Margery, who talks

The experience of the English mystic in the fifteenth century

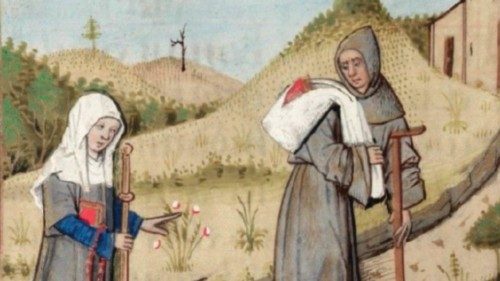

In the early 1400s, a group of pilgrims paused for thirteen weeks in Venice before embarking for Jerusalem. Among the travelers, there was an English woman who claimed to speak with Jesus every day, and to have received a vision ordering her to dress in white like cloistered nuns. However, being the mother of fourteen children, she could not claim virginal purity.

Her name was Margery Kempe, who was legally married and just turned forty, but her manifestations of faith had caused her to be accused of heresy in England, and receive the reproach of priests and bishops, and even a brief spell of imprisonment. Now that she has embarked alone on a long holy journey that will take her to Rome, Assisi, Santiago de Compostela, the Holy Land, Holland and Norway, the persecutions continue. For example, her Venetian traveling companions, who had become annoyed by her mysticism, banish her from the hostel’s communal canteen, because during meals she constantly speaks of Christ’s miracle and weeps profusely when she prays.

A similar hardship had happened on the previous stage, in Constance, Germany, where the pilgrims with whom she was traveling had even cut off her skirt and forced her to walk around dressed in just a jute sack. In Bologna, one of the pilgrims offered her a hand of mercy, saying “If you want to continue to stay with us, we must come to an agreement: you must not talk about the Gospel when we are in your presence, and you will have to remain seated and cheerful as we do during lunch and dinner”. It is the Margery herself who recounts these episodes in her Book of Margery Kempe, the first autobiography in English. The book, dictated to a scribe because she was illiterate, documents her journey in generous with priceless details. For example, the story, while in Venice, of the chartering of a commercial ship bound for Jerusalem with beds rented to pilgrims for whom there were also barrels of wine to make the crossing less austere. However, even on this leg of her journey, Kempe was mocked and marginalized.

In fact, her presence acts as a revelation of others’ souls. The people who experience faith as a cloak of social formality mock her, while the pure of heart, the poor and the marginalized welcome and support her. During her travels, the pilgrim often finds shelter in the homes of people who have nothing and of which only she has left a trace in her writing about them.

Kempe was born in 1373 just when her contemporary Geoffrey Chaucer began to compose the masterpiece The Canterbury Tales. His is the story of a group of pilgrims who walk the distance between London and the cathedral where the sacred remains of the Church martyr Thomas Becket are kept. At that time, pilgrimages were a living reality and occurred daily, and often for reasons unrelated to the depth of faith. After all, upon arrival in a sanctuary it was possible to buy indulgences for themselves and their loved ones with cash. It was also quite a common occurrence that women joined these holy journeys without an escort. In Chaucer’s volume – with which English literature is founded, there is the story of the extraordinary woman of Bath, who had been widowed five times, devoted to God in her own way, and who was travelling with a carnal and earthly hope of finding a new husband.

Margery Kempe, this woman’s peer, belonged to the same social stock; an entrepreneur and lover of expensive clothes, but then took the opposite path. She was born in King’s Lynn in the east of England, a daughter of a notable and married for twenty years to a rich bourgeoisie. After their first child was born, Kempe suffered from evil visions. She saw devils chasing her and committed acts of self-harm until one day she saw Jesus dressed in purple silk for the first time. The mystical dialogue continued everyday for forty years, and became a loving and supportive encounter. Kempe recounts that it was Jesus himself who at one point urged her to put aside motherhood and dedicate herself to a holy life.

The mystic and pilgrim went to Mass several times a day and indulged in uncontrollable crying even while on her way. In Rome, while wandering in a working-class neighborhood, she took children from their mothers’ arms and kissed them, convinced that they were the incarnation of Christ.

These are the signs of that affective piety that had taken hold in the early Middle Ages; however, they caused Margery Kempe great strife. This was still more than a century before the Anglican schism, but in English society, there was a growing impatience with a Church that was considered distant. This was when the Lollard movement was founded which would then be bloodily repressed. The mayor of King’s Lynn accused her of Lollardism in public because she dared to claim a direct dialogue with God, without the mediation of priests. Kempe responded to the annoyance of her fellow citizens and pilgrims with the strength of her faith, “I’m sorry but I must speak to my Lord Jesus Christ despite the world forbidding me to do so”.

She understood it deeply. Her husband John Kempe, of whom the book preserves the portrait of a man who for love of his wife, albeit with some reluctance, embraced chastity. He left her free to undertake a long pilgrimage in the footsteps of St Bridget of Sweden, she too a mystic and tireless pilgrim. St Bridget had been canonized in 1391 by Pope Boniface IX who was a spiritual example she mentions several times in her autobiography.

After months of travel, around 1414 Margery Kempe finally set foot in Jerusalem riding a donkey from which she risked falling “because she could hardly bear the sweetness and grace that God had embroidered in her heart”.

When she arrived on Mount Calvary, she recounted that she felt the suffering of Christ in her flesh “as if she could really see the body of Jesus suspended in front of her”. So great was the effect, that from that moment on “when she saw a crucifix, or a man or even a wounded animal, or if she saw a man beating a child or a beast with a whip, she always thought she saw the Lord beaten or wounded” and on those occasions her weeping reached paroxysm.

The Holy Sepulcher friars approached her with wonder. They had heard of a woman born in England who talked to God every day. After seeing the place of Christ’s burial, then the place where the apostles had received the message of the Resurrection, and after touching Lazarus’ tomb and visiting Bethany, where Mary and Martha lived, Margery Kempe received an order from God to return.

On the ship to Venice, her fellow passengers suffered and fell ill. Instead, she was comforted by Jesus’ words, “Do not be afraid, my daughter, no man will die in the ship where you are traveling.”

Upon landing in Italy, her fellow pilgrims abandoned her once again. Alone and mocked, Margery Kempe the pilgrim crossed the English Channel and landed in Dover where fortunately she received the help of a poor man who, sensing her holiness, accompanied her to Canterbury on horseback. Her faith is in fact strengthened day after day thanks to the constant presence of a compassionate God who found a way to help her along the way. Even though she was alone, Kempe was never actually alone thanks to God’s voice: “The greater the shame, the greater the spite and disapproval that you suffer because of me, the greater is my love for you”.

by Laura Eduati

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti