As the Cardinal Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Jorge Mario Bergoglio had a very deep relationship with the Jews of his city. He cultivated open dialogues with rabbis, community leaders, and individuals and developed many friendships that deepened significantly over time.

I am among those who were blessed by enjoying such a friendship with him, one based on our regular interreligious conversations. Together we wrote a book of our dialogues (On Heaven and Earth) and recorded thirty-one programs for the archdiocesan television channel. He spoke at several different local synagogues, including my own, where he gave warm and spiritually inspiring messages to their congregations. He was a constant source of assurance and support, especially after the horrible bombing of the Buenos Aires Jewish community center in 1994. Especially touching to me personally was his request that I compose the preface to his authorized biography. All these things testified to Cardinal Bergoglio’s sincere dedication to building relationships and friendships with Jews and their community institutions.

After the unprecedented resignation of Pope Benedict xvi , and my friend’s historic election as the first pope from Latin America, everyone who read about this cardinal from “the end of the world” (as he put it), learned how important to him were his experiences with the Jewish people.

After becoming Pope Francis in 2013, he maintained contact with his Jewish friends through emails and telephone calls. To me and to others, he continues to express his personal affection, inquiring after our health and about the doings of our families. Has this ever happened before in the history of relations between Catholics and Jews?

Less than a year after his papal election, he issued the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium. It was a wide-ranging overview of the state of the Catholic Church and of the world as he began his pontificate. Its section on interreligious relations authoritatively summed up developments since the 1965 Second Vatican Council declaration Nostra Aetate. Urging, as he always does, that dialogue among peoples and religious traditions must be a priority, he expressed important insights about the Church’s relations with the Jewish people.

These include the memorable sentences that “Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples” and that “God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word.” This explains why dialogue between Catholics and Jews is so important to Pope Francis: we can encounter together God’s wisdom in our sacred texts in ways that are not paralleled in conversations between any other religious traditions.

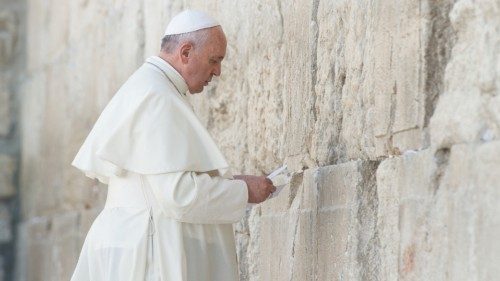

In 2014, Pope Francis undertook a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and prayed at the Western Wall. In 2016, at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, he could find no fitting words to express his horror at that place, asking God before the journey to give him the grace to weep. I was privileged to witness both of these memorable visits.

While in Jerusalem, Pope Francis was the first pontiff to place a bouquet of flowers on the tomb of Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, thereby honoring the movement that recreated Jewish culture in its ancient homeland. Ever vigilant about human rights, he had the previous day also placed his hands on the wall that divides Israel from Palestine. I see this as more than a mere political act. It was a prayer asking God to bless Israelis and Palestinians with peace, to remove all walls of separation and hatred and replace them with relationships of dialogue and mutual understanding. His response to a young Palestinian from the Dheisheh refugee camp, who expressed the frustration of his people, received a far-sighted response from the Pope: We cannot live chained to the vicious shackles of the past, we must change our frames of reference and find the path that allows everyone to develop together with dignity. The meeting for peace shortly afterwards in the Vatican gardens was an attempt in miniature to express this. It iconically brought together Presidents Peres and Abbas, with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, to plant a symbolic olive tree of peace, that, with God’s help, will bear fruit in the future.

Very importantly, as long as I have known him, Pope Francis has vigorously condemned all verbal and physical attacks upon Jews simply because they are Jews. This constant message is especially comforting for Jews around the world in the present time of multiplying antisemitic appeals and murderous violence.

Relatedly, the opening in 2020 of the Vatican archives during the pontificate of Pope Pius xii was another act of great significance by Pope Francis. “You have to know the truth” is a principle that he has repeated on multiple occasions. He is well aware that without such a commitment to truth, no relationship can deepen beyond superficialities.

However, perhaps the most important feature of Pope Francis’ interactions with the Jewish community is the unquestionably sincere affection for Jews that he constantly demonstrates. It seems to me that most Jews feel the same way about him. May that mutual fondness be the model of Catholic and Jewish interactions for all generations to come!

* Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Rabbi Abraham Skorka *

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti