Women who go beyond. This is how missionaries can be defined, here paraphrasing Madeleine Delbrêl’s definition. These people are those who set out towards distant horizons and remote places where they live in the sense of being witnesses and often die as martyrs. In addition, these are the women who “without a boat”, cross cultural, social and spiritual frontiers to reach the other. As Pope Francis reminds us in his message for the most recent World Missionary Day, “Christ’s Church will continue to ‘go forth’ towards new geographical, social and existential horizons, towards ‘borderline’ places and human situations, in order to bear witness to Christ and his love to men and women of every people, culture and social status. In this sense, the mission will always be a missio ad gentes, as the Second Vatican Council taught. The Church must constantly keep pressing forward, beyond her own confines, in order to testify to all the love of Christ”.

It is impossible to draw a precise identikit of a missionary because the word “mission” encompasses pluralistic, multidimensional, and polychromatic factors. Until the second half of the twentieth century, the term mission was used to refer to special Church activities, which was a definition given to it by Jesuits in the sixteenth century. In the boom era of missionary activity in the 19th century, it referred to the somewhat romantic figure of the presbyter who had been officially sent out by the ecclesiastical hierarchy to a non-Christian country with the mandate to convert the population and build up an ecclesial community. Paradoxically, this formula excluded women. Yet, this very period saw the blossoming of extraordinary female figures, for example, the very important missionary nuns, from Francesca Saverio Cabrini, an apostle to migrants, and Laura Montoya, a pioneer in the defence of the Amazonian natives. These and other women went beyond in many ways, including the overcoming of prejudices pitted against them.

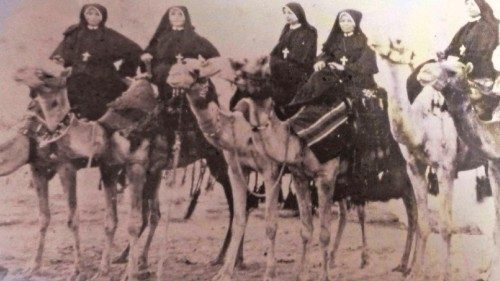

It was January 1, 1872 when three girls, Maria Caspio, Luigia Zago and Isabella Zadrich, founded the original nucleus of what would later become the first exclusively women’s missionary institute to be established in Italy, called the Pious Mothers of Nigrizia. Today, they are known as the Combonians. The founder, called Daniele Comboni, was aware of the audacity of the choice and the perplexity it risked arousing. What made him persevere was the profound conviction of the need for women, who are the witnesses of God’s compassion for the poor. For this reason, he compared “his” nuns to “a priest and more than a priest”. They are, he wrote, “a true image of the ancient women of the Gospel, who, with the same ease with which they teach the ABC to abandoned orphans in Europe, face months of long journeys in 60 degree heat, crossing deserts on camels, and riding horses, sleeping in the open air, under a tree or in a corner of an Arab boat; they help the sick and demand justice from the Pashas for the unhappy and oppressed. They do not fear the lion’s roar; they deal with all labor, disastrous journeys and death, to win souls for the Church”.

Other institutes were established in the years that followed, for example, the Xaverian Sisters, the Consolata Sisters, and the Missionaries of the Immaculate.

What undermines the “classical” concept of mission and a missionary is its association with the West’s colonial expansion. There is a certain narrative that tries to integrate the transmission of the faith into the “civilizing work of the white man” against “primitive or savage” peoples. It was the Second Vatican Council that cleared away any ambiguity and gave unprecedented depth to the missionary impulse. Mission is not one of the many ecclesial offices but a constitutive dimension of the Church that participates in the missio Dei. From this perspective, mission was configured as a dynamism the aim of which was to reach out to the whole world to transform it into the People of God. The latter is missionary because God is missionary. In today's ecclesiology, the Church is considered essentially missionary, meaning it exists while it is sent and while it is constituted in view of its mission. This turning point is described well in an article by historian Raffaella Perin [p.12]. Evangelii Gaudium, inspired by the Aparecida document and the stimuli of the Synod on New Evangelisation, takes up this perspective rigorously. In the “outgoing Church” of which Pope Francis speaks, the style, activities, schedule, language and structure are transformed by the missionary choice, which combined constitutes its pivot. The reform of the Roman Curia, contained in the Apostolic Constitution Praedicate Evangelium, is the concrete embodiment of this, as illustrated by canonist Donata Horak [p.18].

Being a missionary is, therefore, a way of being a member of an ecclesial community. It is not sociology. Mission is not an NGO, as the Pontiff has repeatedly stated. That is, it is not an institutionalized activity, as a function to be performed, or a commitment to be carried out, albeit for charitable and benevolent purposes. Instead, it is the nature of the Church; the engine of her action. Missionary concerns the heart of the Gospel; concern for the excluded and passion for the Kingdom. As Agostino Rigon, Director General of the Mission Festival states, “If God is concerned about the world within, the field of missio Dei is also the whole world; every human being and all aspects of their existence”.

It is fraternity that drives a man or woman to become the neighbour of the fallen on a street corner, wherever they may be. Be they indigenous people expelled from their lands, trafficked victims, child slaves, the Roma trapped on the outskirts of cities, or migrants condemned to an invisible pilgrimage. To help them get back up and accept to be lifted up by them. This is because the discarded are teachers of life and faith, as highlighted by an unprecedented project of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, which has created a sort of “chair of the poor in theology”. A group of experts addressed the great questions of theology to a group of marginal people among the marginalised. The answers are a distillation of the Gospel.

From this, however, a crucial question arises. If all the baptized women and men are necessarily missionaries, does the choice of those - lay and religious - who leave their own country and go to distant places to proclaim the Gospel with their lives and works still make sense? “Of course I am convinced it does”, says Marta Pettenazzo, a religious of the Missionaries of Our Lady of the Apostles and the first woman to lead the Conference of Italian Missionary Institutes (CIMI) between 2014 and 2019. “The missionary commitment concerns each and every one. Some, however, have been called to dedicate their entire existence and talents to the witness of the Gospel, within and beyond their own Country”. A mission, therefore, understood at three hundred and sixty degrees and addressed to human frailty wherever it is found. While the geographical horizon is no longer dominant, it has not disappeared. “The so-called missio ad extra, that is, experienced in other nations than one's own, is one of the dimensions of the mission and continues to be the priority for some Institutes or Congregations. At the heart of this choice is not so much the physical displacement as the existential behaviour that implies the readiness to leave. This translates as leaving what we know to go towards something else. Moreover, when we do that, we necessarily put ourselves in a position to learn. The mission has taught me that we only give in the way we learn”, emphasizes Sr. Marta.

Once again, the dimension of “going beyond” emerges in which the contribution of women becomes fundamental. This has always been so. The first missionary in the history of Christianity was Magdalene, as biblical scholar Marinella Perroni tells us [see p.16]. However, contemporary mission, at the heart of which lies the caring for and the accompanying of, has a very feminine face, as shown by the kaleidoscope of stories collected in this issue. From that of Lisa Clark, a missionary of non-violence in civil society and within institutions, to the story of Sister Zvonka Mikec from the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians Institute, who has been a life-long missionary in Africa, who met writer Tea Ranno, a former Salesian student, in Rome.

The recovery of the feminine, long associated with irrationality and inability to manage, as the Protestant theologian David Bosch argues, is fundamental to freeing the concept of mission from any claim to dominance, from any performative anxiety, from any efficientism paradigm. Only a missionary who combines vigor with tenderness knows how to create spaces of authentic gratuitousness.

Certainly, such a mental and spiritual stance requires a path of integral formation, which remains one of the open challenges. Institutes and congregations, for the nuns and or laywomen who belong to them, increasingly combine basic theology with advanced studies in missionology, as well as a specific curriculum for the work they do in the various works, from health to education. “Of course, the part on interculturality should be strengthened more”, says Sr. Marta. For those, on the other hand, who choose to leave with associations or through the diocese, in addition to internal training, there are specific courses, including that of the Centro Unitario per la Formazione Missionaria (CUM) [Unitary Centre for Missionary Training] in Verona.

The sore point, especially in times of global recession, remains sustenance. Solidarity and works are the first sources even if they are perennially insufficient. Often the contribution of benefactors covers the implementation of specific projects. It is more difficult, however, to find funds for their upkeep, which is indispensable for the missionaries to be able to dedicate themselves full-time to the poor. The Religious and laywomen often opt to be introduced to the host countries’ dioceses. However, a question to be resolved remains, which is the how to render their contribution recognizable and their commitment to pastoral work fully adequate in relation to the work they do and suitable for sustaining themselves. An ongoing pioneering approach is that of inter-congregational and, at times, mixed missionary communities, which allow relationships of reciprocity between genders to be fully experienced.

In short, mission in the 21st century cannot do without women. “Their creativity is indispensable for dealing with the borderline situations in which we are immersed in mission. For me, a missionary woman is the one that helps to give birth to the faith both in those who do not know it and in those who have lost the sense of it”. A “midwife of the Gospel” who is not anxious to baptize or, worse, to win proselytes, but seeks to open windows to let the breath of the Spirit enter the women and men of this time.

by Lucia Capuzzi

Journalist for the Italian national newspaper, Avvenire

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti