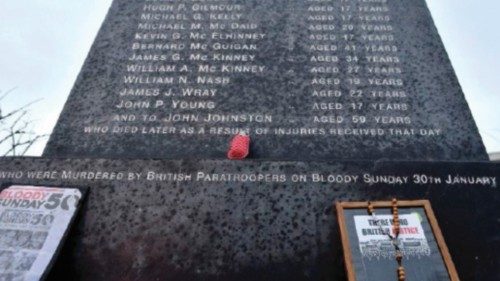

It has been 50 years since British soldiers killed 14 unarmed Catholic civil rights marchers in what has become known as “Bloody Sunday”. Family and friends of the 13 Catholics who died in the Bogside area of the City of Derry (Londonderry) on 30 January 1972 — and of a 14th who died later of his wounds — gathered this week for a series of commemorations to mark this tragic event. Among them, was a Mass celebrated by Bishop of Derry Donal McKeown to which his Anglican counterpart, Bishop Andrew Forster, was also invited. Speaking to Vatican News, Bishop McKeown expressed his closeness to the people affected: “I think about the dignity of many people, the courage of many people, the strength of many people who have come through this, particularly because of their faith background”.

The bloodshed in Northern Ireland lasted for decades after Bloody Sunday. It was not until April 1998 that the signing of the Good Friday peace agreement brought an end to the 30 years of conflict known as the “Troubles”, that caused 3,000 deaths. And it was only in 2010 that a judicial inquiry found that the victims of Bloody Sunday were innocent and had posed no threat to the military. Speaking about healing the wounds of the past, the Bishop of Derry noted that much work had been achieved in building a strong relationship between the Catholic and Protestant Churches. Indeed, he pointed out, “Church leaders were way ahead of politicians”.

Last year, the current British government announced a plan to halt all prosecutions of soldiers and militants in a bid to draw a line under the conflict, but families and friends of the victims have vowed they will not give up their call for prosecutions. Despite this, while acknowledging that there are still tensions behind Northern Ireland’s conflict, “the war is over”, said Bishop McKeown. In today’s Northern Ireland, “differences of opinion, differences of identity can be celebrated; not seen as something to be feared, and I hope that we as Church leaders can ensure that whatever direction the island takes, whatever direction Europe takes, it is a society that is able to process the pain of being human; process the pain of the past and build hope for the future”. He called on the faithful to “look at the past with compassion; to forgive and remember, and be able to move on because we deserve to be architects of the future and not prisoners of the past.” The future, he stressed, “belongs to those who can generate hope from the past rather than despair”.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti