Kenya

In the urgency of the battle to save her land from the devastating effects of climate change, Kenyan activist Wanjira Maathai has realised that the dimension to be favoured is concreteness. What can be done now, should be done now, immediately. Especially if the solution is the one suggested by the people who experience the consequences of environmental disruption every day. Like the concrete sand dams experimented with by farmers in Kenya, which contain river water in dry seasons. Another example, the international cooperation in the South American region of Gran Chaco, which includes parts of Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina. This network is promoted by women’s associations, farmers and local institutions and has succeeded in creating a system capable of sounding the alarm on the arrival of the Pilcomayo river floods. These events are becoming more disastrous every year, and their aim is to give the possibility to contain the damage and save money on reconstruction.

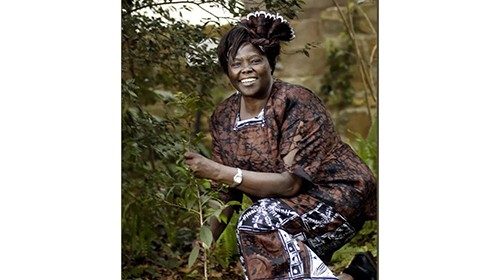

Pragmatism is one of the many qualities she learned from her mother Wanjara Maathai, who in 2004 was the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for her commitment to sustainable development. Wanjara Maathai died in 2011, but set an example in the 1970s by founding the Green Belt Movement that led to the planting of 50 million trees in Kenya alone. “In my own small way, I plant trees”, she said, signifying the need to start from one’s daily life. That phrase became one of her most famous mottos.

Wanjira was still a child when she accompanied her mother to the first actions of the movement; together they dug holes and then planted shrubs that produced colorful flowers. Her mother Wanjara explained to her that it was not only about the beauty of the landscape, because the gesture was also meant to give back to mothers the power to ensure a future for their children. “It is women who physically plant the trees precisely to claim the ability to manage what they have, namely the natural environment, which also means food for their family”, explains Wanjira now, for whom even today it is women who take the loving care of what surrounds human beings on their shoulders.

Despite such a significant role model to live up to, Wanjira Maathai has clearly found her role, stating, “I do not live in my mother’s shadow, I bathe in her light”. Today, she is president of the Foundation dedicated to Wanjara Maathai, and has now become regional vice-president of the World Resources Institute, a research organisation based in Nairobi that works with governments, companies and institutions to find best practices to tackle climate change. The climatic changes underway affect the poorest African regions and they are leading to serious phenomena such as hurricanes, floods, droughts and famine. Due to solely the lack of water, the number of malnourished sub-Saharans has risen by 50 per cent in recent years, while Mozambique and Zimbabwe are among the world’s most devastated Countries due to global warming, where seven out of ten people risk losing everything. There is very little time left to act.

Not surprisingly, one of the WRI’s initiatives is the reforestation and restoration of 100 million hectares of degraded and despoiled land in 30 African Countries through the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative. Wanjari lets the facts speak for themselves, but is not sparing with criticism of the ‘Western establishment’. In this, too, she resembles her mother, who in the 1970s was not afraid to take to the streets to demand more democracy and was not afraid of being arrested. Today, the arena is the digital one. “Europe and the United States should stop setting aside money to assist Countries damaged by climate change and start proposing actions instead”, she wrote for the Thomson Reuters agency. The actions are what the activist calls “local solutions” decided upon and led by communities that know their own territory better than anyone else.

For example, the Clean Cooking Alliance, of which Wanjira Maathai is a protagonist on the African continent, promotes the use of renewable energies to the kitchens of the poorest families, where kerosene, charcoal and wood burning release pollution and toxic gases. There is no more room for theory, the revolution has already begun.

“We need to increase climate resilience”, insists Wanjira Maathai, “and so we need to recognise the value of the experience of people living through these changes, give voice to their priorities, coordinate local institutions and international donors, and support these same communities economically. The need to channel western investment to stave off the danger of planetary apocalypse brings Wanjira Maathai closer to the voices of young people like Vanessa Nakate, Greta Thunberg and Sheela Patel, for whom the planet is witnessing a new divide between North and South, rich and less rich Countries. They call it climate injustice, to which strong governments turn a deaf ear. Responding to a tweet by UN Secretary General Anton Guterres, for whom the world’s population is clamoring for a change of pace on the climate while the powerful seem preoccupied with something else, Maathai writes in fiery terms, “The assault on the planet continues unabated. How will we nail those responsible for their misdeeds? We lack a system that punishes those responsible”. Overturning this power and curbing environmental crimes is, once again, primarily the task of women, the first to suffer environmental degradation, the first to realise that the earth is not only a mother but also a daughter to be cared for. “It is not an ethical question”, Wanjira Maathai clarifies, “we do not want to involve women just because it is right, but we have data and evidence that clearly say that if women act first-hand by making decisions, this will have a positive effect on the preservation of the planet”.

As children grow up alongside mothers, the Foundation that promotes Wanjara Maathai’s teaching is teeming with schoolchildren and young people who are taken on field trips to the forest so that they can feel, first with their senses than with their intellect, the goodness of a connection with nature. The most active ones sit on the board of directors, speak at conferences and soon learn to intertwine their environmental experience with their political commitment without discounting anyone. Time is so short.

by Laura Eduati

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti