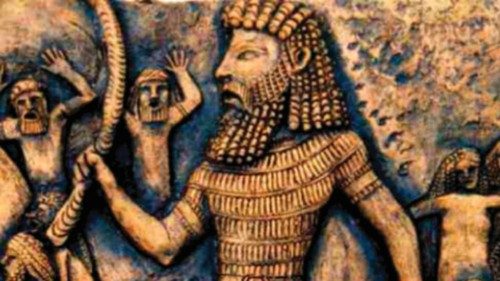

What makes some stories universal across language, culture, and time? Most formulas fall to pieces upon examination, though as his Holiness Pope Francis pointed out in his message for World Communications day, it’s significant that the Latin word ‘texere,’ to weave, is the root word not only for “textile” but “text.” Eastern cultures also employ the metaphor of cloth to lend visible texture and form to the idea of story: the essential texts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism are known as sutras, ‘sutra’ being a word for thread that gives us the English “suture,” and ‘tantra,’ a Sanskrit word literally meaning “loom”, being a system of weaving the diverse threads of the sutras into a comprehensive whole. Once we look, the metaphors are everywhere: we speak of spinning a tale, of piecing together a story, of losing the thread, of embroidering the truth, of fabricating an alibi, of unraveling a falsehood, of a tissue of lies. In American idiom stories are sometimes “yarns”; Grandmother Spider, in the stories of the Native Americans, was the tiny figure who literally wove the world into existence; and of course the ancient Greeks saw mortal, individual life itself as a thread being spun by the Fates, to be cut unpredictably we know not when. Throughout life we wrap ourselves in the fabric of story to protect ourselves, to clothe our brides, to swaddle our babies, to bandage our wounds, to comfort our grieving, to shroud our dead. And from Gilgamesh onward, story has helped humanity to find design in the larger fabric stretching far beyond individual existence. By tracing “the figure in the carpet” as Henry James calls it, following the design close at hand into the larger pattern of voices and geographies extending beyond our own, we can understand our place in history and internalize concepts that otherwise might require a lifetime of experience, study, and observation to grasp. The stories we tell and re-tell and pass down to one other are tents to gather under, flags to follow into battle, unbreakable cords to connect the living and the dead, and the interweaving of these vast textiles across centuries and cultures binds us powerfully to each other and to history, guiding us through the generations.

Perhaps most pertinently though, stories are sailcloths that we hoist to catch a breath of the divine. The thoughts of other people assume a curious life in us, which is why literature is the most spiritual of all the arts and certainly the most transformative. Like no other mode of communication, a story can change the way we think, whether for good or for ill, and the right story at the right time is a mainsail that can storm us powerfully into unpiloted waters, shifting us quickly and sometimes permanently from one place to another — sometimes to rich and active coastlines we never knew were on the map. Cultures ancient and modern have always regarded story as magical —and dangerous — for this reason: because it’s possible to hear a story and at the end of the story to be literally a different person. Plato, the great storyteller, warns us urgently and repeatedly of the disastrous harm the wrong stories can inflict, particularly upon the young, while at the same time having Socrates resort continually to story while trying to convey a difficult metaphysical point. And of course when Christ wants to shake his disciples from complacency or is having a hard time making them understand a complex truth about forgiveness, say, or love, He always moves from the abstract and conceptual to the lamb, the water jar, the fig tree, to the house of many mansions and the wedding feast.

Some stories are corrosive. Others ensnare us in false arguments, allure us with degrading gossip, or sow discord and lies. (It’s interesting that “net” and “web,” old English words for meshworks meant to entangle and bring down prey, are also the two words we use for the Internet.) Yet overwhelmingly, though by no means universally, the truths we find in great works of fiction are spiritual, as to imagine ourselves deeply into the lives of others is itself a spiritual task. To be a writer of fiction or even a serious reader of fiction is to understand that only by the imagination can one arrive at certain intimate and complex truths. If as in the works of Faulkner, Camus or Beckett, we never arrive at full religious sensibility, nonetheless we have serious grappling with questions of being and morality, as well as rich spluttering immersion in the mystery of what it is to be a human in the world. As Thomas Merton, in 1958, wrote to Boris Pasternak, the author of Dr. Zhivago:

I do not insist on this division between spirituality and art, for I think that even things that are not patently spiritual if they come from the heart of a spiritual person are spiritual.

Or, as Pope Francis has said: “Every human story is, in a certain sense, a divine story.” The best stories are truthful: even fairy stories like the tales of Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen are receptacles of a certain kind of truth, while even popular fictions are able to bestow a complex and detailed grasp of experiential abstractions played out on the field of time, understandings difficult to obtain any other way. On one level: an early novel like Robinson Crusoe was enthralling — an alternate life, almost — to readers of the early 1770s who mostly lived and died without venturing more than fifty miles from home, in an era before film or photography, most of whom had never seen the ocean and who had certainly never laid eyes upon a sea tortoise or been shipwrecked upon a desert isle. On quite another: while operating on multiple complex planes, and without necessarily setting out to do so, a novel like Crime and Punishment helps us to know at first hand the knotty, convoluted, and far-reaching repercussions of murder — even the murder of a supposedly worthless person — beyond the obvious danger of retribution from civil law. The Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector, in her final novel The Hour of the Star, asks: “Who hasn’t wondered: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” In some respects, the entirety of Crime and Punishment is a 450 page response to this question. But to be plunged — head-first and thrashing — into the delirium of Raskolnikov’s guilt and redemption is also to see that other, deeper laws are at play, far beyond the temporal reach of the Petersburg police force.

Goethe puts forward the idea of story-as-textile by his metaphor of the scarlet thread, which he explains by speaking of a custom of the British navy: “The ropes in use in the royal navy, from the largest to the smallest, are so twisted that a red thread runs through them from end to end, which cannot be extracted without undoing the whole, and by which the smallest pieces may be recognized as belonging to the crown.” Red — the ancient color of kingdoms and princes — is of course also the color of Christ’s sacrifice, a scarlet flash winding from this troubled winter of 2021 all the way back to the Crown of Thorns, binding heart to heart and connecting the mortal to the divine. Like the scarlet cord of the Canaanite Rahab — signifying her faith to the God of Israel — it is a sign of covenant and protection. It is the thread which, in the words of G.K. Chesterton, is long enough to let the sinner wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a single twitch. And as with the ball of red thread that Ariadne gives Theseus as he goes into the labyrinth, it’s a thread that promises to show a path to safety.

Thinkers from Aristotle onward have tried to break down story to its irreducible elements, though no single definition I’ve read encompasses the whole range of story, from folktale to comics to Chekhov to big fashionable films of the moment. Certainly mystery, in its very broadest sense of an unanswered question, is a thread that draws us in and keeps us going in story of all types, right down to anecdotes we exchange at the grocery. Something’s happened: we want to know what. μυστήριονMysterion, means literally in Classical Greek “a hidden thing. The opening of Inferno — famous to the point that we’ve almost stopped being able to hear it — opens up and blooms again when we think of it as a tiny object lesson in the nature of mystery, in only three lines:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

Ché la diritta via era smarrita

In the middle of my life’s journey

I woke to find myself in a dark wood

Where the true path was lost.

Everything here is mystery; everything makes us want to know more. What’s around us in that dark wood, anyway? How did we get there? How do we get out? Are we quite as alone as we seem to be? How can we find the help we need? Mystery — that enticing trail running away into the dark — is the thread that pulls us forward in all stories mundane to sublime, from police procedural to Shakespeare. And of course mystery is also a component of religious faith, leading us on and compelling us to follow, always with the hope of some kind of reward or deeper understanding at the end. Joyful, sorrowful, glorious: all the great stories of Christianity contain some strong element of mystery, and their principles are to be found not only on the grandest supernatural level but the most humble: stories of gifts received, of generosity and loyalty and courage rewarded, of outcasts brought in and cared for, and evil ending where it must. Of suffering borne alone but also of blessing bestowed unexpectedly, help from unseen quarters. Reunion after separation. The cry for mercy being answered.

There’s also the question of grace. It’s true that the most successful stories end with some kind of subtle shift, or surprise, even if it’s as small as a change in the weather — and isn’t grace (or “epiphany” as Joyce calls it) itself a sort of surprise? We can’t predict grace; it beams on us unpredictably and often from quite unexpected angles. It happens when we ask for it and sometimes when we don’t. It is the moment that slips up quietly from behind and takes us by the elbow and whispers: Look!

And sometimes all we can do is watch for it, and wait. I’m writing these words in January of 2021, at the beginning of a new year and the ending of another which will be remembered, in America and around the world, as a wasp’s nest of pain, fakery, and loss. But it’s good to remember that grace — in life as in fiction — is often a gift we don’t see coming. And if stories can open the possibility of living in a deeper, more connected and empathetic way, they can also help us remember that we live in a world in which grace, at least, is possible.

Donna Tartt

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti