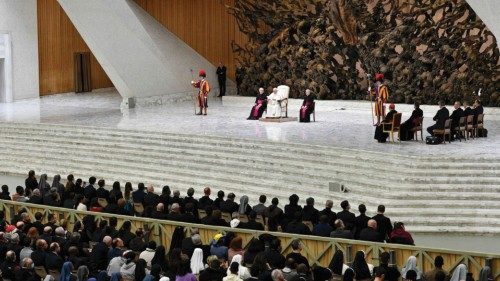

On Saturday morning, 25 February, Pope Francis received in audience rectors, lecturers, students and staff of the Pontifical Universities and Institutions in Rome. Recalling Saint Ignatius of Antioch, he highlighted the importance of harmony between the mind, the heart and the hands. The following is the English text of the Holy Father’s words which he delivered in Italian in the Paul vi Hall.

Your Eminence,

Distinguished Rectors and Professors,

Dear brothers and sisters, good morning and welcome!

I thank Professor Navarro for his words and all of you for your presence. As the Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium reminds us (cf. Prologue, 1), you belong to an extensive and multidisciplinary system of ecclesiastical studies, which has flourished throughout the centuries thanks to the wisdom of the People of God scattered throughout the world, yet one that is closely linked to the evangelical mission of the whole Church. You are part of a richness that has grown, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, through research, dialogue, discernment of the signs of the times and listening to many different cultural expressions. In this you stand out for your special — even geographical — closeness to the Successor of Peter and his ministry of joyfully proclaiming Christ’s truth.

You are women and men dedicated to study, some for a few years, others for a lifetime, with various backgrounds and skills. First of all, therefore, I would like to say, in the words of the holy Bishop and martyr Ignatius of Antioch: learn to “sing as a choir”.1 To sing as a choir! Indeed, the university is a school of harmony and consonance among different voices and instruments. It is not a school of uniformity: no, it is one of harmony and consonance among different voices and instruments. Saint John Henry Newman describes the university as the place where different forms of knowledge and perspectives are expressed in symphony; they complement, correct, and counterbalance each other.2

This harmony must first of all be cultivated in yourselves, in the three kinds of intelligence that resonate in the human soul: that of the mind, the heart and the hands. Each of these has its own timbre and character, and all of them are necessary. The language of the mind should be united with that of the heart and that of the hands: there should be a unity in what you think, feel, and do.

In particular, I would like to dwell with you for a moment on the last of these three: the intelligence of the hands. It is the most sensory, but by no means the least important. In fact, it can be said to be like the spark of thought and knowledge and also, in some ways, their most mature outcome. The first time I went out to Saint Peter’s Square as Pope, I approached a group of young blind people. And one of them said to me, “Can I see you? Can I look at you?” I didn’t understand. “Yes” I told him. And with his hands he looked — he saw me by touching me with his hands. This really struck me and helped me understand the intelligence of the hands. Aristotle, for example, said that our hands are “like the soul,” because of their power of sensation, with which they distinguish and explore.3 And Kant did not hesitate to describe them as our “external brain”.4

The Italian language, like other neo-Latin languages, highlights the same concept, using the verb prendere [to take], that typically indicates a manual action, as the root of words such as comprendere [to understand], apprendere [to learn], and sorprendere [to surprise], which indicate, instead, acts of the mind. While the hands take, the mind understands, learns and is surprised. Yet for this to happen, our hands must first be sensitive. The mind will not be able to comprehend anything if the hands are closed by greed; or if they let time, health and talents slip through their fingers; or if they refuse to give peace, to greet or to take another by the hand. We cannot understand others if our hands have fingers pointing mercilessly at the errors of our brothers and sisters. And we cannot be surprised by anything if our hands do not know how to be joined and raised to heaven in prayer.

Let us look at the hands of Christ. With them He takes bread and, having blessed it, breaks it and gives it to the disciples, saying, “This is my body”. Then He takes the cup and, after giving thanks, offers it to them, saying, “This is my blood” (cf. Mk 14:23-24). What do we see here? We see hands that, as they take, give thanks. Jesus’ hands touch the bread and wine, the body and blood, life itself, and they give thanks. They take and give thanks because they feel that everything is a gift from the Father. It is not coincidental that the Evangelists, to indicate this action, use the verb lambano, which means both “to take” and “to receive”. Like Christ, let us have “Eucharistic” hands, accompanying every contact and touch with humble, joyful and sincere gratitude, therefore creating harmony within ourselves.

In preserving this inner harmony, I invite you to “sing as a choir” within the diversity of your communities and among your various institutions. Over the centuries, the generosity and foresight of many religious orders, inspired by their charisms, has enriched Rome with a remarkable number of Faculties and Universities. Nowadays, however, faced with a smaller number of students and teachers, we risk dissipating our valuable energies due to the very multiplicity of centres of study. In this way, instead of fostering the evangelical joy of study, teaching and research, we face the threat of being hampered by fatigue. We should pay attention to this. Especially after the Covid-19 pandemic, we urgently need to initiate a process that leads to effective, stable and organic synergy among academic institutions, in order to better honour the specific purposes of each and to further the universal mission of the Church.5 And we must not argue among ourselves over taking on an extra student or an extra hour of study. I invite you, therefore, not to settle for short-term solutions and not to think of this process of growth simply as a “defensive” action, aimed at coping with dwindling economic and human resources. Instead, it should be seen as an impetus toward the future, as an invitation to welcome the challenges of a new era in history. Yours is a very rich heritage that can foster new life, but it can also inhibit it if it becomes too self-referential, if it becomes merely a museum piece. If we want this heritage to have a fruitful future, its custody cannot be limited to maintaining what has been received. Instead, we must be open to courageous and, if necessary, even new developments. It is like a seed that, unless it is scattered in the soil of concrete reality, remains alone and does not bear fruit (cf. Jn 12:24). I encourage you, then, to begin a confident process in this direction as soon as possible, with intelligence, prudence and boldness, always keeping in mind that reality is more important than the idea (cf. Evangelii Gaudium, 222-225). The Dicastery for Culture and Education, with my mandate, will accompany you on this journey.

Dear brothers and sisters, hope is a choral reality! Look behind me, at the sculpture of the Risen Christ, the work of the artist Pericle Fazzini, commissioned by Saint Paul vi to have a prominent place over this stage and this hall. Observe Christ’s hands: they are like those of a choirmaster. The right one is open: it directs the choir as a whole and, reaching upward, seems to ask for a crescendo. Yet the left hand, while facing the whole choir, has its index finger pointed, as if summoning a soloist, saying, “It is your turn!” Christ’s hands involve both the choir and the soloist, for in a concert, the role of one harmonizes with that of the other in a constructive complementarity. Please: never be soloists without the choir. For “It is everyone’s turn all together” and at the same time, “It is your turn!” This is what the hands of the Risen One say: it is up to all of you and to each of you! As we contemplate his gestures, let us then renew our commitment to “sing as a choir”, in harmony and in the consonance of voices, docile to the living action of the Spirit. This is what I ask in prayer for each one of you and for all. I bless you from my heart, and please do not forget to pray for me.

1 Cf. Letter to the Ephesians, 2-5.

2 Cf. The Idea of a University, Rome 2005, 101.

3 Cf. The Soul, III, 8.

4 Pragmatic Anthropology, Rome-Bari 2009, 38.

5 Cf. Address to Participants in the Plenary of the Congregation for Catholic Education, 9 February 2017.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti