One of the first things we learn when we begin to study the Old Testament is that one of the biblical names for God is Go’el. This is a term that in the earliest tribal law indicated the closest relative whose task it was to avenge the offences received from some family member. Later it was spiritualized and attributed to God himself, who was expected to be the avenger, and the redeemer of his chosen people. In particular of the wretched and the poor, but especially of the poorest of the poor, namely the orphan and the widow.

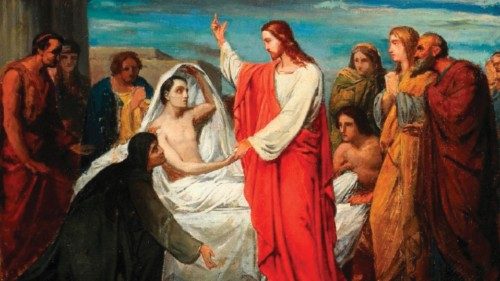

There are two widows who refer to each other between the New and Old Testament because their condition of absolute destitution due to having lost their husbands was aggravated by a further loss, that of their only son. Having lost all support, they experienced the most unjust sorrow. Today, widowhood may not always entail a state of utter destitution, but the pain of mothers who have lost a child is absolute. In both biblical accounts, God’s visitation through his prophet performs the miracle: to the widow of Sarepta of Sidon, the prophet Elijah returns her son (2 Kings 17:17-24) and Jesus does the same with the widow of Nain of Galilee (Luke 7:11-17). Why is it that at the end of both stories, everyone extols the two prophets and no one raises their voice against the scandal of a God who lets people believe that he is able to perform the greatest, yet the most just of miracles, and who has instead left countless widowed mothers in sorrow?

The people of the time knew very well that in these tales of resurrection, the emphasis does not fall on the impossible realism of the miracle. Instead, it is the prophet, that is, on the one who restores life because he is able to show what destitution and pain no longer allow one to see: the time of God's merciful compassion will come. “I know that my Go’el is alive,” cries Job, the one who has experienced the violence of poverty and pain to the full. Like him, the two widows are the symbol of all those who know how to wait for God's visit and know how to recognise his prophets. For it is they who speak of the God of the Magnificat and the Beatitudes, a God who “he has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent empty away.” (Lk 1:53) and who has promised the blessedness of consolation to “those who mourn” (Mt 5:4).

By MARINELLA PERRONI

Biblical scholar, Athenaeum Saint Anselm

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti