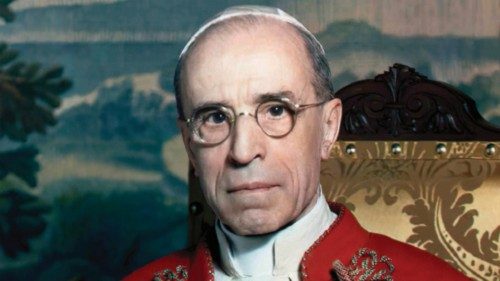

The opening of the archives on the pontificate of Pope Pius XII has launched a new season of studies that will hopefully prove fruitful and stimulating. Leading the way were Johan Ickx’s volume on Pius XII and the Jews, and Il Diario di un Cardinale edited by Sergio Pagano and dedicated to Pius XII’s Secretary of State, Cardinal Maglione. Cesare Catananti’s study entitled Il Vaticano nella Tormenta offers a perspective on wartime events experienced by the Papal Gendarmerie.

Now the new book by David I. Kertzer, “The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler”, attempts to offer a further contribution to the still-meager historiography budding from the newly-opened Vatican archives.

Long-awaited and heralded, Kertzer’s study seeks to cover the events that enveloped the pontificate of Pius XII. Indeed, according to the author’s preface, this book would be “the first full account with previously unknown materials and new revelations” on the choices Pius XII made between 1939 and 1945. However, the scholar does not quote the aforementioned volume by Ickx, neither in the text nor in the bibliography, a failure copied by the book by Catananti.

Kertzer’s “statement of intent” represents an extensive duty owed to readers. He rightly warns the author that the Vatican archives must be compared to other sources. And this makes his “moral contract” with readers all the more demanding.

Since we have already addressed some of the issues raised by Kertzer shortly after the opening of the archive on Pius XII (cf. Osservatore Romano of Sept. 4, 2020), and on the website vaticanfiles.net, we will limit our analysis to those aspects of this new book that we feel deserve critical scrutiny.

One of the “novelties” in Kertzer’s book would be a sort of “secret negotiation” with Hitler, ardently desired by Pius XII, carried out through highly confidential initiatives aimed at smoothing bilateral relations between the Holy See and Nazi Germany. This attempt would have been carried out between the end of 1939 and March 1940 (when the German foreign minister visited the Vatican). The protagonists of this “secret mission” included: the Prince of Hessen, a nobleman who had married Princess Mafalda of Savoy, and who was a known emissary of Hitler to Mussolini; Cardinal Camerlengo Lorenzo Lauri; and the representative of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Berlin, Raffaele Travaglini.

In the first volume of the official Vatican series Actes et Documents du Saint-Siège rélatifs à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, published as far back as 1965 (updated five years later), we read that “these secret negotiations did in fact exist; they were the preliminaries of Ribbentrop’s visit to Italy”. Further on in the same volume, on the date of March 9, 1940, we read, “On Monday the 11th, von Ribbentrop will visit the Holy Father. The audience has been secretly prepared for quite some time. Through the Prince of Hessen (I think) and by means of X”. The author of this note is Msgr. Domenico Tardini, Secretary for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs of the Secretariat of State. The “Mr. X” is none other than Viscount Raffaele Travaglini di Santa Rita, Marquis of Vergante. When the first volume of the Actes was published, Travaglini was still living (he would die on February 9, 1994). Because of the delicacy of the high offices he held in the immediate postwar period, Travaglini probably asked not to be mentioned in a volume that featured him in a negotiation with Nazi Germany. We know his name from Tardini’s original note, accessible as of March 2, 2020, in which the Monsignor identifies the protagonists of the operation as the “Prince of Hesse (I think) and Travaglini (for sure)”. But Travaglini is not unknown to historians. “A protégé of Cardinal Lauri [...], Travaglini is an ambassador of the Order of the Knights of Malta and travels to Berlin about twice a year, where he is also said to have negotiated repeatedly with Göring. One of Travaglini’s tasks was to improve relations between Italy, Germany and the Vatican”. This is the profile the Nazi security service made of him, in a document opened to scholars a long time ago.

So, there is nothing new here. Instead, there is ample evidence of the secret negotiation that Kertzer believes was “erased from all the official papers of the Holy See” as early as 1965, at the release of the first volume of Vatican documents that Paul VI ordered to be published. But there is more.

Kertzer believes he has overwhelming evidence of Pius XII’s desire to come to an agreement with Hitler. But what Kertzer sees as an embrassons-nous operation between Pius XII and Hitler is something very different. First, the documents on the case are found in the dossier of Ribbentrop’s visit to Rome, thus in the ordinary papal diplomatic bureaucracy, and not among Pius XII’s most secret papers. This is a clear sign that the “Travaglini-Hessen” operation was well known to the Pope’s collaborators. It also emerges that it was Hitler, not Pius XII, who ardently desired a new agreement in a broader sense than the 1933 Concordat. And this agreement was nothing but the revision of the Concordat of 1933 to include Austria (German after the Anschluss), Bohemia and Moravia (German protectorates after March 15, 1939). That we talk only about a revision of the Reichskonkordat of 1933 emerges from the fact that Hitler proposed to involve in the operation the authorities of Baden and Bavaria (Länder with which the Vatican had negotiated separate concordats in the pre-Nazi era). But Pacelli (Pope Pius XII’s birth surname), who knew those concordats from having negotiated them, was not the kind of man to give them up and therefore did not want to make any written commitments. Secondly, no negotiations would ever open before five papal conditions were accepted by Hitler. These conditions (Aufzeichnungen) are faithfully recorded in the Vatican archives, and were prepared personally by the Pope, who added to them the necessity of having a papal envoy in occupied Poland.

The conditions set by Pius XII pertained to the inalienable freedom of the Church in Germany; conditions that Hitler was obviously not ready to accept. On the German side it was also asked whether the papal note could “be considered a basis for an armistice” (a sign of a lingering “war” between the Third Reich and the Catholic Church); it also asked to “suppress for tactical and party reasons” the second part of the first point (concerning the withdrawal of publications particularly offensive to the Pope and the Church). Not only that; but the Prince of Hesse did not rule out adjusting “especially the fourth part” of the papal note (“to restore the freedom of the Church to defend itself openly against public attacks on Catholic doctrine and institutions”). They were obviously unacceptable conditions for the Pope. On the other hand, Hitler (busy on other fronts) had no concrete proposals of any kind. Ribbentrop’s March 1940 visit (which, moreover, forced the German delegation to remove swastikas from the motorcade admitted to the Vatican) was thus a failure and a disappointment. A new concordat should have crowned the expectations of the Prince of Hessen and Travaglini; instead, it was dismissed as one of many proposals for conciliation, official and unofficial, between Church and German state.

But if Hitler was thinking about a new Concordat, this means that the 1933 Concordat did not satisfy him. Kertzer does not clarify this point. He writes that the Concordat of 1933 “was a great triumph for Hitler”, and that, with Pacelli on the Papal Throne, Nazism now “could boast of recognition by the pope himself”.

But, if this is the case, why did Hitler want a new Concordat? Just because he had annexed more territories? This, Kertzer does not explain. Nor does he explain why the 1933 Concordat, going through political and ecclesial vicissitudes almost ninety years long, has survived and is still in force today, governing the relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Holy See.

Kertzer’s volume then presents some problems in source control. One example concerns Pius XII’s first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus dedicated to the tragedy of Poland invaded by Germany and the USSR. Kertzer dismisses the papal document as a set of pretty words harmless to Italy and Germany. But the sources tell a different story. Summi Pontificatus even entered into the work of the League of Nations. The encyclical was mentioned at the very session of the Council that decreed the expulsion of the USSR from the League of Nations for its unprovoked attack on Finland. It was on that occasion that the Council chairman, unbeknownst to those present, quoted Pius XII’s first encyclical. Having finished reading it, he said, “Gentlemen, the text that I have now read is the excerpt from the Encyclical Summi Pontificatus”. The reaction of those present at the Council’s session was of deepest emotion. The French delegate to the League of Nations, Paul-Boncour, greatly appreciated “such just and moving words”. The British delegate Butler joined in his French colleague’s moved comments. The Summi Pontificatus, so the Vatican papers say, produced “a great impression not only in League of Nations circles but also outside”. Positive indeed were the reactions in Paris and London. As a journalist in Geneva ironically noted, the Vatican entered the League of Nations on the same day the USSR was expelled from it.

But did Pius XII’s encyclical Summi Pontificatus appeal to the Germans? As much as the counselor of the German embassy in the Vatican, Menshausen, said that in his country the encyclical had been “read in the churches and that the newspapers spoke of it with respect”, the reality was quite different. German archives tell us that the Berlin authorities forbade the printing and distribution of the Summi Pontificatus (according to a telegram from Ernst Woermann to von Bergen, dated Nov. 8, 1939). Vatican sources even reveal to us that the Nazi Governorate in Poland disseminated an adulterated version of the encyclical, substituting the word “Germany” for the word “Poland”, and altering the Pope’s words of piety toward Poles to show that they were instead addressed to Germans.

A more correct use of sources then reveals the true German reactions to the Summi Pontificatus. Kertzer informs us that on Jan. 1, 1940, the German embassy counselor to the Vatican, Fritz Menshausen, wrote that the Pope had explained “that his speeches were logically general in nature and that he had specially drafted them so that they could not be interpreted by Germany as directed against it”. What Kertzer does not say is that Menshausen’s direct superior, Ambassador to the Vatican von Bergen, did everything he could to present it as a harmless document. But to no avail. “The relatively favorable judgment on the papal encyclical, in the report that has reached us, is not shared here”, Woermann wrote to him from Berlin. “Here one is of the opinion that with this encyclical, which is essentially a condemnation of the principle of the totalitarian state, the Pope has first and foremost kept in mind the Third Reich”. Not differently commented Woermann’s superior, von Weizsäcker: “If the Vatican”, he wrote to Bergen on Jan. 25, 1940, “asserts that these statements are of a general nature and not directed against anyone in particular, this is in our opinion true only in a formal sense. The Vatican adopts general phrases, but it is quite clear that it alludes to particular cases”. In the words of the head of the Reich’s High Security Office, Reinhard Heydrich, “the encyclical is directed solely against Germany, on the ideological level as well as with regard to the German-Polish conflict”. And he continued, “I consider it superfluous to emphasize how dangerous it is both internally and in foreign relations”. Nor can we overlook the words of the commander of the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller: “I have orders not to prohibit the reading of the Encyclical, but to prevent any dissemination of it, especially by leaflets”. These documents, being coeval with the aforementioned “secret negotiations” between Germany and the Holy See, help to further diminish its importance.

The themes we have just recalled are not found in Kertzer’s book. This is why the volume seems to betray an inaccurate checking of sources. For example, many documents that Kertzer cites as his archival findings were published as early as the 1970s-1980s. Moreover, opinions of various diplomats are often taken as fool’s gold, when in fact they are nothing more than personal views, if one compares the documents the right way. Kertzer then holds to the worn-out view that Pius XII cared only about baptized Jews. The “Ebrei” Series, opened on March 2, 2020 at the behest of Pope Francis, seems to us to have done justice to this fusty cliché.

But what we consider a truly serious omission concerns the October 16, 1943 roundup of Roman Jews. Kertzer follows Cardinal Maglione’s record when he narrates his conversation with the German ambassador. But then he omits some decisive words addressed by the Cardinal to von Weizsäcker (new ambassador to the Vatican): “The Holy See must not be put in the need to protest. Should the Holy See be obliged to do so, it would rely, for the consequences, on Divine Providence”. In other words, if the raid of the Roman Jews continued by Hitler’s supreme order, the Holy See would protest by accepting to suffer the appropriate consequences. This omission on the part of Kertzer is no minor affair.

This omission is then compounded by a failure to compare with British sources. Here follows the notes sent to London by British representative in the Vatican, Osborne, on Oct. 31, 1943: “As soon as he heard of the arrests of Jews in Rome Cardinal Secretary of State sent for the German Ambassador and formulated some [sort?] of protest”, achieving the desired result. And how to overlook, for the humanitarian aspects of that tragic “Black Saturday”, the diary of the Slovak minister in the Vatican, Karol Sidor? “On the Holy Father’s orders”, reads the document made known by scholars Róbert Letz and Peter Slepčan, “more than a hundred Jews and Italian officials were hidden in the Generalate of the Jesuits. Likewise in every convent Jews with their entire families are hidden”.

Still on the subject of “Black Saturday” in Rome, Kertzer’s volume presents further problems and even a rather serious error. Kertzer informs us that on October 18, 1943, British minister Osborne was received in audience by Pius XII, who expressed to him his concerns about food shortages and possible unrest in Rome. The Pope added that he had no reason to complain about the Germans, who were respecting the Vatican’s neutrality. “Oddly”, Kertzer writes, “Osborne makes only indirect reference to the roundup of Rome’s Jews in his report of his audience to London”. This is true. But on October 31, 1943 Osborne sent the dispatch we mentioned above — and unknown to Kertzer.

The serious mistake made by the scholar concerns instead the American delegate to Pius XII, Harold Tittmann. Kertzer writes that, as in the audience with Osborne, “apparently, the pope made no mention of what had happened to Rome’s Jews in his meetings with the two envoys, or, if he did, it was regarded as too inconsequential for them to put in their reports”. Kertzer places the papal audience with Tittmann on October 19, 1943. In reality, it happened on the 14th (at 11 a.m.), which is two days before, not three days after the raid on the Rome Ghetto. We are told this by the audience sheets for 1943 kept in the Master of the Chamber’s files which, on the contrary, do not record any audience granted by the Pope to Tittmann on October 19, 1943. The dating error, we clarified long ago, is due to the fact that Tittmann had no telegraph and cipher service, and therefore had to rely on his English colleague Osborne. The date of October 19, 1943 is in fact that of the telegram with which Osborne “refiled” Tittmann’s undated dispatch, of which, moreover, two versions exist. In the one preserved in the British archives Tittmann writes that he had not seen the Pope since the previous Monday (19th October was Monday — can Tittmann ever have had two audiences with Pius XII on two consecutive days?). In the copy of the telegram preserved in American archives we read that he had not seen the Pope since the previous year. There are evidently transmission errors due to the difficult passages Tittmann’s dispatch underwent before reaching its destination via Algiers, in a complicated interplay (Osborne’s dispatch of October 19, 1943 contains Tittmann’s undated one; and a later Foreign Office dispatch for the British Embassy in Washington contains both). On October 15, 1943, the Osservatore Romano gave timely notice of the papal audience with Tittmann. Only by “creative historiography” could one therefore accuse Pius XII of keeping silent on October 14, 1943, about an event that occurred in the Rome Ghetto two days later.

Unsatisfactory use of sources and various other problems (omissions and a sometimes inaccurate critical method) do not, therefore, make this volume, moreover written in fluent fictional prose, the definitive Thule of research on Pius XII. This is, moreover, normal for the immense amount of documents which, made accessible by the Vatican at the height of the pandemic, will only now and gradually be the subject of hopefully more accomplished analysis.

By Matteo Luigi Napolitano

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti