The Bible

The lesson of the Other

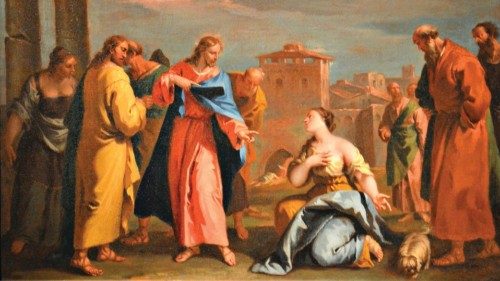

And from there he arose and went away to the region of Tyre and Sidon. And he entered a house, and would not have any one know it; yet he could not be hid. But immediately a woman, whose little daughter was possessed by an unclean spirit, heard of him, and came and fell down at his feet. Now the woman was a Greek, a Syrophoeni′cian by birth. And she begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. And he said to her, “Let the children first be fed, for it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs”. But she answered him, “Yes, Lord; yet even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs”. And he said to her, “For this saying you may go your way; the demon has left your daughter”. And she went home, and found the child lying in bed, and the demon gone. (Mk 7:24-30)

Christianity affirms that Jesus is indeed, the son of God, but made flesh. He too belongs to a culture, a world, a mentality and, paradoxically, some element of this context marks him.

Reading Mk 7:24-30 we come across the passage of the Syro-Phoenician woman, where Jesus’ encounter with this stranger is narrated. The request to heal her daughter is made in such a lacerating and excruciating manner that the apostles themselves seem to suggest to Jesus that they go to meet this desperate woman to get some respite themselves. And Jesus reveals the very cultural conditioning of the world in which he is immersed. “Let the children first be fed, for it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs”.

How can one fail to detect in these few words a statement typical of a self-contained Jew who is convinced that foreigners are rightly called “dogs”?

Jesus, therefore, radically belongs to the mentality of his people, but immediately afterwards, as his message is transformative, he also breaks his own cultural coordinates. In fact, later, having seen the faith of that woman, albeit a foreigner, he exclaims, “For this saying you may go your way; the demon has left your daughter” (Mk 7:29).

Paradoxically, the Syro-Phoenician woman, a foreigner, becomes an emblem, an example, a model precisely for the Jews: the categories that were proper to the time, and that Jesus himself had learned, are totally overturned. All the more reason why we should hope that this same conversion will also occur for us, that of putting others, even if foreigners, before us.

There are several interpretations of this episode in which Jesus crudely calls the pagans “dogs”. According to some, Jesus had this closed behaviour in order to educate his disciples to come out of a narrow mindset, and arrive at an open way of thinking, that is, to believe that God is also present in pagan peoples. From his environment and religiosity, he too was initially convinced that God and his salvation worked only within the confines of the Jewish people. What opened him to a different God was faith and the insistent message proposed by the Syro-Phoenician woman. Jesus as a man grew up and matured under the stimulus of people and, in this case, of a pagan woman. By some she is called Jesus’ teacher.

The value of differences

In the biblical way of seeing things, the living man is a man in relationship, a man capable of living with the other. Throughout the course of history, however, man has been tempted to take a shortcut that consists in conceiving the other as different, the stranger as the enemy, as a threat. Thus, the risk is to give oneself an identity “against” someone else; instead, different identities help one to recognise oneself. From this temptation also follows the imbalance, which is often noted, with regard to spaces to be shared, because too often they are seen, instead, as spaces to be defended. One must come to understand that cultural and religious differences are also a value.

A spiritual man, Cardinal Etchegaray, wrote about Christian denominations. “We must be happy to be different. Who among us can claim to exhaust the message of the gospel and reduce it to a single voice? Each must convert a little in the face of the other to correct what is too particular in his own vision [...] Otherwise our pilgrimage becomes a crusade, our testimony an ideology, our face a caricature. We are happy to be different!”

Cardinal Ratzinger himself, speaking about the Christian religion at a conference on ecumenism said, “Perhaps we are not yet all ripe for unity and we need the thorn in the flesh, which is the other in his otherness, to awaken us from a halved, reductive Christianity”.

by BATTISTA BORSATO

Presbyter and theologian of the diocese of Vicenza

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti