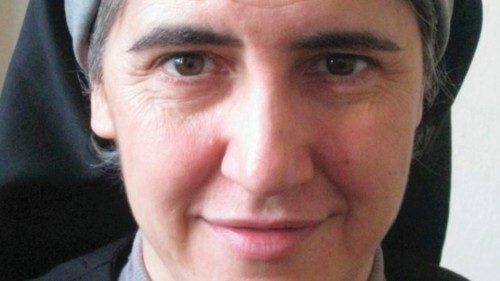

Teresa Forcades is a Benedictine nun, a feminist, a queer theologian, a mystic, an active voice calling for Catalan independence, a medical graduate, gay rights activist, writer of books about faith, the body, and the supporter of bold and controversial theses inside and outside the Church….there are indeed no shortage of conversation topics for our interview. When our encounter took place in a Benedictine monastery, nestled in those mountains of Montserrat that are the symbol of untamed Catalonia -a powerful and magical place where the scent of faith is mixed with that of freedom-, the temptation to let oneself go to the charm of listening and discussion is great. Moreover, Teresa Forcades, with her cheerfulness, her bold thinking, and her amiable words knows how to be fascinating. Her good humor is contagious. Her ability to find the underlying cause of issues without hesitation, to “stir things up”, to destroy clichés and stereotypes is unquestionable. However, we do not today. Let us not give in to the temptation to talk about everything. I prefer – I can tell you at the outset- to address just one issue with her, that of the relationship between women and the Church, of patriarchy in the ecclesiastical institution, of women who are still on the margins when not openly discriminated against, of the struggles being attempted to bring about change. “Of course, let’s talk about it”, she replies “but starting from a point that I care a lot about, that I want to emphasize, that is important and unspoken. Because the fact that the patriarchy is strong is obvious, so obvious, that it is not even worth pointing out. Who hasn’t figured that out?”

Instead, what is so far unsaid, and with which we should commence?

The Catholic Church, in which the patriarchy is strong, is, however, the institution that more than any other has preserved the presence, history and memory of women. If this is alive, if today we know what so many women in different places and times have done, felt, and thought, we owe it to Catholicism that every day and in every part of the world, it celebrates the name and remembers the works of one of them. I say the names of Clare, Hildegard, Teresa; I could give hundreds of others. Women have been there and are there. Not without conflict, of course. Nevertheless, it has happened and it has to be said so now. With emphasis, with conviction, with strength. I would add that not only have women been there and acted but also they have created communities and these are still alive today. In short, they have built their own history in the Church, a female history. This is difficult; we know it is difficult, very difficult not only in a Catholic institution. It is so in the world. When I graduated in medicine in 1990 I studied that two men, James Watson and Francis Crick had discovered the structure of DNA, which was an enormous scientific revelation that laid the foundations of modern molecular biology. Yet, only a few years ago I learned that the first to discover the structure of DNA had been a woman, Rosalind Franklin. It was as if who she was, and what she had discovered, had been erased. History did not understand her.

Are you telling me that the Catholic Church has built, has preserved a female presence and culture more than other religions?

I do not intend to be controversial. It may be my ignorance, but I ask you, in what culture, in what country, in what religion, where do we find female writings and works as they are in the Catholic Church?

Today, however, for many, change in the Church is slower, the resistance stronger than in other institutions. Why?

It is said that the Church is unprepared, that it still has work to do. Perhaps this is true. I believe, however, that if something is right, it must be done. Well, with thoughtfulness and with diplomacy, if necessary, but it must be done.

You are also known to be an advocate for female priestly ordination. Yet, the Holy See says the priesthood is reserved for men.

It is considered the issue of all issues today. It has also been discussed in the past, and it has been rejected. My opinion is that there are no theological obstacles in Scripture.

With Francis, is anything moving for women in the Church? If the answer is yes, what is it?

Francis gave women positions of responsibility in the Roman curia for the first time. For the first time, in some cases, they are in the organization chart of the Vatican curia in positions higher than some bishops are. To me, this seems a new and important fact.

Yet it seems that the word “feminism” still bothers not only for men but also for women in the Church. Can you explain why?

The Catholic Church is made up of women; in fact, women are a majority. So here, we experience a very strange situation. An institution, a reality by a very large percentage, in which seventy, eighty percent, are women count for little or nothing. No wonder that such a strange situation, such a singular situation causes anxiety, disquiet, uncertainty, and fear. The men of the Church know all too well that if women were to abandon it, it would simply cease to exist.

I want to tell you about a particular incident. One day, during a religious service, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, the American theologian, biblical scholar and feminist, asked the women to leave and gather outside the Church. With a symbolic gesture she wanted to show that without them, the priest remained alone. Exactly what happened and would happen in any church, in any religious service.

So has feminism been able to break in and undermine the patriarchy of the Church?

Not only that. Today we can speak of a feminist theology in history. We can speak of a feminism that does not define itself as such but that has been, is present and makes choices even in a society, an institution, a dominant thought that excludes women. I demonstrate this with simplicity. We denounce as a patriarchal system that in which women - even one of them - are excluded or discriminated against. Moreover, we can call feminist any action - of a woman or a man - that denounces this exclusion.

A theologian of the fourth century, Gregory of Nazianzus, observed, with regard to adultery, that if it was committed by a woman, the full weight of the law was unloaded on her and she was punished to the point of death; if it was committed by a man, there was no punishment. This is not right, he pointed out, because the Scriptures, the commandment says “honor your father and mother”. They call for the same behavior for men and women. Therefore, the laws applied to punish adultery - he deduced - are not the laws of God. This is a criticism of patriarchy, don’t you think? Nevertheless, Gregory of Nazianzus went further. He wondered why this happened, why it was possible. The reason lay in the fact - he explained - that men, not by women, had written the law. As you can see, the position of a fourth-century theologian was already critical of patriarchy. We can already speak of a feminist theology in history.

However, feminism for you, Teresa Forcades, what is it?

Answering this question is also simple. It does not take much to define it. It is three or four points. First, feminism means to identify discrimination. Not everyone sees it. Gregory in the fourth century saw it, others do not even today. Second, to become aware of the injustice of this discrimination. In short, take a clear stand against it. However, even this is not enough, we must raise up against discrimination we must act, fight to eliminate it. To carry out feminist theology there is a fourth point. It must be clear to us that discrimination does not come from nature, does not come from God, and does not come from the sacred texts. Therefore, it is necessary to criticize and reject the theology that theorizes discrimination because it believes God wants it.

In the Church and in Christianity, is there the strength to break down such profound discriminations as those that Francis himself denounces daily?

I think so. At other times, it has happened. Think about what marriage was before Christianity. An economic issue that involved property: whose property it was, and who was it to be bequeathed to. Not to mention, whose child it was. This presupposed the control and subordination of the woman. In the ancient world, marriage was a contract between two men, the father and the husband. For the Catholic Church, marriage is the loving encounter between a man and a woman who choose each other and unite. A radical change from the then dominant culture. Also in the Jewish tradition, after all, a woman is not the mother of the son of the man but “flesh of his flesh”.

If you were to make a suggestion to women who are uncomfortable in the Church and want to break the stalemate, what would you say?

I would not make generalized announcements. I do not have a program to suggest. I do know, however, from direct experience, that women must always ask themselves a question that they are not - we are not - used to asking: I, just me, what do I think? What is my deepest desire, what do I really want? What is right? The Church has an extraordinary history of feminine strength and resistance. We need to study it, value it, and tell it. There are women who ask themselves these questions every day, many who asked themselves them in the past. In my monastery the nuns came into conflict, there were barricades when after the Council of Trent the Church asked for a stricter enclosure for women.

May I conclude this conversation by saying that you are optimistic and hopeful that women will change the Church and that the Church will change because of women.

Feminism is said to have begun at the beginning of the century, with the demand for political rights. Then there was a second wave in the 1970s. The real beginning in my opinion is with the Seneca Falls convention in 1848 on women’s rights in the US. Women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton not only reiterated that the Bible had hitherto been interpreted in a patriarchal way and that this was not the true reading of the sacred texts, but they foresaw the political consequences. This had already happened with African American slaves. The slaves learned Christianity from their masters but then, when they learned to read, they realized that the true message of the Scriptures was not the one that was sent by their oppressors, that the Bible did not justify slavery and inequality. Something extraordinary happened then. Usually - we know - the oppressed reject the religion of the oppressor, instead many African American slaves remained faithful to Christianity but with a different reading of the Scriptures and accused their masters of not having read the Bible correctly. The same thing is happening for women. In faith and in the Scriptures there is all the strength to fight the patriarchy of the Church.

by Ritanna Armeni

TERESA FORCADES I VILA is a Benedictine nun at the Monastery of Montserrat. Born in Barcelona, 56 years ago, she is a doctor with a specialization in Internal Medicine from Buffalo (USA), a theologian with a master’s degree from Harvard, and a feminist and political activist. Raised in a non-believing family, she discovered her faith at the school of nuns where her parents had enrolled her. She read the Gospel for the first time at age 15. In 1995, before returning to the United States, she decided to spend a few weeks at the Montserrat Monastery to prepare for an important medical exam. It was there, in that monastery built on the mountain of Monistrol de Montserrat, a small town in the autonomous community of Catalonia, which is a symbol, and which is also an important pilgrimage site that she realized she wanted to become a nun. She has been a cloistered nun since 1997. In 2012 she founded the political movement “Procés Constituent” together with Arcadi Oliveres, a Spanish economist, academic and social activist, and president of “Justícia i Pau”, a Christian pacifist group. They propose to achieve Catalonia’s independence through a new political and social model based on self-organization and social mobilization. In 2015, as Catalonia’s regional elections approached, she received permission from her superior and the Holy See to leave the cloister for three years, and thus be able to enter the election campaign by running for president of the region. In 2018, she returned to the monastery to resume her life as a contemplative.

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti

Purchase the Encyclical here Fratelli Tutti