TheTestimony

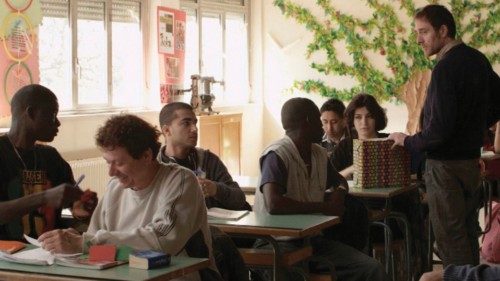

I teach Italian to foreigners in an evening school in Padua. The ongoing perception is that I am their first port of call and they are mine. Not immediately, not always. For example, in the first few weeks, the Nigerian girl called Cindy couldn’t look me in the face and constantly looked away. Sometimes she would put on her headphones and listen to her mobile phone, smiling at something that was not about the lesson at the time. One evening I handed back their corrected tests and Cindy had done well. I told her “You've done well”. Then she looked up and we recognised each other. Most of the students have only been in Italy for a handful of months, or two or three years, but they have never attended an Italian school or come into contact with a local person like they are doing now with me. Therefore, we look at each other as if we had arrived together at the top of a hill, each coming from a different direction, finally reunited in a common space. This is an encounter that surprises me lesson after lesson. Asian students discover that Westerners devote a considerably large amount of time to the gym, to dogs, and to evenings at the bar with friends. The Western students hear with amazement how an Asian’s day includes nothing but work, family and prayer.

In this common space, from the very first moment, God is always present. I speak of the fact that my “participants”, as foreigners who take an Italian course are called, are almost all Muslims. They were born and raised in India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, and Somalia. The women wear the burka if Bengali, only the hijab if Indian, or they wear their hair long and free if Maghrebi. Our talks about God and prayer occur very frequently, as the experience of faith is in concrete, everyday things in a way that to Europeans sounds somewhat anomalous, and very new.

In this dimension of commonality, I can see myself through their eyes. I wear jeans, I drive to school, I am not married and have no children. A woman without a family, why? What could have happened? Yet, the greatest surprise came when I answered a new question, crucial for them. Do I not pray to my God? What had happened that was so serious? One evening, with a small group and after the topics of the teaching unit had concluded, we stood in a circle and chatted. It is on the syllabus for the students that the traditions of Christmas and Easter, including customs that are not directly related to religion but to ancient, pagan roots such as the decorated tree, the Easter eggs, the lights adorning the cities are explained about. You see, I indicated on the digital board, this is Palestine. It is a new place for many of them, born in or near India. “Here Jesus was born in a manger, next to two animals that warmed his cradle filled with straw”. They listen with great interest. Then, I say, Jesus started preaching. He told stories to facilitate understanding, they are called parables. “Tell us one”, Kazhi, the Bengali boy, asks me. So I tell the parable of the adulteress who was about to be stoned to death, which is one of my favorites. “You, what would you have done?” I ask my small audience of students. My Indian student has an enigmatic smile on her face. She is debating. The woman has done wrong, committed an unforgivable act. “Jesus,” I say, “says that it is easy to pray for our friends. And that it is necessary to pray for our enemies”. “But you don't pray,” the Pakistani boy reminds me. Khalid is only nineteen, he has spent six of them walking from Pakistan to Italy. He has managed to keep his habits and his faith like a precious stone kept in his pocket.

The Nigerian student called Cindy is Pentecostal and intervened, “God looks at the hearts of men and women, sees if it is good. That is what counts”. The Lebanese boy is silent because he confided in me one day that he does not pray or observe Ramadan; yet, he believes there is God. For him too, it is important to discuss these questions, so he says, “When I see a forest, a river, the starry sky, it is impossible for me to imagine that there is not a God who created all this”. He has become friends with the Somali student, who in a few years has wandered all over Europe in search of a sheltered place. He has three children who live in Sweden and whom he cannot see because they have discovered that he has given his fingerprints in Italy and therefore according to the law must seek asylum in this country that he barely knows.

The Somali boy, Hassan, does not understand the use of wine in the liturgy. As Easter approaches, I tell them about the Last Supper and in the meantime, I look for an image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. “Jesus, despite knowing what is about to happen, takes the bread - do you see it on the table?” “Jesus becomes the bread that is eaten by the faithful? “. They look at me in amazement. The boy from Lebanon has studied literature and teaches Arabic, “As for poems, we understand them at a more intimate and wiser mind level”.

The conversations with my students are some of the most profound I have ever had. I conclude by talking about the last days of Jesus’ life and the crucifixion. I show an image of Golgotha: “This is why Christians make the sign of the cross and say Amen”. Amen? They are amazed. Amen is the word they say at the end of the prayer, “Amin”. During the course we often find words that are used and have flourished in very distant places that sound very similar, for example, the Italian “babbo” and “abbu”, in Hindi. We discover unthinkable etymologies, for example “sciroppo” and “ciabatta” in Arabic sound almost identical to Italian. In Somalia, several Italian words such as for skirt and car have remained in the local language. After all, ours is a weaving of threads of commonality. The thread they favour is that of faith, but there are many other threads, for example, words, food, and kindness. Often all our threads intersect.

One day I thought that my Italian class was made up of the people I would like to take as an example to my alternative religion students in the vocational institute where I teach the rest of my hours. The children in this class of mine are sixteen years old and come from non-believing families or foreign Muslim or Protestant families. They are restless, often apathetic. Like so many of their peers to whom I teach English, they possess a variety of talents but cannot even name them or, if they have already identified them, they seem convinced that they will be of use to almost no one. They lack the sense of familiarity and community that I find in my Italian course. They are bewildered, especially the Italians. They look an awful lot like the main character in the film I showed them - Good Will Hunting, where a boy lives a dull and violent life until he discovers he is a mathematical genius. Yet at the end what matters most to him is not his university career but finding a way to stay close to the girl he is in love with. My students loved the film very much.

In the last days of March, Ramadan began. Since my course starts at eight o’clock in the evening, my Muslim students in the Italian course were afraid of arriving late because after a whole day of fasting they had to eat and then pray. Kazhi, the Bengali boy who got a job in a Venetian restaurant, arrives half an hour early with food in a small bag and politely waits for the school staff to open the room where the students can finally do their ‘iftar’, the breaking of the fast. First, they drink water and eat dates. They open their trays with fragrant food. The women of the family, often Bengali or Moroccan, bring over plenty of food to give to classmates who could not cook because they were at work in the afternoon. Everything happens in a peaceful silence while from the window the gaze meets first Saint Antonino, the church in the northern quarter of Padua that houses the cell where St Anthony died on June 13, 1231, followed by the sunset colored sky.

The Indian girl called Shaila arrives now when it is dark. “The child,” she always says. She means that she had to wait for her husband to return from school so as not to leave her daughter alone. She almost always brings a container with food for me. She tells me that she is also studying for her driving licence. And then she would like to take the eighth grade. Six months into the course we know a lot about each other. We celebrate the life that happens. The Polish boy offered chocolates when he took out a mortgage while the Pakistani boy announced that he would be absent for surgery. “I am afraid,” he said. So the Bengali women prepared sweet milk balls for him as consolation.

by LAURA EDUATI

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti