In June of 1988, this transplanted Yankee has never heard the warnings against eating a raw oyster in a month without an “r” in its name. Yet, the moment I bite into that raw oyster, I know something is wrong. It does not taste right.

That evening, I bunk down at an Orlando Airport hotel. In the morning, I will be flying to Detroit to rent a car and drive to Holland, Michigan where an investment banking client is negotiating the financing of the expansion of the community hospital.

Before leaving my hotel the next morning, I phone my wife, Susan.

“You do not sound good.” She asks with a statement.

“Man, I’m coming down with something.” My answer is distracted and non-committal. “Just feels like a head cold, maybe. Nothing to worry about.”

After landing at Detroit Metro, I pick-up a rental car. My head is starting to pound as I leave Detroit for Holland, Michigan. Also, my throat is parched.

By the time I reach my hotel in Holland, it is clear to me that I am succumbing to summer flu. By the next morning, flu is off the table. I have trouble holding the phone steady.

“Susan, I have a high fever and I’m shaking.”

Shaking sounds less alarming than convulsions. But verbiage does not change the reality.

“They have arranged for someone to drive me to the airport nearest here.” With the energy of screaming, my voice barely manages to be just above a whisper. “I need for you to meet me at the Tallahassee Airport. I don’t think I can drive.”

Whatever this is, it is really bad. During the next four weeks, the fevers fall into a pattern, starting low and building to a very high level. Then, breaking for about twelve hours. Then, starting over. Dysentery is the order of the day. Nothing will stay in or down. And nothing seems to provide me any energy. Outpatient treatment accompanies an incredible number of tests and interrogations. Hepatitis. hiv . Parasites. Brucellosis.

The test results are all negative.

Meanwhile, the fevers keep getting higher, and I keep getting sicker.

“We know about one thousand things you don’t have.” My doctor feigns humour as he signs the order to admit me to the regional hospital. “We just don’t know what you do have.”

The obvious next sentence is left unsaid. I am dying.

The intravenous antibiotics do not even touch the progress of the disease. Finally, after my several days in the hospital that follow almost six weeks of extreme illness, the doctor shows up in my room outside of rounds.

“Please sit down.” He motions to Susan and slides a chair in her direction. She sits to my left and takes my hand in hers.

“And please listen carefully.” Now my doctor is speaking directly to me, as I lay in the bed with my head slightly elevated and a fever raging in the high 103s. “Are you able to hear me and understand me?”

I nod slightly, knowing that I will not want to hear him or understand his words. It is early evening, and I am extremely tired. Beyond tired. It has never occurred to me that a person could be this sick for six weeks and still be alive. I do not want to die. But, at this point, the thought brings a sense of relief.

“We cannot figure out what you have.” He speaks without gestures and without affect. My intuitive sense is that he is feeling failure.

“Clearly it is bacterial.” He pauses for a quick eye-check that Susan is securely seated. “Whatever it is, it has won and you have lost.

“Your liver has stopped functioning.” Another eye-check at Susan. “All the major organs in your body are engaged and they are shutting down.”

The room is completely silent. Too silent.

“Mr. Recinella ... Dale.” He clears his throat. “It’s over. You cannot survive the night. You cannot live more than another ten or twelve hours. You will not see tomorrow morning.”

Susan is absolutely rigid except for the squeezing of her hands wrapped around mine. I sense what he is going to say next. I never thought I would hear my doctor say those words to me.

“Mr. Recinella, you need to get your affairs in order.”

The children visit. Then, Susan’s mom takes them to our house. She is minding them at home while Susan waits for me to die.

Our pastor comes to administer the Last Rites. Before losing consciousness, I kiss Susan goodbye. She is crying. She is staying. She will be here through the end. She is on death watch before we have ever heard the term.

The fever spikes tremendously high. I cannot keep my eyes open. I want to but am unable to. My last visual moment is Susan, sitting next to my bed, looking at me as though the strength of her gaze could hold me here. It cannot. The fever has its way. My eyes fall closed. All is darkness.

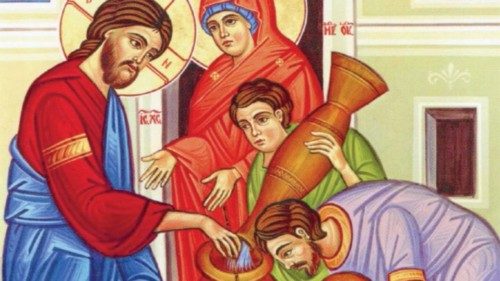

Suddenly, at some point in the middle of the night, I find myself standing in the center of a room. It is not my hospital room. It is dark except for the illumination pouring from the person in front of me. I recognize Him immediately. It is Jesus. He looks exactly like His picture that hung in my bedroom as a child. He glows with a heat that defies description, both warm and luminescent, radiating out, penetrating the whole room and even my body. He is gazing at me intently. But He is not smiling. He is deeply saddened. There are tears on His face. I realize that He is weeping softly.

“Dale.” His arms stretch out toward me as His head shakes gently with sorrow and disappointment. “What have you done with my gifts?”

The lawyer in me responds by defensive instinct. “What gifts?”

As Jesus obliges by listing my skillset, He does not look angry or perturbed. Just sad. Very, very sad. He details every aspect of my intellect, education, upbringing, personality, and temperament that is part of my worldly success.

But I still do not get it. The moment does not feel like a judgment. But every response that comes to my mind is defensive.

“I have worked hard. I have made sure that my children can go to the best schools.” Even as the words spill from my lips, it occurs to me that I am talking code for upper-class and expensive.

“We live in a safe neighbourhood; my family is safe.” There is that sensation again. While my mouth is yet moving, in my thoughts I hear, code for upper-class and exclusive.

“Our future is financially secure!” There it is again, the voice in my head, code for we have filled all our barns and are building bigger ones. Only this time the thought comes with a memory of Jesus’ words in Scripture about fools that fill their own barns (Luke 12:16-21).

“I have taken care of my family just like everybody else does.” The overt defensiveness of my voice makes me realize that I am arguing with somebody. Who? Jesus is not arguing back. Who am I arguing with? Myself?

Finally, His hands drop to His sides. His expression is not one of condemnation. Rather, it is like the look of dismay of a parent who has told their teenager something a thousand times and is beyond belief that the child has still not ever heard it. He speaks with a pleading that borders on exasperation.

“Dale, what about all my people who are suffering?”

In that moment, it is as if a seven-foot-high wave suddenly and unexpectedly breaks over me on an ocean beach. I am not at a beach and the wave is completely transparent, invisible but tangible. I can feel its substance. And it is acidic-corrosive in the extreme. It feels as if my very being will be dissolved in it.

Somehow, intuitively, I know in the moment that the acid is shame, the shame of the selfishness and narcissism of my life. I have used my family as an excuse for taking care of only me, my ego, and my false sense of importance. I struggle against the sense of dissolution penetrating my being.

“Please!” I summon the energy for my last plea as Jesus is still tearfully before me. “Please! I promise you. Give me another chance, and I will do it differently.”

That is it. That is all. The wave is gone. He is gone. The room is dark.

It is about 6:30 a.m. the following morning when I open my eyes. Susan has been sitting next to my bed all night waiting for me to die. I shudder at the reality of my last visual thought before the night, my mind’s last picture of her in this world.

“I’m not dead, am I?” My voice betrays its surprise at hearing itself again. There is a long moment before she responds.

“Well, you look pretty awful.” Susan smiles with the full irony of her very long night. “But obviously, you are not dead. You are still talking.”

There is another long moment of silence.

“Oh-oh.” My sigh bears the full weight of having no clue as to what I have promised Jesus I will do.

There is no more fever. The bacterium is gone. The doctor says it is impossible, truly impossible. Three years later the bacteria will be identified as vibrio vulnificus, a flesh-eating bacterium that causes deadly food poisoning and wound infections. It is overwhelmingly fatal even with external exposure. I swallowed it.

Nonetheless, the second half of my prayer has now been answered. I have seen myself, my choices and my life, as God sees them.

After Susan and I share with each other our experiences of that night, we look for an answer to the lingering question, “Now what?”

For me, the question seems to point in only one direction. Fix Dennis. Get Dennis down to Tallahassee and rescue him. That means making a list of actions to check-off. That is something I am good at.

I am still severely debilitated at the end of July. It is not easy to get on the plane to Baltimore-Washington International Airport. Or to catch the cab to the rehabilitation center where Dennis will be ready and waiting to return with me to his new home in Tallahassee. I have spoken with him on the phone several times, even last night before this trip. Everything is set.

When I arrive at the rehabilitation center, about a thirty-minute cab ride from bwi on this sunny Saturday morning, a staff member motions for me to stay in the cab. I have a sinking feeling in my gut as the staffer walks closer and motions for me to roll down my passenger window.

“He’s gone.” The staffer shrugs with an acquired sense of helplessness. “Dennis ran away about an hour ago. He appears to have snuck out through his window. We’ve looked everywhere, and no one can find him.”

“What do I do?” Without realizing it, my air of attorney-on-a-mission competence has evaporated, and I am mirroring his shrugs of helplessness. “What do I do? Everything is set. How can I help him if he is gone?”

“You can’t. Just go home. That’s all you can do.”

The return rides in the cab and the plane all blend together into a prolonged sense of confusion, mixed with anger, peppered with the physical pain of having made a trip far beyond my stamina.

“It’s a bad joke.” I mutter over-and-over to myself while rocking my cane from left to right. “This is all just a really bad joke.”

A few days later I am sitting in a follow up meeting at church with about thirty other men from the Scriptural renewal weekend in March. They have all heard the story of my night with Dennis in the streets of Baltimore. They have endured my illness and are as shocked as me that I am still alive. Now they are my community of grief as I struggle to comprehend what the heck God is doing.

Within the white stucco walls of our regular church meeting room, we sit in a circle of moulded plastic chairs, taking turns sharing the news that updates the stories of each of our lives since the big weekend. My anger and frustration are palpable. A couple of the men slide outward away from the orbits of my swinging cane to avoid direct impact from its punctuations as I speak.

“Why? What was the point of this whole stupid exercise?”

My questions hang in the air for a few minutes before a chuckle breaks out from one of the elders of our group. Jim Galbraith, a retired architect, a Scotsman who grew up on a ranch in the Dakotas during the Great Depression. He has that rare gift of being able to laugh so warmly that you know he is just as embarrassed as you are, but he is also as tickled as he knows you are going to be. What starts as a chuckle grows into a belly laugh. He cannot hold it back.

“Don’t you get it, Dale?” Jim is standing and has an arm around me, maybe to stop the orbits of my cane. “Don’t you see it?”

“Get what? See what?”

“Dale, maybe God did not bring you into Dennis’ life for you to save Dennis.” Jim is laughing so hard; he can barely speak. “Just maybe God brought Dennis into your life to save you.”

The room erupts. Everyone is laughing to the point of tears.

“I never thought of that possibility.” My lawyer self tries to salvage some dignity.

“We know!” Jim is doubling over while slapping both his knees. “That is what is so funny!”

For part 1 of “The story to my conversion”, see or English edition n. 21 — 26 May, 2023, p. 8.

By Dale S. Recinella

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti