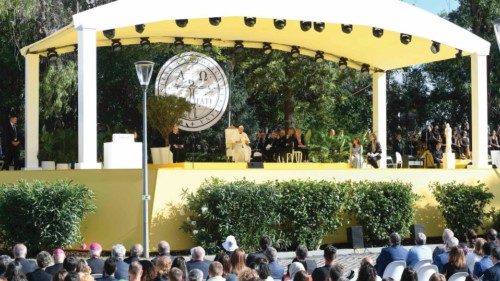

On Thursday morning, 3 August, Pope Francis met with University Students at the Catholic University of Portugal in Lisbon. He told them that “an academic degree should not be seen merely as a licence to pursue personal wellbeing, but as a mandate to work for a more just and inclusive society, a truly progressive society”. The Pope also encouraged the young men and women present to become “teachers of compassion” and of “new opportunities for our planet and its inhabitants”. The following is the English text of the Holy Father’s words.

Dear brothers and sisters,

bom dia!

Thank you, Madame Rector, for your kind words. Thank you! You said that all of us feel like “pilgrims”. That is a beautiful word, and one well worth reflecting on. To be a pilgrim literally means to put aside our daily routine and choose to set out on a different path, moving away from our comfort zone towards a new horizon of meaning. The notion of “pilgrimage” nicely describes our human condition for, like pilgrims, we find ourselves facing great questions that have no simple or immediate answers, but challenge us to continue the journey, to rise above ourselves and to press beyond the here and now. This is a process familiar to every university student, because that is how knowledge is born. It is also how spiritual journeys begin. To go on pilgrimage is to head towards a destination or seek out a goal. Yet, there is always the risk of heading off into a maze, with no goal in sight, and no way out! We are rightly wary of quick and easy answers, which can lead us into a maze; let us be wary of facile solutions that neatly resolve every issue without leaving room for deeper questions. Let us be wary! Indeed, our vigilance is a tool for helping us to move forwards instead of going round in circles. One of Jesus’ parables uses the example of a pearl of great price, which is sought and found only by the wise and resourceful, by those ready to give their all and risk everything they have in order to obtain it (cf. Mt 13:45-46). To seek and to risk: these are two words that describe the journey of pilgrims. To seek and to risk.

As Pessoa once noted, ruefully yet rightly: “To be dissatisfied is to be human” (Mensagem, “O Quinto Império”). We should not be afraid to feel somewhat ill at ease in thinking that what we are doing is not enough. Being ill at ease, in this sense and to the right degree, is a good antidote to the presumption of self-sufficiency and to narcissism. Our condition as seekers and pilgrims means that we will always be somewhat restless, for, as Jesus tells us, we are in the world, but not of the world (cf. Jn 17:15-16). We are always journeying “towards”. We are called to something higher, and we will never be able to soar unless we first take flight. We should not be alarmed, then, if we sense an inner thirst, a restless, unfulfilled longing for meaning and a future, com saudades do futuro! [Looking to the future]. And here, in addition to the saudades do futuro, do not forget to keep alive the memory of the future. We should not be lethargic, but alive! Indeed, we should only be worried when we are tempted to abandon the road ahead for a resting place that gives the illusion of comfort, or when we find ourselves replacing faces with screens, the real with the virtual, or resting content with easy answers that anesthetize us to painful and disturbing questions. Such answers can be found in any handbook on how to socialize, on how to behave well; but easy answers anesthetize us.

I would encourage you, then, to keep seeking and to be ready to take risks. At this moment in time, we are facing enormous challenges; we hear the painful plea of so many people. Indeed, we are experiencing a third world war fought piecemeal. Yet, let us find the courage to see our world not as in its death throes, but in a process of giving birth, not at the end, but at the beginning of a great new chapter of history. We need courage to think like this. So, work to bring about a new “choreography”, one that respects the “dance” of life by putting the human person at the centre. Your Rector’s words impressed me, especially when she said that “the university does not exist to preserve itself as an institution, but to respond courageously to the challenges of the present and the future”. Self-preservation is always a temptation, a knee-jerk reaction to fears that distort our view of reality. If seeds were to protect themselves, they would completely destroy their generative power and condemn all of us to starvation. If winter were to persist, we could not marvel at the spring. Have the courage, then, to replace your doubts with dreams. Replace your doubts with dreams: do not remain hostage to your fears, but set about working to realize your goals!

A university would have little use if it were simply to train the next generation to perpetuate the present global system of elitism and inequality, in which higher education is the privilege of a happy few. Unless knowledge is embraced as a responsibility, it bears little fruit. If someone who has benefited from a higher education — which nowadays in Portugal, as in the wider world, remains a privilege — makes no effort to give something in return, they have not fully appreciated the value of the gift they received. I like to recall that, in the book of Genesis, the first questions God asks are: “Where are you?” (Gen 3:9) and “Where is your brother?” (Gen 4:9). We do well to ask ourselves: Where am I? Am I trapped in my own bubble, or am I ready to take the risk of leaving my security behind and becoming a faithful Christian, working to shape a world of justice and beauty? Or again: Where is my brother or sister? Experiences of fraternal service such as the Missão País and many others that arise within academic communities ought to be considered essential for those attending university. An academic degree should not be seen merely as a licence to pursue personal wellbeing, but as a mandate to work for a more just and inclusive society, a truly progressive society. I am told that one of your great poets, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, was asked in an interview, which served as a kind of testament: “What would you like to see Portugal achieve in this new century?” She answered without hesitation: “I would like to see the attainment of social justice, the reduction of the gap between rich and poor” (Interview with Joaci Oliveira, in Cidade Nova, No. 3/2001). I put this same question to you, dear students, as “pilgrims of knowledge”: What do you want to achieve in Portugal and in the world? What changes, what transformations? And how can universities, especially the Catholic university, contribute to this?

Beatriz, Mahoor, Mariana and Tomás, I thank you for your testimonies. They all struck a hopeful note, full of enthusiasm and realism; you did not complain or escape into flights of idealism. You want to be protagonists, “protagonists of change”, as Mariana told us. As I listened to you, I thought of a phrase from the writer José de Almada Negreiros, which you may know: “I dreamt of a country where everyone was able to become a teacher” (A Invenção do Dia Claro). This old man now speaking to you — for I am an old man! — also dreams that yours will become a generation of teachers! Teachers of humanity. Teachers of compassion. Teachers of new opportunities for our planet and its inhabitants. Teachers of hope. And teachers who defend the life of our planet, which today is threatened with severe ecological damage.

As some of you pointed out, we must recognize the dramatic and urgent need to care for our common home. Yet this cannot be done without a real change of heart and of the anthropological approaches undergirding economic and political life. We cannot be satisfied with mere “palliative” measures or timid and ambiguous compromises, for “halfway measures simply delay the inevitable disaster” (Laudato Si’, 194). Do not forget this! Halfway measures simply delay the inevitable disaster. Rather, it is a matter of confronting head-on what sadly continues to be postponed: namely, the need to redefine what we mean by progress and development. In the name of progress, we have often regressed. Please study this carefully: in the name of progress, we have often regressed. Yours can be the generation that takes up this great challenge. You have the most advanced scientific and technological tools, but please, avoid falling into the trap of myopic and partial approaches. Keep in mind that we need an integral ecology, attentive to the sufferings both of the planet and the poor. We need to align the tragedy of desertification with that of refugees, the issue of increased migration with that of a declining birth rate, and to see the material dimension of life within the greater purview of the spiritual. Instead of polarized approaches, we need a unified vision, a vision capable of embracing the whole.

Thank you, Tomás, for reminding us that “an authentic integral ecology is not possible without God, that there can be no future in a world without God”. In response, I would say: make your faith credible through your decisions. For unless faith gives rise to convincing lifestyles, it will not be a “leaven” in the world. It is not enough for us Christians to be convinced; we must also be convincing. Our actions are called to reflect, joyfully and radically, the beauty of the Gospel. Furthermore, Christianity cannot be lived as a fortress surrounded by high walls, one that raises the ramparts against the world. That is why I was moved by Beatriz’s testimony. She said that it is precisely “within the field of culture” that she feels called to live the Beatitudes. In every age, one of the most important tasks for Christians is to recover the meaning of the incarnation. Without the incarnation, Christianity becomes an ideology — and currently there is the temptation towards “Christian ideologies”. Whereas the incarnation enables us to be amazed by the beauty of Christ revealed through every brother and sister, every man and woman.

In this regard, it is significant that to your new academic chair, dedicated to the “Economy of Francesco”, you have added the figure of Saint Clare. Indeed, the contribution of women is essential. In the collective unconscious, how often is it thought that women are second-best, only reservists, not appearing in the starting lineup? This happens in the collective unconscious. Yet, the female contribution is indispensable. In the Bible, we see how the economy of the family is entrusted largely to women. They are the real heads of the household, possessed of a wisdom aimed not merely at profit, but also at care, coexistence, and the physical and spiritual wellbeing of all, including the poor and the stranger. It is exciting to approach the study of economics from this standpoint, for the sake of restoring to the economy its proper dignity, lest it fall prey to unbridled market speculation.

The Global Compact on Education, with its seven overarching principles, encompasses many of these issues, from caring for our common home to the full participation of women and the need for innovative ways of understanding economics, politics, growth and progress. I encourage you to study the Global Compact and to become enthusiastic about its contents. One of the points it addresses is the need to educate about acceptance and inclusion. We cannot pretend that we have not heard the words of Jesus in Chapter 25 of Matthew’s Gospel: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (v. 35). I was moved as I listened to Mahoor’s testimony, when she described what it is like to live “constantly feeling the absence of hearth and home and of friends..., of being without a home, a university, or money..., tired, worn and beaten down by grief and loss”. She told us that she rediscovered hope because she met someone who believed in the transforming power of the culture of encounter. Every time someone offers a gesture of hospitality, it prompts a transformation.

Dear friends, I am very happy to see that you are a lively academic community, open to the current reality, where the Gospel is not mere decoration but an inspiration for your individual and collective efforts. I know that your lives are busy, between study, friends, community service, civil and political responsibilities, care for our common home, artistic activities, and so on. That is what it means to be a Catholic university: each part is related to the whole, while the whole is to be found in each of its parts. As you acquire knowledge and academic expertise, you will grow as a person, in self-knowledge and in the ability to discern the path of your future. Paths: yes. Mazes: no. So, carry on! A medieval tradition has it that when pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago met one another, they greeted each other by exclaiming, “Ultreia”, and responding, “et Suseia”. These expressions encourage us to persevere in seeking and in the risk of the journey, telling one another: “Come, take heart, keep going!” That is likewise my heartfelt wish for all of you. Thank you!

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti