Colombia

Four years ago, at the Goldman Prize ceremony, the highest award for environmental activists, Francia Márquez described herself as “part of a process”. Specifically, “of those women who employ maternal love to care for the earth as a living space. Of those who raise their voices to stop the destruction of rivers, forests, lakes”.

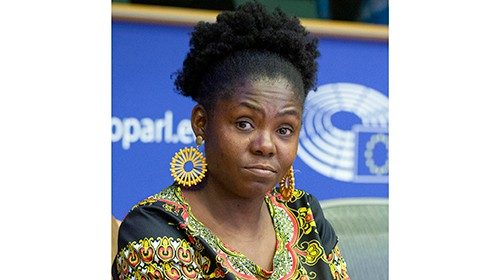

Throughout her life she has raised her voice in defence of the Earth, and risked her own; a 40-year-old Afro-Colombian, born in a floorless shack in the remote village of La Toma, Cauca, and a single mother forced to work as a maid to support her two children and pay for her Law studies.

Francia Marquez knew the courage of the “nobodies”, los nadie, who are men, and above all, women relegated to the margins by a system that excludes over 40 per cent of the national population. A force as invisible as it is indomitable. The same one that had led her, in 2014, to walk 130 kilometers, all the way to Bogotá, to denounce the pollution produced by legal and illegal mining in her region. The march convinced the government to start a dialogue. However, it turned Francia into an exile for she had to leave her community to escape the death threats. It happens often in Colombia, the deadliest Country for ecologists, with an average of one human rights defender murdered every two days. Yet few give up.

Like France Marquez, who has combined her commitment to the common home with political militancy. A few months ago, she was elected to the vice-presidency of the Country; the first black woman in national history. Her campaign slogan was “I am, because we are” to emphasise, once again, that she is part of a process of resistance that unites the history of los nadie. In particular, las nadie, the poor and minority women of the exterminated rural Colombia in the front line of the battle for vivir sabroso, the national version of buen vivir. A Latin American word that implies the recognition of the rights of human beings as much as of territory and communities. In addition, it presupposes that a fragile peace, which began in 2016, with an agreement between the government and the guerrillas of the Fuerzas armadas revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) is still a possibility.

One of the key points of the text is agrarian reform to give peasants access to land, one of the roots of the decades-long conflict. The knot is still unresolved due to the opposition of ‘latifundistas’, large national and multinational companies, and criminal groups that do not want to lose the coca plantations. There is a web of interests that fuels the violence. In 2021 - the fifth since peace - there have been at least 162 environmental conflicts in the Country. More than half of the 168 activists killed in the same year were small farmers and environmentalists. Women were a third of the total. (lucia capuzzi )

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti