Gospels

Until the pandemic, I had been teaching almost every semester at Riverbend Maximum Security Institute, a men’s prison in Nashville, Tennessee, USA, where the state’s death row is located (Tennessee is among the many US states that practice capital punishment). I would bring twelve “free-world” students from Vanderbilt University Divinity School to the prison, where we would hold class with twelve “insider” students. Here are three of the countless profound comments my insider students made in studying the Gospels. I have permission from these men to share their thoughts, and to do so without naming them. They do not want seeing their names in print to cause pain to the families of their victims. Yet, as we will see, their namelessness also touches upon the Gospel texts.

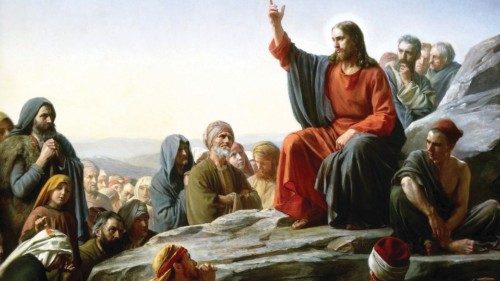

First, in reading the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7), we came to the text traditionally known as the “Lord’s Prayer,” the “Our Father,” or in Latin, the Pater Noster. The prayer also appears in the Gospel of Luke. In each case, the wording differs. The Greek of Matthew 6:12 reads, “And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” The Greek of Luke 11:4 reads, “And forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone indebted to us.” Luke makes clear that “debt” is another word for “sin.”

Jews at the time of Jesus used several metaphors to describe sin: sin could be a weight or a burden that needed to be lifted, a stain that needed to be cleansed, or a debt that needed to be paid. The term “hovah” in Aramaic, the language Jesus spoke, could mean both “debt” and “sin”; the context helped Aramaic speaker and readers determine which connotation was intended. But in Greek, the language of the Gospels, the word for “debt” meant a monetary debt; it did not have the connotation of “sin.” What did Jesus then intend when he taught this prayer, in Aramaic, about forgiveness: was he speaking of money, of a debt that one person owed to another, or was he speaking more broadly about sin?

My first thought in investigating this prayer was that Jesus intended “forgive us our debts,” as Matthew 6:12 suggests. I thought he was calling for economic justice, for the Jubilee year when all debts are forgiven. As Habakkuk 2:6 laments, “Alas for you who heap up what is not your own! How long will you load yourselves with goods taken in pledge?” Then, I thought, Luke wanted to make clear to readers that the prayer concerned not money, not economic debt, but sin, the sin of failing to manifest love and compassion.

At Riverbend, when we got to this prayer, I suggested that Luke changed a focus on money to a focus on sin. I also suggested it was easier to forgive a sin than a debt. “If you sin against me,” I said to the class, “I can forgive you, but if you owe me $100,000 and I have major expenses to meet, I want the money.” One of my insider students – a quiet man who had been sentenced to multiple life terms for murder – then spoke. “Lady,” he said to me, “you do not know what you are talking about.”

He then described how, in a program known as victim-offender mediation, he met regularly with the family members of the people he killed in a drug deal that went horribly wrong. The family began this process with hate for my student, and my student began the process with both shame and guilt. However, the more they met, the more their feelings changed. Finally, the family members said to him, “We forgive you.”

“Lady,” he said to me, “You do not understand sin, and so you do not understand forgiveness. The forgiveness they offered me was worth infinitely more than any economic debt.”

What might Jesus have taught? I think he was telling rich people who were among his disciples that they should “give to everyone who begs from you, and do not refuse anyone who wants to borrow from you” (Matthew 5:42). More, he was telling all his disciples that just as God has the mercy to forgive them, so they should have the mercy to forgive others.

Yet, as my “free world” student Maria Mayo noted, sometimes we do not have the capacity to forgive. For some of us, the hurt, is too deep, and too raw, to grant forgiveness, especially when those who hurt us do not repent. In such cases, Maria turns to Luke 23:34, where Jesus prays, “Father forgive them….” He could have pronounced the forgiveness himself, but suffering the torture of crucifixion, he leaves the forgives to God the Father. My insider students said they found this reading of comfort.

Second, as we continued in Matthew’s Gospel, we came to 12:31, where Jesus tells his followers, “People will be forgiven for every sin and blasphemy, but blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven.” The discussion turned to what would constitute such a blasphemy. One of my insider students, a defrocked Roman Catholic priest in prison for child molestation, with tears in his eyes, said, “blasphemy against the Spirit is thinking that God would not love someone like me. Blasphemy is denying the infinite love of God.” No matter how horrible the crime, the love of God prevails.

Third, when we came to the death of Jesus, we talked about the centurion who proclaimed Jesus the Son of God, about the faithful women who had followed him from Galilee to the cross, and about Joseph of Arimathea, who had the courage to go to Pontius Pilate, ask for the body of a condemned man, and then place that body in his own tomb. One of my insider students asked, “Who stayed with the other two men crucified with Jesus that day? Who took their bodies down from the crosses and provided them a proper burial? Who mourned for them?”

The questions from the insider students continued: “Who will be with us when we die? Who will claim our bodies? Who will mourn us?” The insider students found comfort in the infinite love of God. At the same time, they issued challenge to me and to my divinity students who were studying to become ministers and religious educators: “Will you remember us? Will you tell your congregations to remember us?”

My insider students are guilty of murder, rape, torture, and child abuse. They are also my friends. I do not think of them as “that murderer” or “that rapist.” I think of them by their names, and I know them by what they say in class and what they write in their papers. At the same time, I think about their victims. It is not my role to forgive them for what they did because forgiveness is the prerogative of their victims, and of God’s; nor is it my role to damn them, for they too are in the image and likeness of God.

Heaven forbid that they, or we, are known by the worst thing we have ever done. Moreover, heaven forbid that we would put limitations on the love of God.

By Amy-Jill Levine

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti