“We need constantly to be reminded, and I hope this trip reminds people that the normal is for the Church to work as one”.

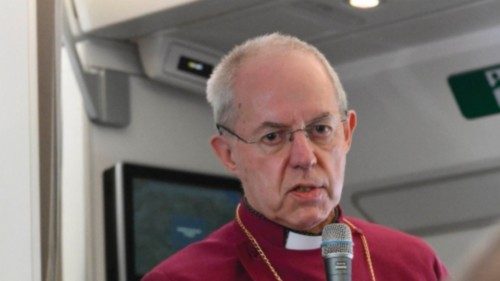

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, shared that consideration with Vatican News while still aboard the return flight to Rome from Juba. Following a joint press conference, Archbishop Welby granted the following interview about the ecumenical pilgrimage of peace which he carried out with Pope Francis and the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, Rt. Rev. Iain Greenshields.

Archbishop Welby, what are your impressions at the end of this visit to South Sudan, a pilgrimage made together with the Pope and the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, to foster peace and reconciliation in a country battered by civil war and poverty?

I think the trip comes with an effect at the local [level] South Sudan, which I’ll come back to, and an effect at the global. The fact that these three religious leaders have gone together for the first time ever, certainly since the Reformation, before which two of our Churches did not exist, is a sign of hope for peace and reconciliation around the world.

If those who spent 150 years killing each other and the next 300 condemning each other can now find themselves seeking peace and reconciliation together, then anyone can.

I don’t normally wear it, but at the moment I’m wearing the ring that Pope Paul vi gave to Michael Ramsey in the 1960s as the first sign of the link between our Churches. And that link — that ring — and then the pastoral staff that the Pope gave me in 2016, those together speak powerfully of a change of heart.

That brings me to South Sudan. We need a change of heart. The move of the Spirit in the Churches, especially many moves within the Charismatic movement, I would suggest, and moves among congregations at a local level, have broken down many of the barriers between us and have enabled us to live ecumenism, so you have ecumenism acted out.

The Second World War and since and the Iron Curtain and Communism gave us the ecumenism of suffering. And ecumenism of carrying the gospel of peace, both for physical peace in war and peace in the human heart, is the third thing.

And in South Sudan, my cry and prayer is for the human hearts of the leadership to be changed. When I was speaking out there the last couple of days, you could hear the shouts from the crowd when any of us mentioned peace, the security of women, and the need for an end to corruption. The people of South Sudan are calling for peace. The leaders must give it.

This common pilgrimage is a great sign for the world, also for ecumenism, as you said. Can it have significance for the future, for other countries and other situations? Is it perhaps a new way for Christians to work together for peace and reconciliation, even if they are divided into different Churches and confessions?

If this was a dialogue, I’d put back to you the question: ‘How many people rose from the dead on Easter Sunday?’ One. So how can we be many Churches? So, what do we do about that? There is one Resurrection, which is the source of our life. There is one crucified God, which is the source of our forgiveness. There is one Spirit, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians, which is the source of the life of the Church and our giftedness.

God has done everything that makes it possible for us to reconcile. It is only human pride that resists it. There is also an extent to which it’s not a conscious pride, but it’s like couples in marriage counseling that I’ve met who’ve really lived several separate lives for many years. And they’ve got used to being apart. They consider it’s normal.

We need constantly to be reminded, and I hope this trip reminds people that the normal is for the Church to work as one. The abnormal is for us to compete. I don’t know how deep ecumenism has gone. It is very wide, but I’m not sure that it’s deep enough within the hearts of many Christian leaders around the world.

We all need the confrontation with Christ who calls us and says, ’Follow me’, not follow me and him and him and him, and so on.

By Andrea Tornielli

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti